She glared at his back, buoyed by hatred and determination. But he must go soon. He must go now. Please let him go now.

He did not go.

He lowered his hand from the knob and turned to face her.

“Let me show you what I mean,” he said.

She looked back at him, uncomprehending. Her hands were all pins and needles, she realized. She must have been clasping them too tightly.

“This has all been a one-way thing,” he said. “Right from the start. At Penderris you were in your own world, even if you did feel awkward at landing there uninvited. At Newbury Abbey you were in your own world and among your own family, not a single one of whom, I noticed, was without a title. Here you have been right in the center of your world—in this house, on the fashionable circuit in Hyde Park, at the Redfield House ball, at the garden party yesterday. I am the one each time who has been expected to step into a world that is not my own and prove myself worthy of it so that I can aspire to your hand. I have done that—repeatedly. And you criticize me for not feeling at home in it.”

“For feeling inferior,” she said.

“For feeling different,” he insisted. “Does there not seem something a bit unfair about it all?”

“Unfair?” She sighed. Perhaps he was right. She just wanted him to go and be done with it. He was going to go eventually anyway. It might as well be now. Her heart would be no less broken a week from now or a month.

“Come to my world,” he said.

“I have been to your house and met your sister and your stepmother,” she reminded him.

He looked steadily at her, without any relaxing of his expression.

“Come to my world,” he said again.

“How?” She frowned at him.

“If you want me, Gwendoline,” he said, “if you imagine that you love me and think you can spend your life with me, come to my world. You will find that wanting, even loving, is not enough.”

Her eyes wavered and she looked down at her hands. She stretched her fingers in an effort to rid them of the pins and needles. It was true. He had been the one to do all the adapting so far. And he had done well. Except that he was uncomfortable and unsure of himself and unhappy in a world that was not his own.

She would not ask how again. She did not know how. Probably he did not either.

“Very well,” she said, looking up again, glaring at him defiantly, almost with dislike. She did not want her comfortable world to be rocked more than it already had been by meeting and loving him.

Their eyes continued to do battle for a few silent moments. Then he bowed abruptly to her, and his hand came to rest on the knob of the door again.

“You will be hearing from me,” he said.

And he was gone.

While Gwen and Lily had been on Bond Street this morning, they had met Lord Merlock and had stood talking with him for a while before he offered to take them to a nearby tea shop for refreshments. Lily had been unable to accept. She had promised her children that she would be home in time for an early luncheon before they all went to the Tower of London with Neville. But Gwen had accepted. She had also accepted an invitation to share his box at the theater this evening with his four other guests.

She was still going to go. She was going to do her best to fall in love with him.

Oh, how absolutely absurd. As if one could fall in love at will. And how unfair to Lord Merlock if she were to flirt with him as a sort of balm to her own heartbreak without any regard whatsoever for his feelings. She would go as his guest, and she would smile and be amiable. Just that and no more.

How she wished, wished, wished she had not taken that walk along the pebbled beach after her quarrel with Vera. And how she wished that having done so, she had chosen to return by the same route. Or that she had climbed the slope with greater care. Or that Hugo had not chosen that morning to go down onto the beach himself and then to sit up on that ledge just waiting for her to come along and sprain her ankle.

But such wishes were as pointless as wishing the sun had not risen this morning or that she had not been born.

Actually, she would hate not to have been born.

Oh, Hugo, she thought as she picked up her embroidery again and looked in despair at the lovely silky green petal of her pink rose.

Oh, Hugo.

Gwen neither saw nor heard from Hugo for a week. It felt like a year even though she filled every moment of every day with busy activity and sparkled and laughed in company more than she had done in years.

She acquired a new beau—Lord Ruffles, who had raked his way through young manhood and early middle age and had arrived at a stage of life perilously close to old age before deciding that it was high time to turn respectable and woo the loveliest lady in the land. That was the story he told Gwen, anyway, when he danced with her at the Rosthorn ball. And when she laughed and told him that he had better not waste any more time, then, in finding that lady, he set one slightly arthritic hand over his heart, gazed soulfully into her eyes, and informed her that it was done. He was her devoted slave.

