‘Of course, since you let her have her way! Oh you were always so mild, Marguerite. You don’t know what it is to have deep feelings.’

‘I have had great adventures in my life, Eleanor,’ Marguerite defended herself, ‘and I think I have lived more dangerously than you ever did.’

‘I was near death in London. I shall never forget the evil faces of the mob as they looked down on me from the bridge. I knew they intended to sink my barge. It was awful. Sometimes I dream of them now … I hear their voices shouting “Drown the Witch.” You could not understand, Marguerite.’

Marguerite laughed.

‘I will tell you something, sister. You have forgotten that when Louis went on his crusade to the Holy Land, I accompanied him. The fear you experienced during one night in London, was with me constantly for months. I was a woman in that strange land. We were in perpetual danger from the Saracens. Do you know what they did to women if they captured them? They might torture them; they might merely cut off their heads; but what was most likely was that they took them off to serve in some harem. You dream of London Bridge. My dear sister, I dream of the Christian camp where I, heavy with child, waited night after night for some fearful fate to overtake me. Often the King left me. I was in the camp with only one knight to protect me. He was so aged that he could not join the others. I made him swear that if ever the Saracens came to my tent he would cut off my head with his sword rather than let me be taken.’

Eleanor was subdued. It was borne home to her that her own joys and sorrows had always seemed so much greater than those of others that she had rarely thought theirs worth considering.

Now to think of Marguerite, pregnant, lying in a desert camp, was sobering.

‘But that is all in the past,’ she said. ‘My trouble is here right before me.’

‘All troubles pass,’ Marguerite assured her. ‘Yours will no less than mine did.’

‘Does that mean I should not do everything I can to disperse them?’

‘Nay, you would always work for your family. But be patient, dear sister. All will be well.’

But it was not in Eleanor’s nature to sit down and wait for miracles. She redoubled her efforts.

One day Edward de Carol, the Dean of Wells, arrived in Paris. He had letters from the King, he said, and joyfully Eleanor seized on them.

When she read what the King had written she was filled with a dull anger. He begged her to desist in her efforts to interfere with the course of events. What she was doing was known in England. It could do no good.

The Dean did not have to tell her that the letter had been dictated by her enemy Simon de Montfort, because she knew as soon as she read it.

She remembered Marguerite’s admonition to be patient. She wrote back to the King assuring him that she would respect his wishes.

When the Dean had left she went on with her work. She was certain that in time she would raise an army.

Messengers continued to come to the Court of France and they brought news of the royal captives. It was thus that she learned that they had been taken to Dover. The nearest port to France. Wild ideas filled her mind. Would it be so very difficult to get a party to land, to storm the castle, to rescue the captives and bring them to France? There they could place themselves at the head of the army she was sure she would raise. They would be free to win back the crown.

While she was turning this over in her mind and making plans to bring it about, more messengers came.

The barons felt that Dover might be a dangerous spot in view of its proximity to the Continent. They were therefore being moved to Wallingford.

She could have wept with rage, but very soon she was making fresh plans.

Her indefatigable efforts had won the admiration of a number of people and her devotion to her family was touching. Even those who found her overbearing were ready to work for her and thus there were plenty to bring her news of what was happening in England. The royal prisoners, she learned, were not so well guarded at Wallingford as they had been at Dover. One of Edward’s favourite knights had sent word to her that he would do anything to help the royal cause and she immediately decided to keep him to his word.

Sir Warren de Basingbourne was a young and daring fellow who had often jousted with Edward and whom she knew was devoted to her son.

‘Gather together as many men as you can,’ she wrote to him. ‘Go to Wallingford, lay siege to the castle – which I know to be ill defended. Rescue the lord Edward. He can then come to me here and place himself at the head of the army I am preparing.’

Eleanor excitedly settled down to await the arrival of her son.

Edward had never ceased to reproach himself. This disaster was due to his folly. It was no use his father’s trying to comfort him. It was clear that if he had not pursued the Londoners the victory would have gone to the King.

What folly! What harm inexperience could do!

