Secretly Henry did not find babies beautiful but he said nothing as he did not want to contradict the Queen.

‘Take his hand, Henry,’ said the Queen. ‘Gently. Remember he is but a baby. There. Now say: Edward I will be your friend.’

‘Can I be friends with such a little baby?’ asked Henry.

‘He won’t be a baby always. He’ll grow up very quickly, then you won’t notice that he is younger than you. Come. Say it. Say you will be his friend.’

‘I will be your friend … if I like you,’ said Henry.

Everyone laughed and the King said fondly: ‘Our nephew is too young yet to swear fealty.’

‘Kiss his hand,’ insisted the Queen.

Henry took the baby’s hand and kissed it.

And the Queen seemed satisfied.

He was then given to the nurses who were told that he would stay in the royal household until such time as his father wished him to depart. As there were other boys of noble families living at Court – after the custom – no one was very surprised to see the son of the Earl of Cornwall among them.

Richard went away to make his last preparations for the crusade with the conviction that Isabella’s death had really been a happy release not only for herself but for her son and husband.

Chapter VIII

A SOJOURN IN PROVENCE

The King accompanied Richard to Dover where on a hot June day he set sail for the Continent. Among those who left with him was Peter de Mauley who had been his old tutor and governor in the days of his childhood at Corfe Castle. Many distinguished knights, eager to win honours and a remission of their sins in the Holy War, formed his company. So it was an impressive party that left the castle to take ship for France.

The King watched the departure with mixed feelings. He could not in honesty say that he wished he were going with them. The thought of leaving Eleanor and their son filled him with horror. Of course Eleanor might have accompanied him as his grandmother Eleanor of Acquitaine had once gone with her first husband to the Holy Land and created such a scandal there that it had never been forgotten. But little Edward could certainly not have gone and one of the great joys of Henry’s life was to slip away into the nursery and gaze at that wonderful child with the perfect limbs and the healthful looks – his son, who would one day be King of England.

Moreover he was glad to have Richard out of the country. He knew that Richard disapproved of much that he did and that chiefly he objected to the favour he showed to foreigners – foreigners being Eleanor’s relations and retainers.

As if they were foreigners! Dear Uncle William now dead. How Eleanor had loved him! He was glad he had been able to show his appreciation to him before he died. And he was going to do all he could for Uncle Thomas and it was now being suggested that her Uncle Boniface would come over to England too.

She was delighted. The uncles had been a part of her childhood. Little gave her as much pleasure as to receive them in England and show them how happy she was in her marriage. And since it delighted her, he also was delighted.

But some of the killjoys in his kingdom wanted to spoil that – and he feared Richard was one of them. He had said before he left that the Bishop of Reading was deeply disturbed by the intrusion of the Queen’s relations and had urged him not to leave England at this time.

‘Why not? Why not?’ Henry demanded.

‘Because,’ Richard had said, ‘he fears that the barons are growing more and more displeased by these foreigners coming here.’

‘Why should they not come here?’ Henry had asked. ‘They are my wife’s relations.’

‘If they merely came that would give little offence. The point is that when they are here they proceed to fill their pockets and take that which by rights belongs to Englishmen. If they leave – as in the case of the Bishop Elect of Valence – they certainly do not go empty-handed.’

‘I am surprised,’ Henry had said piously, ‘that you can speak ill of the dead.’

‘I trust I speak the truth of anyone … dead or alive,’ had been Richard’s retort.

He had gone on the crusade though and Henry was not going to let himself be disturbed by the vague murmurings of the barons. It was a great pity they had ever been allowed to produce Magna Carta which had given them too high an opinion of their own power.

He returned to London where Eleanor was awaiting him and together they went to the nursery to gloat over Edward.

‘I am not sorry he has gone,’ said Henry. ‘He is full of apprehension about the future. He talks continually of the barons’ displeasure. One would think they ruled this country.’

‘Perhaps now he will find a suitable wife and settle down. That is what he needs.’

Henry slipped his arm fondly through hers.

‘I believe you have a fondness for Richard,’ he said.

