As she said afterwards to Charles, to hear such compliments from a kind impartial friend was so gratifying.

He gently advised her that she should go to bed. ‘For,’ he added, with that charming solicitude, ‘you are far more tired than you think you are.’

‘Well, I did sleep rather badly last night.’

‘The Coronation was on your mind,’ he replied. ‘Nothing keeps people awake more than the awareness of a great event and being somewhat agitated about it.’

So Lord Melbourne took his leave and there was nothing after that to stay up for.

Several of the party had gone on to one of the balconies to see the illuminations. Victoria did not join them but went alone to the balcony of her mother’s apartments, where she could watch the firework display in Green Park.

As she stood there, she went over the events of the day, feeling very solemn and dedicated and so thankful that she had her precious Lehzen beside her and her dear good, kind, impartial friend, Lord Melbourne, to guide her.

She slept soundly that night and as soon as she was awake she thought of Lord Melbourne and wrote to him:‘The Queen is very anxious to hear if Lord Melbourne got home safe, and if he is not tired and quite well this morning.’

Chapter VII

PALACE GOSSIP

Nothing was quite the same after the Coronation. When she had ridden through the streets the people had adored their charming young Queen and she had reached the top of her pedestal, but it was going to be very difficult to stay there.

There had always been scandals about the lives of Royalty; the people had come to expect them; and though it might be difficult to imagine that anything shocking could be happening in the life of a young girl who was so clearly innocent, that did not stop malicious people from speculating on the situation at the Palace.

Victoria in her innocence was unaware of this. She was enjoying her role, applying herself to it assiduously. She was sure that she possessed a natural aptitude for it and as long as she had her dear Prime Minister to guide her in public life and her precious Lehzen in private, what more could she ask?

When the Court was at Windsor, naturally Lord Melbourne and any other visiting Ministers had their own apartments there, but this was not the case in Buckingham Palace where it was easy for a minister to pay a brief visit whenever he was required to do so. As far as Lord Melbourne was concerned though, he was so often at the Palace that it seemed advisable for a set of apartments to be put at his disposal there; and he did in fact live more often at Buckingham Palace than Melbourne House. This was an ideal arrangement, said the Queen, for it meant that she could call on him so easily at any time. Lord Melbourne agreed with her.

Trouble was brewing in the Palace and at the heart of it was Sir John Conroy, whom Victoria had suspected of treachery before her accession. Her suspicions were now confirmed.

‘It is not only the Duchess’s financial affairs which are controlled by him; she herself seems to be,’ commented Lord Melbourne.

He spoke very frankly to Victoria now because as he said they understood each other and it was only if he spoke his mind that he could let her know what was in it. The Duchess showed quite clearly that she disliked Lord Melbourne, so Lord Melbourne retaliated; and as he explained to the Queen, there was no point in his saying what he did not mean out of deference to convention.

‘I should like to see Sir John out of the Palace,’ said the Queen.

‘We could not agree to his demands. You remember they were exorbitant. To do so would be submitting to blackmail.’

‘Odious creature! I always knew I was right to hate him. Sometimes I think that it would be a good idea to get rid of him at any price. Suppose we made it worth my mother’s while to go abroad? Back to Leiningen perhaps. Then That Man could go with her.’

Lord Melbourne considered this. ‘Would she go? And if she did, you could not live alone without some chaperone. It might make trouble too. The people would not like to see an open rift between you and your mother. You manage everything so well by being affectionate towards her in public. It is best to continue like that.’

‘It seems so insincere. I don’t like it.’

‘Ah, you are open and frank by nature,’ said Lord Melbourne admiringly, ‘but sometimes we all have to do things we don’t much like … particularly queens.’

‘Mamma has been much more humble lately. I think she would like a reconciliation.’

‘Let her begin negotiating for it by sending Conroy away.’

‘She has written to Lehzen – such a friendly letter.’

‘I don’t doubt she is trying to win you back,’ said Lord Melbourne. ‘But it would be best for the Baroness to acknowledge the letter and leave it at that.’

So the battle continued and like good soldiers the ladies-in-waiting and other servants of the Palace fell in behind their leaders. On one side was the Queen, with Lord Melbourne, Lehzen and Baron Stockmar; and on the other side the Duchess with Conroy and Lady Flora Hastings who, because of her rather serious nature and a certain gift for acid comment, led the ladies.

