Now I can visualise the drama clearly. His bride was quite the loveliest creature we had ever seen. We were all so fair and she was dark. Our mother loved Isabella, and Caroline confided to me that she was sure our mother wished we were all like her. Perhaps she did, for Isabella was not only beautiful, she was very clever—which none of us was. But she had one other characteristic, which we lacked. She was melancholy. I might have been frivolous; I might have known little about books; but there was one thing I did know and that was how to enjoy life; and this was something which, for all her learning, was beyond Isabella’s powers. The only rime I ever saw her laugh was with our sister Maria Christina, who was a year younger than Joseph.

Isabella would go into the gardens when Maria Christina was there; they would walk together arm in arm, and then Isabella looked as nearly happy-as she ever could. I was glad that she liked one of us, but it was a pity it was not Joseph, for he had fallen deeply in love with her.

There was a great deal of excitement when she was going to have a baby; but when the child was born it was a weakling, and it did not live long. She had two children and they both died.

Caroline and I were too busy with our own affairs to think much about Joseph and his. I must have noticed that he looked very sad, always, and it certainly made some impression on me even then, because it comes back so clearly all these years later. What a dark tragedy that was! And there was I living under the same roof with it.

Isabella was constantly talking about death and how she longed for it.

That seemed strange to me. Death was something which happened to old people—or little babies whom one did not really know. It had little to do with us.

Caroline and I, hiding ourselves behind a clipped hedge in the gardens, once heard Isabella and Maria Christina talking together.

“What right have I in this world?” Isabella was saying.

“I am no good.

If it were not sinful I would kill myself. I should already have done so. “

Maria Christina laughed at her. Maria Christina was not the kindest of our sisters and on the rare occasions when she did notice us she would say something spiteful, so we avoided her.

“You suffer from a desire to seem heroic,” she retorted.

“It’s utter selfishness.”

Then she walked away and left Isabella looking after her, stricken.

I thought about that scene tor five whole minutes, which was a long rime for me.

And Isabella did die just as she had said she wanted to. She was in Vienna for only two years in all. Poor Joseph was heartbroken. He was constantly writing letters to Isa bella’s father in Parma and they were all about Isabella, how wonderful she had been, how there was no one like her.

I have lost everything,” he told my brother Leopold.

“My beloved wife my love … has gone. How can I survive this terrible separation?”

One day I saw Joseph with Maria Christina. Her eyes were Sashing with hatred and she was saying: “It’s true. I will show you her letters.

They will tell you all you want to know. You will see that I not you was the one she loved. “

It falls into place now. Poor Joseph! Poor Isabella! I understand why Isabella was so sad and wished for death, ashamed of her love and yet unable to suppress it; and Maria Christina, who would always want her revenge, had betrayed her to poor Joseph.

Immersed as I was then in my own affairs I saw this tragedy as through a misted glass, but because my own suffering has now made of me a different person from the careless creature I was in my youth, I understand so much and I have sympathy to give to others who suffer. I brood on their sufferings perhaps because I cannot bear to contemplate my own.

Joseph was very unhappy for a long time, but because he was the eldest and more important than any of us he must have a wife. He was so angry when a new wife was selected for him by our mother and Prince Wenzel Anton Kaunitz that when she arrived in Vienna he scarcely spoke to her. She was very different from Isabella, being small and fat, with brown uneven teeth and red spots on her face. Joseph told Leopold, in whom he used to confide more than in anyone else at our mother’s court, that he was wretched and he was not going to pretend to be anything else for it was not in his nature to pretend. Her name was Josepha and she must have been unhappy too, for he had a barrier built across the balcony on to which their separate rooms opened so that he would never meet her if she stepped from her room at the same time as he stepped from his.

Maria Christina said: “If I were Joseph’s wife, I’d go and hang myself on a tree in the Schonbrunn gardens.”

When I was ten years old I was aware of tragedy, which was real even to me because it concerned me deeply.

Leopold was going to be married. There was nothing very exciting to Caroline and me about this, because with so many brothers and sisters there were other weddings; and it was only one which was held in Vienna which would have interested us; but Leopold was being married in Innsbruck. < Father was going to the wedding, but Mother could not leave Vienna as her state duties kept her there, i I was in the schoolroom tracing a picture when one of my father’s pages came to say that my father wanted to say goodbye to me at once.

