“I thought you would not come,” he said. “I expected to open the carriage door to discover only Fiona and Constance and Philip within.”

“But I said I would come,” she said.

“I thought you would change your mind.”

“If I had done that,” she told him, “I would have let you know. I am a—”

Lady, she had been about to say. But he would have misinterpreted the word.

“Yes,” he said, “you are a lady.”

His fingertips were spread over the windowsill. He was looking out, not at her.

“Hugo,” she said, setting a hand lightly on his arm, “don’t make this a matter of class. If any of your family had changed their minds for some reason, they would have let you know. It is simple courtesy.”

“I thought you would not come,” he said. “I braced myself not to see you.”

What was he saying? Actually, it was pretty obvious what he was saying and Gwen slid her hand from his arm. Her heart seemed to be beating in her throat more than in her chest.

She looked back through the window.

“There is so much potentiality there,” she said.

“In the garden?” He turned his head briefly to look at her.

“The park is mainly flat as far as I could see when we were coming up the driveway,” she said. “But look, there is quite a dip beyond your flower patch. You could have a small lake down there if you wished. No, that would be too much. A large lily pond would be better, with tall ferns and reeds growing beyond it, between it and the trees. And the flower bed could be reshaped a little to curve down toward it with shrubs and taller flowers to the sides and shorter flowers and ground cover within and a path winding through it and a few seats to capture the view. There could be—”

She stopped abruptly and felt embarrassed.

“I do beg your pardon,” she said. “The flowers will be lovely when you have planted them. And the view is really not bad as it is. It is a country view. There is no sea in sight and no salt on the air. I far prefer the country inland. This is lovelier than Newbury.”

Strangely, she was not either lying or simply being polite.

“A lily pond,” he said, resting his elbows on the sill and gazing outward, eyes narrowed. “It would look grand. I have always thought of that dip in the land as an inconvenience. I have no imagination, you know. Not for things of the eye, anyway. I can enjoy them or criticize them when I see them, but I cannot imagine them. I can see all those paintings on the walls, for example, and know they are rubbish, but I cannot imagine the sorts of paintings with which I would replace them if I removed them all and consigned them to the rubbish heap. I would have to wander about galleries for the next ten years picking and choosing, and then perhaps nothing would match anything else, or else they would look all wrong in the rooms where I had decided to set them.”

“Sometimes,” she said, “having everything matching and symmetrical is no more pleasing to the eye or to the mind than barrenness. Sometimes you have to trust your intuition and go with what you like.”

“That is easy for you to say,” he said. “You can look out that window and see a lily pond and a curving flower garden and plants of different kinds and heights and seats from which to enjoy the view. All I see is a nice square patch of earth just waiting for flowers—if I just knew what flowers. And a troublesome dip of lawn beyond it and trees in the distance. I could not even think of a path on my own. Last year when all the flowers were blooming, I had to walk all around the edge of the bed to see them or else come up here to look down on them.”

“But what a glorious sight it must have been.” She set her hand on his arm again. “And sometimes one brief and glorious splash of color and beauty is enough for the soul, Hugo. Think of a fireworks display. There is nothing more brief and nothing more splendid.”

He turned his head at last and looked at her.

It was a long look, which she returned. She could not read his eyes.

“Welcome to my home, Gwendoline,” he said softly at last.

She swallowed and blinked several times. She smiled at him.

And wondrously, miraculously, he smiled back.

“I must go down,” he said, straightening up, “and meet everyone in the drawing room. You will come down when you are ready?”

“I will,” she said. “How will you explain my presence?”

“You have taken Constance under your wing,” he said, “and have enabled her to attend a few ton entertainments, as befits her status as my sister. My relatives are both amused by and impressed with my title, you know. But they are not unintelligent people. They will soon understand, if rumor has not already reached their ears, that you are here because I am courting you.”

“Are you?” she asked him. “The last time I saw you, you said quite definitely that you were not. I thought I was invited here to court you or at least to discover for myself why it is impossible for you to court me.”

He hesitated before answering.

