‘My lord, I could paint a picture no matter what the subject.’

‘Then here is a subject for you. It will show future generations what I had to endure from those who should have served me best. Rest assured, you will be paid well.’

The monk bowed his head and the King passed on. As he continued to paint the picture of the Abbey William was thinking that the King was overwrought and small wonder if rumours he heard were true. There was trouble brewing, and when a King’s subjects were restive and ready to rise against him it needed only one little spark to set the conflagration going.

The King would forget he did not doubt and he was surprised when the following day he was summoned to appear before him. That very day the picture was begun.

When it was finished, the King declared himself well pleased. There was no mistaking the meaning there.

Henry said: ‘It shall be placed in my wardrobe here in Westminster. I come here when I wash my head and I shall never fail to look at it and marvel at the ingratitude of those men whose duty it is to obey me. I have commanded my treasurer Philip Lovel to pay you for your work. You have done well.’

So the picture was hung and for several weeks the King would look at it every morning when he came into his wardrobe. After a while he forgot, for Simon de Montfort, realising that the country was as yet unripe for rebellion, left for France.

There was trouble in Gascony and the King’s presence was needed there.

He told the Queen that he would have to go and he could not bear to be parted from her.

‘Then I will come with you,’ she said.

Henry frowned. ‘I could not contemplate going without you but I am afraid to leave the country.’

‘That wretched de Montfort is no longer here. The people seem to be coming to their senses.’

Henry shook his head. ‘It is not quite the case. People do seem to hate us less, but we have enemies all about us. We cannot afford trouble in Gascony now. I want at the same time to see Louis … to sound him … perhaps to get his help.’

‘You think he would give it?’

‘No king cares to see another deposed.’

‘Deposed! You don’t think they would dare?’

‘They tried to do it to my father. That was the worst thing that ever happened to the monarchy. It lives for ever in their minds. I think Louis would not wish to see me toppled from my throne. It sets a precedent. He might help.’

‘He should help,’ said Eleanor. ‘After all he is Marguerite’s husband.’

‘Alas, my love, all have not such strong family feeling as you are blessed with.’

‘I must come with you, Henry. I insist. You have not been well of late.’

‘The thought of going without you makes me desolate indeed.’

‘We have a son. Let Edward return to England. He is of an age now to take the reins in your absence. Oh, my dear Henry, you hesitate. No child of mine would ever stand against his father.’

Henry took her hand and kissed it. ‘I see you are right as you so often are. I should let myself be guided by you. Edward shall return. Our son will take charge of matters here in our absence; and you and I will not be parted.’

The Queen was to be grateful that she had accompanied the King for it seemed that luck was against him. When in France he was smitten with a fever which rendered him very feeble and even endangered his life, and but for the untiring nursing of the Queen he might have died. Without her, he admitted, he would have felt listless and in no mood to fight for his life. But she was here to make sure that he had doctors and attention and everything possible to sustain him. Most of all she assured him that he must live for the sake of her and the family.

She reminded him how Edward had sobbed when he had sailed for France years ago when Edward was but a boy; she recalled Margaret’s recent visit. Did it not show how loved he was?

Was it so important that his subjects were ungrateful and easily led astray when he would always have his beloved family beside him? He must think of them, for if he did not fight for his life and keep his hold on it he was condemning them to such misery as he could well understand, for what misery would he know if she, his wife and Queen, were taken from him.

He began to recover under the Queen’s ministrations but he had not achieved the purpose of his visit. He had been several months in France; the trouble in Gascony had resolved itself but Louis was not inclined to offer material help. All he could give was advice which was something Henry thought he could do well without. Henry returned to England.

Simon de Montfort was back and his absence had endeared the rebels to him. They had feared that he had wearied of the struggle and had left them to fight the battle with the King, and on his return he was welcomed with such enthusiasm that it seemed the moment was ripe to start bargaining with the King.

They agreed to meet the King and Simon arrived with a party of barons led by himself and Roger Bigod of Norfolk.