‘Naturally, but for him you and I would never have been brought together.’

‘Well, for that I will forgive him a great deal,’ said the King.

Arrived in France Richard began his journey across the country and when he reached Paris he was greeted by the King of France, his wife and mother who gave him a very royal welcome.

He was impressed by the young King – as indeed all must be, for his was a character of great distinction and there was a nobility in his face, bearing and manner of which none could be unaware.

His mother adored him; she had worked for him as tirelessly as she had for his father and although Louis IX had shown himself very capable of governing his kingdom – far more so than his father had ever done – she still seemed to be under the impression that she was needed.

Richard was interested to meet Marguerite, the sister of Henry’s Eleanor. A beautiful woman but lacking Eleanor’s forceful nature. Richard wondered what would have happened if they had changed roles and Eleanor gone to France and Marguerite to England. Queen Blanche would not have had the easy victories over Eleanor that she clearly had over Marguerite.

Marguerite was eager to talk to him. She wanted to know all the news of England and how Eleanor lived there. She plied him with questions and talked about her own life and how fortunate she was to have such a husband as Louis.

‘I doubt not that you could have wished for a mother-in-law who was not ever present.’

Marguerite was silent, not wishing to speak ill of Queen Blanche.

‘The King’s mother is ever alive to his interests,’ she said.

‘I doubt it not,’ replied Richard. ‘I see how often he is in her company.’

‘He came to the throne when he was only a boy. She had to be there then to guide him.’

‘He would seem to be a King who knows which way he is going and needs no guidance now.’

‘He will do as he thinks best, but he loves her dearly and he is always sad when it is necessary to go against her will.’

‘And you?’ asked Richard. ‘Do you not find her sometimes taking him from you?’

Marguerite was silent and Richard thought of what he would say to Eleanor when he returned to England.

There was another matter in which Eleanor had been more blessed than her sister: Eleanor had a son; Marguerite only a daughter – and even then the child had to be called Blanche.

In a way, mused Richard, it seemed that Eleanor had made the more fortunate marriage. But this was not entirely so. Richard was looking into the future. The strong character of Louis IX, the determination to rule well, the clever logical calm mind … these were the making of a great King. Louis would have the reins of government firmly in his hands.

Richard wondered then if there might come a day when the barons decided they would rise once more in England as they had under King John, when they would tire of a King on whom they could not rely. How would Henry stand the strain? And Eleanor? Did she realise that the people were murmuring against her, that they could not forgive her for bringing her family and friends to England and keeping their pockets well filled?

There could be no doubt who was the greater King; and if Marguerite had a forceful mother-in-law and so far only a girl child – who could not inherit the throne because of the Salic law which existed in France – perhaps her position was after all more secure than that of her sister Eleanor.

‘It has been wonderful to have news of my sister,’ said Marguerite. ‘I often think of the days when we were all together in the nursery – the four of us. How happy we were! Then I went away and the three of them were left. There will only be Sanchia and Beatrice now.’

‘I remember too when I went there and saw the three beautiful princesses. That was after I had read Eleanor’s poem.’

‘Yes, that was so romantic. But for her poem … she might not now be Queen of England. She must be ever grateful to you for I know she is very happy.’

‘Her uncles have been to England to see her,’ said Richard, his mouth tightening a little.

‘How contented she must have been!’

He did not say that the people of England had been a good deal less content.

‘Eleanor was always devoted to the family,’ went on Marguerite, ‘as we all were.’

‘Do they not visit you in France? They are much nearer to you.’

‘They come. But they do not stay long.’

Wise Louis! thought Richard. He has more sense than to spend his country’s revenues on his Queen’s impecunious uncles.

‘They stay in England,’ said Richard.

‘I have heard that the King is very generous to them.’

‘More generous than he can afford to be, I fear.’

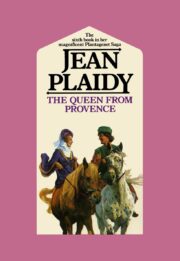

"The Queen from Provence" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen from Provence". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen from Provence" друзьям в соцсетях.