Edward was a young man who quickly learned his lessons.

He thought often of his young wife with whom he was in love. It had been a marriage after his own heart. She had been so young at the time of the ceremony and he had seemed so much older to her that she had begun by looking up to him. They had been separated, it was true, while she completed her education and grew old enough to be his wife in truth. And then he had not been disappointed in her.

He believed she was now pregnant.

Poor little Eleanora – or Eleanor as they insisted on calling her, for their future Queen must have an English name – she would be fretting now, as he knew his mother was.

He was glad his cousin Henry was with him, although it would have been more satisfactory if he could have been free to work for the King. They played chess together; they were even allowed to ride out although only in the castle surrounds and in the company of guards. Simon de Montfort treated them with respect. He was always anxious for them to know that he had no intention of harming them, and that he merely wanted to see just rule returned to the country.

While they sat at the chess table one of their servants came running in. He was clearly very excited.

‘My lord,’ he said, ‘there is a troop of men marching on the castle.’

‘By God,’ cried Edward. ‘The country is rising against de Montfort.’

They rushed to the windows. In the distance they could see the horsemen making straight for the castle.

Someone said: ‘They are Sir Warren de Basingbourne’s men, I’ll swear.’

‘Then they come to save us,’ said Edward. ‘Warren would never place himself against me. He is my great friend.’

There was activity throughout the castle. At the turrets and machicolations soldiers were stationed. The alert ran through the castle. ‘We are besieged! Stand by for defence.’

It was frustrating for the prisoners to be unable to take part in the fighting as they were forced to listen to the shouts and the cries and the groaning of the battle engines as they went into action.

Edward heard his own name called.

‘Edward. Edward. Bring us Edward.’

His eyes were shining. ‘Our friends have risen at last,’ he said. ‘I knew it was only a matter of time. Our captivity is over.’

‘First they have to break the siege,’ Henry reminded him.

‘By God they will. We are poorly defended here.’

Half a dozen guards had come into the room.

They approached Edward.

‘What would you have of me?’ he demanded.

‘We but obey orders, my lord.’

‘And they are?’

‘Your friends out there are demanding that we bring you out to them.’

‘And you, knowing yourself beaten, are meeting their wishes?’

‘We are not beaten, my lord. But we are giving you to them. We shall bind you hand and foot, as we shall tell them, and we shall shoot you to them from the mangonel.’

Edward cried out in horror at the thought of being shot through this terrifying engine which was used for throwing down stones on the enemy. It would be certain death.

‘You do not mean this.’

‘It will be done, my lord, if your friends do not go away.’

‘Let me speak to them.’

The men looked at each other and one of them nodded and retired.

When he returned he said: ‘Orders are that your hands should be bound behind your back, my lord. Then we will take you to the parapet. From there you will speak to your friends. If you tell them to go away, your life will be saved.’

‘I will do it,’ he said, for indeed there was no alternative but terrible death. So they tied his hands and he stood on the parapet and told them that unless they wanted his death they must disperse and go away, for his captors meant that if he came to them it would be by way of the mangonel.

Sir Warren hastily retired; and when news of what had happened was sent to Eleanor she wept with anger.

Simon de Montfort came in all haste to Wallingford. The news of Basingbourne’s attempt had shocked him. It could so easily have succeeded. It had been a brilliant idea to threaten to shoot Edward out to them. However, an ill-defended castle was no place for such prisoners.

In the hall of the castle all the prisoners were brought to him.

‘My lords,’ he said, ‘I am grieved that you have been treated with less than respect. I assure you that it was no intention of mine.’

‘You do not make that intention very clear,’ retorted Edward.

‘I am sorry if you have not perceived it,’ replied Simon calmly. ‘It is true that your movements are restricted but I trust you lack no comfort here in the castle.’

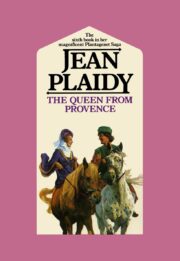

"The Queen from Provence" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen from Provence". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen from Provence" друзьям в соцсетях.