In her own room Lehzen tried to tempt her with food but she could not touch it, but as the evening wore on she grew a little calmer.

‘Lord Melbourne expects me to be calm,’ she told Lehzen. ‘He says I must behave as if this is merely a change of Government which it is obvious I would rather not have taken place, but I must show that I am ready to work with these people.’

‘And Lord Melbourne is right. You used to say he always was.’

She sat brooding until midnight; then she went to bed and to Lehzen’s relief slept soundly.

As soon as she awoke next morning she wrote to Lord Melbourne.‘The Queen thinks Lord Melbourne may possibly wish to know how she is this morning; the Queen is somewhat calmer; she was in a wretched state till nine last night when she tried to occupy herself and to think less gloomily of this dreadful change and she succeeded in calming herself till she went to bed at twelve and she slept well; but on waking this morning all – all that had happened in one short eventful day came forcibly to mind and brought back her grief; the Queen, however, feels better now; but she couldn’t touch a morsel of food last night nor can she this morning. The Queen trusts Lord Melbourne slept well and is well this morning; and that he will come precisely at eleven o’clock …’

She was sitting brooding in her room waiting for eleven to come when the Duke of Wellington was announced.

‘It is not a bad dream,’ she mourned. ‘It really has begun.’

The great Duke was seventy and seemed quite ancient to the young Queen. The idea of his taking the place of her beloved Lord Melbourne was grotesque – yet just a little better than horrid Peel’s doing so.

‘Your Majesty!’ said the Duke bowing.

‘Pray be seated,’ replied the Queen. ‘Now I suppose you know why I have sent for you?’

‘I have no idea,’ replied the Duke.

A fine future leader of Government, she thought, who doesn’t know what is going on!

‘Lord Melbourne’s Ministry, in which I had the greatest confidence, has resigned.’

‘I am grieved to hear it.’

‘As your party has been instrumental in removing them,’ said the Queen with a flash of temper, ‘I am obliged to look to you to form a new Government.’

‘Your Majesty, I have no power whatsoever in the House of Commons. I can only advise you to send for the leader of the Opposition there – Sir Robert Peel.’

The Queen’s lips tightened and the Duke went on: ‘Your Majesty will find him a man of honour.’

The Queen ignored this and said that she hoped the Duke would have a place in the Cabinet.

‘Your Majesty, I am seventy years of age. My prime is long past. I am so deaf that it is difficult for me to take part in any discussion.’

‘I have more confidence in you than in any other member of your Party. You understand the …’ her voice faltered … ‘the great friendship I feel for Lord Melbourne.’

‘I do understand that,’ replied the Duke, ‘and I have the utmost respect for Lord Melbourne. I believe that he can continue to be of use to Your Majesty.’

‘And now I suppose I have no alternative but to send for this Sir Robert Peel.’

The Duke assured her this was so.

When she saw Lord Melbourne at eleven she was less stubborn, he was glad to see. Her good sense was prevailing. She had been made extremely unhappy by what had happened but she saw that she would have to accept it.

‘I am proud of you,’ said Lord Melbourne with tears in his eyes.

Sir Robert was feeling very uneasy as he drove to the Palace in answer to the Queen’s summons. He was fifty-one years of age, a power in the House of Commons and a natural reformer; but he was well aware of the great success Lord Melbourne had had with the Queen – it had been the talk of the Court and the country and was even creeping into the press – and he knew that he lacked those suave social graces which Melbourne possessed. Moreover he was conscious that the Queen did not like him.

She could convey her disapproval by a glance and a cold nod and these had come his way on the rare occasions when he had been in royal company.

He had talked the matter over with his wife Julia that morning. With her he shared his innermost thoughts; she understood him as no one else did, and therefore was well acquainted with the idealist who existed beneath the cold façade.

‘I am inevitably being called to be asked to form a Government,’ he had told her.

‘Well, you will do exactly that,’ Julia had replied with a smile.

‘We shall be in a minority and the Queen will be against us.’

‘The Queen, Robert, is just a child.’

‘A child of some importance,’ he had replied with a smile. ‘And Melbourne is her god.’

‘Which shows what a child she is. But queen or child when one Government falls she must accept another.’

‘I fear it will be a rather trying interview.’

