Oh, dear, this was getting worse and worse. If there were just a dark hole in the middle of the hall, Gwen thought, she would be happy to have Lord Trentham drop her into it. The duke was much as she had originally pictured him—tall, slender, and elegant, with handsome, finely chiseled features and dark hair silvering at the temples. His manner was courtly, yet his gray eyes were contrastingly cold and his voice chilly. He spoke of hospitality but made her feel like the worst kind of intruder.

“I am the widow of the late Viscount Muir,” Gwen told the duke. “I am a guest in the home of Mrs. Parkinson in the village.”

“Ah,” the duke said. “She lost her husband recently, I recall, after he had suffered a lingering illness. But off you go on your way upstairs, Hugo. I will hope to have the pleasure of some conversation with you later, Lady Muir, after your ankle has been tended to.”

He made it sound as if it would be anything but a pleasure. Or perhaps her extreme discomfort was causing her to do him an injustice. He was offering hospitality and the services of a physician, after all.

How could one sprained ankle cause such pain? Or perhaps it was broken.

Lord Trentham turned to stride toward a broad staircase that wound upward in an elegant curve. She could hear the Duke of Stanbrook giving orders for both the doctor and Vera to be sent for without further delay. The gentleman with the quizzing glass, the one who spoke with an affected sigh in his voice and a slight stammer, appeared to be offering to perform the errand himself.

The drawing room was empty. That was one mercy, at least. It was a large, square room with wine-colored brocaded walls hung with portraits in heavy gilded frames, and an ornately sculpted marble fireplace directly opposite the door. The coved ceiling was painted with scenes from mythology, the frieze beneath it heavily gilded. The furnishings were both elegant and sumptuous. Long windows looked out upon lawns enclosed by hedges, but they nevertheless afforded a distant view of cliffs and the sea beyond. A fire crackled in the hearth, and the warmth of the room prevented the outdoors from looking too starkly bleak.

Gwen took in room and view at a glance and felt all the humiliation of being an uninvited—and unwelcome—guest in such a home. But for the moment at least there seemed no point in making a fuss and demanding yet again the loan of a carriage to take her back to Vera’s.

Lord Trentham lowered her to a brocaded sofa and reached for a cushion to put under her injured ankle.

“Oh,” she cried, “my boots are going to get the sofa dirty.”

That would be the very last straw.

But he would not let her swing her legs to the floor. Neither would he allow her to bend forward to remove her own boots. He insisted upon doing it for her. Not that he uttered a word of command, but it was difficult to bat aside such large hands and such massive arms or to prevail against such deaf ears.

He had done her a kindness, she admitted grudgingly, but did he have to be so unpleasant about it?

He undid the laces of her left boot and removed it without any trouble at all before placing it on the floor. He went far more slowly with the other boot. Gwen untied the ribbons of her bonnet, pulled it off her head, and dropped it over the side of the sofa so that she could rest her head back against the cushioned arm. She closed her eyes—and then pressed her head back harder and clenched her eyes more tightly as she was engulfed in a fresh wave of agony. He had surprisingly gentle hands, but it was not easy for him to ease off her boot, and once it was off, there was nothing left to support her foot or hold it firm against the swelling. She felt him lift it onto the cushion.

But pain sometimes dulled sensibility, she thought a few moments later as she felt his hands reach under her skirt, first to remove the handkerchief he had wrapped about her knee earlier, and then to roll down her torn stocking and ease it off over her foot.

Warm fingers probed the swelling.

“I do not believe anything is broken,” Lord Trentham said. “But I cannot be certain. You must keep your foot where it is until the doctor comes. The cut to your knee is superficial and will heal in a few days.”

She opened her eyes and was acutely aware of her bare foot and a length of bare leg elevated on the cushion. Lord Trentham was standing upright, his hands clasped at his back, his booted feet slightly apart—a military man at ease. His dark eyes were gazing very directly back into hers, and his jaw was set hard.

He resented her being here, she thought. Well, she had tried very hard not to be. She resented being resented.

“Most women,” he said, “do not bear pain well. You do.”

He was insulting her sex but complimenting her personally. Was she supposed to simper with gratitude?

“You forget, Lord Trentham,” she said, “that it is women who bear children. It is generally agreed that the pain of childbed is the worst pain there is.”

“You have children of your own?” he asked.