The strained situation with the Duchess drove Victoria into an even closer relationship with Baroness Lehzen. She even declared that she thought of her as Mother and sometimes called her by that name; but of course, reasoned Victoria to herself, she is not my mother, so I shall call her Daisy which I think is a lovely faithful name.

The Baroness was delighted by these outward signs of the Queen’s favour. She could endure the sly allusions to her origins from sharp-tongued Lady Flora; and the sneers about her German habits and her caraway seeds were shrugged aside. All that mattered was that Victoria loved her and had sworn that nothing could ever separate them.

Meanwhile plots fermented in the opposite camp.

Items in the press – not very prominent it was true – were suggesting that there was too much foreign influence at Court. The names Stockmar and Lehzen were mentioned, and of course King Leopold.

‘This has been started by J.C., Mamma and her ladies,’ said Victoria vehemently.

‘It’s nonsense,’ replied Lord Melbourne lightly. ‘Everyone knows that it is Your Majesty’s ministers from whom you take advice.’

‘One of my ministers at any rate,’ smiled Victoria. ‘It is true that dear Stockmar is kind and so devoted.’

‘He is a good intermediary for dealing with Conroy.’

‘Oh how I wish we could rid ourselves of J.C.!’

‘He would go if we acceded to his blackmail. That is what he is waiting for.’

‘I cannot understand why Mamma does not see through him.’

‘If I may be very indiscreet … ?’

‘Dear Lord M, you never are.’

‘Then if I may be exceptionally frank …’

‘You have my permission.’

‘Then I will say that I find the Duchess not very strong-minded and easily led by some. I do not think she is capable of any deep feeling.’

Of course it was wrong to discuss one’s own mother in such a way, but Mamma had become a State matter and this was the Prime Minister.

‘I fear you are right, Lord Melbourne.’

‘Therefore, we must not allow her to dictate our actions.’

‘Most certainly not. Lord Melbourne, what do you think of Lady Flora Hastings?’

‘Frank again?’ smiled Lord Melbourne.

‘Yes, please.’

‘I find her a disagreeable young … or not so young … woman. She must be past thirty. Her family are staunch Tories.’

‘I could well imagine so,’ replied Victoria distastefully. ‘She seems to be very friendly with J.C.’

‘That is understandable. I have always thought there was not an ounce of sense in the entire Hastings family.’

‘I do not find Lady Flora handsome either.’

‘She is positively plain.’

‘I am at a loss to understand why Mamma thinks so highly of her.’

‘A few simple deductions would make the answer clear,’ said Lord Melbourne, and they laughed.

Then they talked of other things – light, frivolous things, and Lord M was so amusing that she could not get to her Journal quickly enough to record some of his witticisms before she forgot them.

The Duchess came to the Queen’s apartments.

‘I thought,’ she said, ‘that my daughter might perhaps wish to see me.’

‘I always wish to see you agreeable, Mamma.’

The Duchess fingered one of the many bows on her dress. ‘My dearest angel,’ she said, ‘isn’t it time to put an end to this sad state of affairs?’

‘What state of affairs is this, Mamma?’

‘This animosity between us.’

‘It is not between us exactly Mamma. It is due to the people who surround us.’

The Duchess leaned forward in her chair.

‘That is exactly true. You see far too much of Lord Melbourne.’

‘My Prime Minister!’

‘Is he not a little more than that?’

‘I don’t think you understand these matters, Mamma.’

‘Oh, I understand very well. You think very highly of that man, now don’t you?’

‘It is of the greatest importance that the Queen should have confidence in her Prime Minister.’

The Duchess’s trouble was that she was unable to control her temper and, as Victoria had inherited a similar one, when these two clashed there were what the Duchess had called in Victoria’s childhood, ‘storms’.

‘Well,’ said the Duchess, ‘that is one way of describing it.’

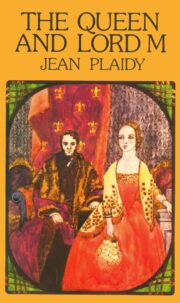

"The Queen and Lord M" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen and Lord M". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen and Lord M" друзьям в соцсетях.