Julia had laughed. ‘Oh, come now, you are not going to be frightened of a chit of a girl.’

‘If we were strong. If we were an elected Government with a big majority it would have been another matter.’

‘Is this the great politician speaking – the man who revised the laws of offences against persons, and laws against forgers, who created the police force? Oh, come, Sir Robert Peel.’

‘Everyone doesn’t see me as you do, Julia.’

‘Because you won’t allow them to. You are going to see the Queen and you know that she will have to accept you. And if she is going to be annoyed with you because you have replaced Melbourne, well then she does not understand the Constitution which she is supposed to rule; and if she is wise she will very shortly learn that you are a greater statesman than Melbourne could ever be.’

‘Melbourne knows how to charm her.’

‘His job was to govern England not to charm the Queen.’

‘He managed to do both it seems.’

‘He certainly did not do both successfully for here he is forced to resign. What did Melbourne ever do but let things run along just as they were? You know very well he hates all change. That’s no way to govern. And if the Queen likes him, the people don’t. He’s made himself very unpopular over this Flora Hastings affair.’

Sir Robert was thinking of this as he drove along. It was true that Melbourne was not the most successful of Prime Ministers and Peel was convinced that he himself would make a better one. Julia was right. What did it matter if Melbourne could make more of a show in a drawing-room? It was statesmanship the country needed – and the Queen would learn that.

He was too sensitive, and for that reason he presented this cold façade to the world. He was painfully aware of his social inadequacies, but it was true as Julia had said that he was a good politician. He had the welfare of the people at heart which was more than could be said for some, including the sybaritic Lord Melbourne. He had put on court dress which he hoped would please the Queen, and in any case the etiquette of the occasion demanded it, and as his carriage drew up he noticed that little groups of people stood about near the Palace watching for callers.

He heard his own name mentioned amid a buzz of excitement. ‘That’s Sir Robert Peel.’ They knew why he had come.

They were not, of course, concerned about the Jamaican Bill. They were agog with excitement because the Queen’s name was being linked with that of Lord Melbourne and if Lord Melbourne was no longer Prime Minister the Queen could not – without causing a great deal of comment – see him so frequently as she had hitherto.

He was shown into the yellow closet where the Queen was waiting for him. She had refused to see anyone in the blue closet. That was sacrosanct because it was there that so many of her meetings with Lord Melbourne had taken place.

‘Sir Robert Peel.’

He bowed – so awkwardly, she noticed.

‘At Your Majesty’s service.’

He was tall, and his rather plentiful hair was untidy. Such a fidgety man, thought Victoria angrily.

‘You know, of course, Sir Robert Peel, why I have sent for you?’

He bowed his head in acquiescence.

‘I am grieved … beyond words,’ said Victoria coldly. ‘I am filled with the greatest regret to be obliged to part with Lord Melbourne’s ministry. Lord Melbourne served me well from the time of my accession.’

She looked critically at Sir Robert as though implying that he could not fail to displease her. She was the Queen, as she knew so well how to be and although when he had left his home he had agreed with his wife that she was only a child, he was overawed by her regality in the yellow closet.

He murmured that it would be the earnest endeavour of Her Majesty’s new Government to serve her with all the power at its command.

The tilt of her slightly open lips suggested that she had no great confidence in his Party, and that she had in fact no great confidence in Sir Robert Peel, and she was wishing with all her heart that he had had the good sense not to oppose her dear Lord Melbourne.

‘We believed in our late Government,’ she said. ‘We approved all that they did.’

It was very difficult to talk to such an imperious Sovereign who had made up her mind so definitely, but Sir Robert must get down to the purpose of his visit.

‘I hope, Sir Robert,’ she said sternly, ‘that you are not going to insist on the dissolution of Parliament.’

‘Your Majesty will know that in the circumstances this seems a reasonable course of action.’

‘We should not wish that and I ask you to give me your assurance that you will not do so.’

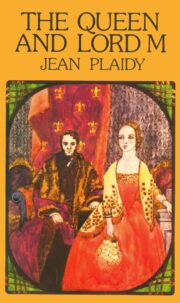

"The Queen and Lord M" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen and Lord M". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen and Lord M" друзьям в соцсетях.