“My relatives will conclude that I am courting you,” he said. “Everyone loves what appears to be a budding romance, especially when a family member is involved. Whether they are right or whether they are wrong remains to be seen.”

But perhaps his relatives would not love this particular budding romance, Gwen thought. They might well resent her. She did not say so aloud, though. She smiled again.

“I will be down soon,” she said.

He inclined his head to her and left the room. He closed the door quietly behind him.

Gwen stayed where she was for a short while. She thought back to the day on the beach in Cornwall when she had felt that tidal wave of loneliness. If she had not felt it then, would she have felt it ever? And, if she had not, would she have stayed safely cocooned in grief and guilt that had grown so muted that she had not even realized how they had paralyzed her life? Strangely, it had been a comfortable cocoon. She half wished she were still inside it, or that, if she must have been forced out, she had then proceeded to meet the quiet, comfortable, uncomplicated gentleman she had soon dreamed up—as if any such person really existed.

But she had met Hugo instead.

She shook her head slightly and made her way to the dressing room so that she could wash and change and have her hair freshly brushed before stepping fully into Hugo’s world.

Fiona’s parents were feeling somewhat overwhelmed, Hugo soon realized, and sat in a sort of huddle with their own family members. Even Fiona’s in-laws must seem like grand persons to them, and he knew they looked upon him in some awe.

Too late he realized he should have instructed his ever-resourceful butler to find someone to look after the two boys during the house party. They were sitting on a sofa with their parents, the younger squashed between the two of them, the elder on the other side of his father.

Hugo’s own relatives were boisterous, as they usually were in company with one another. But perhaps there was a little self-consciousness added today as they were in a strange place and there were other people present who were virtual strangers.

Fiona sat by the fireplace with Philip. Her mother was gazing wistfully at her.

Constance was flitting about from group to group, her arm through Gwendoline’s. She was introducing her to everyone as the lady who had presented her to the ton, the lady who was her sponsor. It was Hugo who ought to be making the introductions, but he was happy that Constance was doing it for him and unwittingly making it seem that indeed Gwendoline had been invited for her sake.

Ned Tucker stood behind the seated group of his friends from the grocery shop and looked good-humoredly about him. Hugo had wanted to invite him just to discover what, if anything, existed between him and Constance. And her grandmother had made it easy for him. When he had gone to the grocery shop to issue the invitation, Tucker had been with them, and Constance’s grandmother had laid a hand on his sleeve and told Hugo he was like one of the family. Hugo had promptly included him in the invitation.

And Hugo, observing the groups around him, realized that he was part of the scene too. He was standing there in the midst of it all, like a soldier on parade. He wished he had some social graces. He should have learned more while he was at Penderris. But he had never needed social graces to mingle with his family. He had never known a moment of self-consciousness or self-doubt when he was growing up among them. And he did not need social graces to mingle with Fiona’s family. He merely needed to show them that he was human, that in reality he was no different from them despite his title and wealth. Or perhaps that was what social graces were. There was Gwendoline, Constance’s arm still through hers, talking with Tucker, and all three of them laughed as Hugo watched them. Gwendoline did not have her nose in the air, as she had with him on occasion, and Tucker was not bobbing his head and tugging at his forelock. Hilda and Paul Crane got up from their seats and joined them, and then they were all laughing.

Hugo had the feeling he might be scowling. How was he to bring these separate groups together, make a relaxed house party out of it? Really, it had been a mad idea.

He was rescued by the arrival of the tea tray and another, larger one bearing all kinds of sumptuous looking goodies. He turned to his stepmother.

“Will you be so good as to pour, Fiona?” he asked.

“Of course, Hugo,” she said.

And it struck him that she was enjoying herself as a person of importance to everyone in the room, since as his stepmother she was in a sense his hostess. It had not occurred to him that he would need one. But of course he did. Someone had to pour the tea and sit at the foot of his dining table and stand at his side to greet the guests from the neighborhood when they arrived for the anniversary parties in a few days’ time.

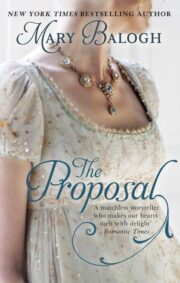

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.