The Provisions of Oxford must be adhered to, said the barons. These have been laid down by the Parliament and even the King must accept the wishes of his people.

Roger Bigod said: ‘My lord, since your return from France you have brought even more foreigners into the country. This is against the wishes of your people.’

‘My lord Norfolk,’ answered the King, ‘you are bold indeed. You forget whose vassal you are. You should go back to Norfolk and concern yourself with threshing your corn. Remember, I could issue a royal warrant for threshing out all your corn.’

‘That is so,’ retorted Bigod. ‘And could I not reply by sending you the heads of your threshers?’

This was defiance, and Henry was never quite sure how to act in such situations. He looked angrily at the barons who were watching him closely. One false move and that could be the spark to start the fire.

A curse on Bigod and a greater one on de Montfort!

Henry knew they were poised for action.

He shrugged his shoulders and dismissed the meeting. But he had betrayed his weakness.

‘The time is near for us to strike,’ said Roger Bigod.

There was tension throughout the land. Neither the King nor the Queen dared ride out unless they were protected by armed bands. Henry was fast fortifying his castles and those which were of the most importance, the Tower of London and Windsor Castle, were equipped as for a siege.

London was ready to rise. The citizens had had enough taxation. There was no possibility of getting rich, for as soon as their trade increased the King or the Queen would invent a new tax as a means of taking their profits from them.

Those who suffered most were the Jews, but this did not endear them to the other citizens who were irritated by the Jewish ability to rise above persecution, to pay the exorbitant taxes and then in a short time become rich again. It was not natural, said the London merchants.

Punitive measures had been introduced against the Jews. There should be no schools for them; in their synagogues they should pray in low voices so that they did not offend Christians. No Christian should work for a Jew. No Jew should associate with a Christian woman or Christian man with a Jewess. Jews should wear a badge on their breasts to denote their race. They must never enter a Christian church. They must have a licence to dwell in any place. If any of these rules were disobeyed there should be an immediate confiscation of their goods.

All these rules the Jews could overcome; what made life impossible for them was the excessive taxation. Yet even so they would make the most of the periods when they were left alone and always seemed to prosper quickly.

This gave rise to great envy and there were constant skirmishes when Christians would attack the Jews always in such a way as to enable them to rob them of their possessions.

The Queen was at the Tower and the King at Windsor with Edward. She was aware of unrest in the streets and did not venture out because she was told that the mood of the people was uncertain and as always it would be against her.

She told her women that she would be easier in her mind if she were with the King and she thought it might be an excellent idea the next day to take a barge to Windsor. This suggestion met with the immediate approval of all whose duty it was to protect her.

Unfortunately that very night there were plans afoot to attack the Jews. The mob had arranged that at the sound of St Paul’s bell at midnight they would assemble and march against them surprising them in their beds so that they would not have time to hide their possessions.

The Queen in her chamber heard the bell strike and almost immediately there was shouting and screaming in the streets. The attack on the Jews had started.

Into the houses occupied by Jews streamed the mob, shouting and screaming vengeance. Throats were cut, bodies mutilated, but the main purpose was to appease envy and greed by robbery.

The Queen dressed hurriedly and sent for guards.

‘What goes on?’ she demanded.

‘My lady, the people are running wild in the streets. They are robbing and murdering the Jews. There will not be many left in the city of London this night.’

‘We should not be here. Who knows where such violence will end.’

The guards agreed that the people, knowing she was at the Tower of London, might, when their evil work was done with the Jews, turn to her. They were in a violent mood and the lust for blood was on them. It could be said that the people’s hatred of the Queen was as great as that they bore towards the Jews.

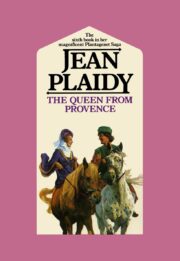

"The Queen from Provence" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen from Provence". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen from Provence" друзьям в соцсетях.