“No.” She closed her eyes again and for no apparent reason continued—on a subject she almost never spoke of, even to those nearest and dearest to her. “I lost the only one I conceived. It happened after I was thrown from my horse and broke my leg.”

“What were you doing riding a horse when you were with child?” he asked.

It was a good question, even if it was an impudent one too.

“Jumping hedges,” she said, “including one neither Vernon—my husband—nor I had ever jumped before. His horse cleared it. Mine did not and I was tossed off.”

There was a short silence. Why on earth had she told him all that?

“Did your husband know you were with child?” he asked.

It was an unpardonably intimate question. But she had started this.

“Of course,” she said. “I was almost six months into my confinement.”

And now he would think all sorts of uncomplimentary things about Vernon without understanding at all. It was unfair of her to have said so much when she was certainly not prepared to launch into lengthy explanations. She seemed to have done nothing but show herself in a bad light since she first set eyes upon him and cringed in fear. Yes, she really had. She had cringed.

“This was a child you wanted?” he asked.

Her eyes snapped open and she glared at him, speechless. What sort of question was that?

His eyes were hard. Accusing. Condemning.

But what did she expect? She had made both herself and Vernon seem unpardonably reckless and irresponsible.

It was time to change the subject.

“Is the blond gentleman downstairs a guest at Penderris too?” she asked. “Have I imposed upon a house party?”

“He is Viscount Ponsonby,” he said. “There are six guests here, apart from Stanbrook himself. We gather here for a few weeks each year. Stanbrook opened his home to us for several years during and after the wars while we recuperated from various wounds.”

Gwen gazed at him. There was no outer sign of any wound that might have incapacitated Lord Trentham for that long. But she had been right about him. He was a military man.

“You were or are all officers?” she asked.

“Were,” he said. “Five of us in the recent wars, Stanbrook in previous ones. His son fought and died in the Napoleonic Wars.”

Ah, yes. Shortly before the duchess leapt from the cliff top to her death.

“And the seventh person?” she asked.

“A woman,” he said, “widow of a surveillance officer who was tortured to death after being captured. She was present when he was finally shot.”

“Oh,” Gwen said, grimacing.

Now she felt worse than ever. This was far more terrible than imposing upon a simple house party. And her own sprained ankle seemed embarrassingly trivial in comparison with what the duke and his six guests must have endured.

Lord Trentham had picked up a shawl from the back of a nearby chair and came closer to spread it over Gwen’s injured leg. At the same moment the drawing doors opened again and a woman came inside carrying a tea tray. She was a lady, not a maid. She was tall and very straight in posture. Her dark blond hair was pulled back in a chignon, but the simplicity, even severity, of the style emphasized the perfect bone structure of her oval face with its finely sculpted cheekbones, straight nose, and blue-green eyes fringed with lashes a shade darker than her hair. Her mouth was wide and generous. She was beautiful, despite the fact that her face looked as though it were sculpted of marble. It looked not only as though she never smiled but as if she were incapable of doing so even if she wished. Her eyes were large and very calm, almost unnaturally so.

She came toward the sofa and would have set the tray down on the table beside Gwen if Lord Trentham had not taken it from her hands first.

“I’ll see to that, Imogen,” he said.

“George guessed that you would consider it quite improper to be in a room alone with a strange gentleman, Lady Muir,” the lady said, “even if he did rescue you and carry you back to the house. I have been designated as your chaperon.”

Her voice was cool rather than cold.

“This is Imogen, Lady Barclay,” Lord Trentham said, “who never seems to consider it improper to stay at Penderris with six gentlemen and no chaperon.”

“I would entrust my life to any of the six or all of them combined,” Lady Barclay said, inclining her head courteously to Gwen. “Indeed, I have already done so. You are looking embarrassed. You need not. How did you hurt your ankle?”

She poured three cups of tea as Gwen described what had happened. This, then, she thought, was the lady who had been with her husband when his torturers had killed him. Gwen had an inkling of the torments she must have lived through every minute of every day since. She must forever be asking herself if there was anything she might have done to prevent such a disaster. Just as Gwen forever asked it of herself with regard to Vernon’s death.

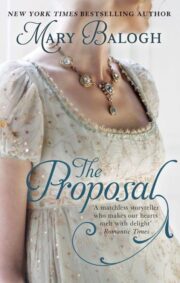

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.