He was witty and amusing and still bore traces of his youthful good looks—and he had no more interest in settling down, Gwen guessed, than he had in flying to the moon. She allowed him to flirt outrageously with her wherever they met during that week, and she flirted right back, knowing that she would not be taken seriously. She enjoyed herself enormously.

She took Constance Emes with her almost everywhere she went. She genuinely liked the girl, and it was refreshing to watch her enjoy the events of the Season with such open, innocent pleasure. She had acquired a sizable court of admirers, all of whom she treated with courtesy and kindness. She surprised Gwen one day, though.

“Mr. Rigby called this morning,” she said at the Rosthorn ball. “He came to offer for me.”

“And?” Gwen looked at her with interest and fanned her face against the heat of the ballroom.

“Oh, I refused him,” Constance said as if it were a foregone conclusion. “I hope I did not hurt him. I do not believe I did, however, though he was understandably disappointed.”

She said it without any conceit.

“I believe,” the girl added, “his pockets are rather to let, poor gentleman.”

“He would have been a very good match for you nevertheless,” Gwen said. “His grandfather on his mother’s side was a viscount. He is handsome and personable. He would have treated you well, I believe. But if you do not feel any deep affection for him, then none of those things matter and I can only congratulate you for having the courage to refuse your first offer.”

“If he had no money,” Constance said, “he might have some relative purchase a commission in the military for him or become a clergyman. Both are considered quite unexceptionable careers for the upper classes. He might be someone’s steward or secretary with only a little lowering of his pride. Marrying a rich wife is not his only option.”

“And that is what he was trying to do with you?” Gwen asked. “Did he admit as much?”

“He did when I pressed him,” Constance said. “And he was hardly embarrassed at all. He assured me that we had equal assets to bring to a marriage—money on my part, lineage and social standing on his. And he assured me, I believe truthfully, that he had an affection for me.”

“But you were not convinced it was an equal exchange?” Gwen asked.

The girl frowned and unfurled her own fan.

“Oh, I suppose it was,” she admitted. “But what would he do for the rest of his life, Lady Muir? He would have all my money with which to be idle, but … why? Why would any man choose to be idle?”

Gwen laughed.

“Mr. Grattin is coming to claim his set with you,” she said.

The girl smiled brightly at her approaching partner.

She had not mentioned Hugo. She did not mention him all week, and Gwen did not ask.

You will be hearing from me, he had said the last time she saw him. And she had expected to hear the next day or the day after.

More fool she.

And then she did hear. He sent a letter, which was beside her plate at breakfast one morning with a bundle of invitations.

“Constance’s grandparents will be celebrating the fortieth anniversary of their marriage in two weeks’ time,” he wrote. “These are my stepmother’s parents, the grocery shop owners. A cousin on my father’s side and his wife will be celebrating their twentieth a few days later. Both sides of the family have agreed to spend five days with me at Crosslands Park in Hampshire in order to celebrate the occasions. If you would care to join us, you may travel in the carriage with my stepmother and sister.”

There was no opening greeting, no personal message, no specific dates given, and no assurance at the end that he was her very obedient servant or any such courtesy. Just his signature, boldly scrawled but without any affectation. It was perfectly legible.

“Trentham.”

Gwen smiled ruefully down at the single sheet of paper.

Come to my world.

“Is it a joke you are able to share, Gwen?” Neville asked from his place at the head of the table.

“I have been invited to a five-day house party in the country in the middle of the Season,” she said.

“Oh, how lovely,” Lily said. “Whose?”

“Lord Trentham’s,” she said. “It is in celebration of two wedding anniversaries, one on his father’s side of the family and one on his stepmother’s. Both families will be there, at Crosslands Park in Hampshire, that is. And me if I care to go.”

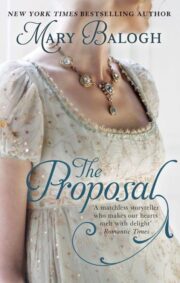

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.