I was surprised because I had said goodbye to him half an hour earlier and I had seen him ride off with his attendants.

Aja was in a fluster.

“Something has happened,” she said.

“Go at once.”

So I went with the servants. My father was on his horse looking back at the Palace, and when he saw me coming his eyes lit up and he seemed very pleased. He did not dismount but I was lifted up and he held me against him so tightly that it was painful. I felt he was trying to say something and did not know how to, but he hated to let me go. I thought he was going to take me to Innsbruck with him, but this could not be, for my mother would have arranged that if it were so.

His hold loosened and he looked at me tenderly. I threw my arms about his neck and cried: “Dear, dear Papa.” There were tears in his eyes and he gripped me with his right arm while he touched my hair with his left. He had always liked to touch my hair, which was thick and light in colour—auburn, some called it, though my brothers Ferdinand and Max called me “Carrots.” His servants were watching, and abruptly he signed to one of them to take me from him.

He turned to the friends who were beside him and said in a voice shaken with emotion: “Gentlemen, God knows how much I desired to kiss that child.”

That was all. Father smiled goodbye and I went back to the schoolroom, puzzled for a few minutes, and then characteristically forgot the incident.

That was the last I saw of him. In Innsbruck, he felt rather ill and his friends begged him to be bled, but he had arranged to go to the opera with Leopold that afternoon and he knew that if he were bled he would have to rest and cancel the opera, which would worry Leopold, who, like all his children, loved him dearly. It was better, he said, to go to the opera and be quietly bled afterwards without disturbing his son.

So he went to the opera and was taken ill there. He had a stroke and died in Leopold’s arms.

It was naturally said afterwards that he, being near death, had had a terrible premonition of my future and that was why he had sent for me in that unusual manner.

We were all desolate because we had lost our father. I was sad for several weeks and then it began to seem as though I had never known him. But my mother was heartbroken. She embraced my father’s dead body when it was brought home and she was only removed from it by force.

Then she shut herself into her apartments and gave herself up to grief which was so violent that the doctors were forced to open one of her veins in order to give her relief from her terrible emotion. She cut off her hair—of which she had been so proud—and she wore a widow’s sombre costume, which made her look more severe than ever. In the years which followed I never saw her differently dressed.

After my father’s death, my mother seemed to become more aware of me.

Before, I had been just one of the children, now I would often find her attention focused on me during those occasions when we all had to wait on her. This was alarming, but I soon discovered that if I smiled I could soften her, just as I could dear old Aja, though not so easily and not always; and of course I tried to cover up my shortcomings by using this gift of mine for making people indulgent towards me.

It was soon after Father’s death that I began to hear talk of “The French Marriage.” Couriers were constantly going j back and forth with letters between Kaunitz and my mother and my mother’s ambassador in France. ;

Kaunitz was the most important man in Austria. A dandy, The was nevertheless one of the shrewdest politicians in Europe and my mother thought very highly of him and trusted him more than she trusted anyone else. Before he became her j chief adviser he had been her ambassador at Versailles, where he had become a great friend of Madame de Pormpadour which had meant that he was well received by the King of France, and it was while he was in Paris that he had conceived the idea of an alliance between Austria and France which would be through a marriage between a the houses of Hapsburg and Bourbon. Living in France had given him the manners of a Frenchman, and as he also dressed like one, in Austria he was considered rather eccentric. But he was very much a German in some ways-calm, disciplined and precise. Ferdinand told us that he osed egg yolks for his complexion, smearing them over his face to keep his skin fresh; and to preserve his teeth he used to clean them with a sponge and a scraper after every meal—at the table. He was so determined that his wig should be powdered all over that he ordered his valets to form two rows between which he walked while they used their bellows. He was enveloped in a cloud of powder, but this ensured that his wig was evenly powdered.

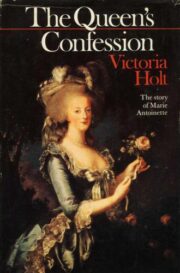

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.