“I am probably depriving you of the pleasure of performing your favorite dance,” he said.

He was.

“I believe,” she said, “I will enjoy strolling with you more than I would waltzing with someone else, Lord Trentham.”

Unwise words indeed. She had not planned them. She was not a flirt. Or never had been, anyway. She had spoken the simple truth. But sometimes truths, even simple ones, were best kept to oneself.

He offered his arm and she slipped her hand through it. He led her across the floor and out onto the deserted balcony and down the steep steps to the equally deserted garden below. It was not totally dark, however. Small colored lanterns swung from tree branches and lit the graveled walks that meandered through flower beds bordered by low box hedges.

From the ballroom above came the strains of a lilting waltz.

“I must thank you,” he said stiffly, “for what you have done and are doing for Constance. I do not believe she could possibly be happier than she is tonight.”

“But I have been at least partly selfish,” she said. “Sponsoring her has given me great pleasure. And we have, I am afraid, spent a great deal of your money.”

“My father’s money,” he said. “Her father’s money. But will she be as unhappy in the near future as she is happy now? She surely cannot expect many more invitations to balls or other events, and she surely cannot expect any of the gentlemen dancing with her tonight to dance with her again. Her mother, Lady Muir, is sitting at home with her mother and sister. They make a modest living from a small grocery shop and hardly qualify even as middle-class people.”

“And she is the sister of Lord Trentham of Badajoz fame,” she said.

He turned his head to look at her in the near darkness.

“You probably have not even noticed that the ballroom is buzzing with your fame,” she said. “For years people have waited for some glimpse of you, and suddenly here you are. Some factors transcend class lines, Lord Trentham, and this is one of them. You are a hero of almost mythic proportions, and Constance is your sister.”

“That is the daftest thing I have ever heard in my life,” he said. “It is that drawing room at Newbury Abbey all over again.”

“And for your own part,” she said, “I suppose it would be enough to send you scurrying back to the country and your lambs and cabbages. But you cannot scurry, for you have your sister’s happiness to consider. And her happiness is of greater importance to you than your own.”

“Who says so?” he asked her, scowling.

“You have said so by your actions,” she said. “You have never needed to put it into words, you know, though you have come close on occasion.”

“Damnation,” he said. “God damn it all.”

Gwen smiled and waited for an apology for the shocking language. None came.

“Besides,” she said, “even apart from your fame, rumor is also making the rounds that Miss Emes is quite fabulously wealthy. A pretty and genteel young lady who is properly chaperoned will arouse interest anywhere, Lord Trentham. When she is also richly dowered, she is quite irresistible.”

He sighed.

There was a wooden seat at the far end of the garden beneath the shade of an old oak tree. It faced across the flower beds toward the lighted house. They sat down side by side, and for a few moments there was silence again. She would not be the one to break it, Gwen decided.

“I am supposed to be courting you,” he said abruptly.

She turned her head to look at him, but his face was in shadow.

“Not supposed to,” she said, “only invited if you wish to do so. And with no promise that your courtship will be favorably received.”

“I am not sure I do wish to,” he said.

Well. Blunt speaking as usual. She should be relieved, Gwen thought. But her heart seemed to have sunk down to the soles of her dancing slippers.

“I don’t think I want to court a murderess,” he said, “if that is what you are. Though why I should object, I do not know, since I could myself be accused of multiple murders without too much of a stretching of the truth. And I have entrusted my sister to your care.”

Well. So much for romance and light conversation suited to the festive occasion of a ball during the Season.

He had no more to say. There were a few more moments of silence between them. This time she was going to have to break it.

“I did not literally kill Vernon,” she said. “Neither did Jason. But I feel as if we both did. I feel that we caused his death, anyway. Or that I did. And my conscience will always be heavy with guilt. You would indeed do well not to court me, Lord Trentham. You carry around enough guilt of your own without having your soul darkened with mine. We both need someone to lift us free of such heaviness.”

“No one can do that for you,” he said. “Never marry with that hope. It will be dashed before a fortnight has passed.”

Gwen swallowed and smoothed her fan over her lap. She could see the shadows of dancers through the French windows in the distance. She could hear music and laughter. People without a care in the world.

A naïve assumption. Everyone had a care in the world.

“Jason was visiting, as he often did when he had leave,” she said. “I hated those visits as much as Vernon loved them. I hated him, though I could never explain quite why. He seemed fond enough of my husband and concerned about him. Though he did go too far at the end. Vernon was in the depths of one of his blackest moods and he had gone to bed early one night. He had excused himself from the dining table, leaving Jason and me together. How we ended up out in the hall talking instead of being still in the dining room I cannot remember, but that is where we were.”

It was a marbled hall, cold, hard, echoing, beautiful in a purely architectural sense.

“Jason thought Vernon should be committed to some sort of institution,” she said. “He knew of a place where he would get good care and where, with a bit of firm, expert handling, he would learn to pull himself together and get over the loss of a child who had never even been born. Vernon had always been a bit weak emotionally, he said, but he could be toughened up with the proper training. In the meantime, Jason would take a longer leave and manage the estate so that Vernon would be free of worry while he recovered his spirits and learned how to strengthen his mind. The army would have been good for him, he said, but that had always been out of the question because Vernon had succeeded to the title when he was fourteen. Even so, his guardians ought not to have been so soft with him.”

Gwen spread her fan across her lap, but in the darkness she could not see the delicate flowers painted there.

“I told him,” she said, “that no one was putting my husband in any institution. He was sick, but he was not insane. No one was going to handle him, firmly or expertly or any other way. And no one was going to strengthen his character. He was sick and he was sensitive, and I would nurse him and coax him into more cheerful spirits. And if he never got better, then so be it.”

She closed the fan with a snap.

“He had not gone to bed,” she said. “He was standing up in the gallery, without a light, looking down at us and listening to every word. We only knew he was there when he spoke. I can remember every word. My God, he said, I am not insane, Jason. You cannot believe I am mad. Jason looked up at him and told him quite bluntly that he was. And Vernon looked at me and said, I am not sick, Gwen. Or weak. You cannot think that. You cannot think that I need nursing or humoring. And that was when I killed him.”

Her fan was shaking on her lap. She realized that it was her hands that were shaking only when a large, warm, steady hand covered them both.

“Not now, Vernon, I said to him. I am weary. I am mortally weary. And I turned to walk to the library. I needed to be alone. I was very upset at what Jason had suggested, and I was even more upset that Vernon had overheard. I felt that a crisis point had been reached, and I was in no frame of mind to deal with it. I had my hand on the doorknob when he called my name. Ah, the anguish in his voice, the sense of betrayal. All in that one word, my name. I was turning back to him when he threw himself over the balustrade, and so I saw it from start to finish. I suppose it lasted for a second, though it seemed an eternity. Jason had his arms raised toward him as if to catch him, but it could not be done, of course. Vernon was dead before I could open my mouth or Jason could move. I do not believe I even screamed.”

There was a rather lengthy silence. Gwen frowned, remembering, something she almost never allowed herself to do of those moments. Remembering that there had been something puzzling, something … off. Even at the time her mind had not been able to grasp what it was. It was impossible to do so now.

“You did not kill him,” Lord Trentham said. “You know very well you did not. Depressed though Muir was, he nevertheless made the deliberate decision to hurl himself to his death. Even Grayson did not kill him. Yet I understand why you feel guilty, why you always will. I understand.”

It felt strangely like a benediction.

“Yes,” she said, “you of all people would know how guilt where there is no real blame can be almost worse than guilt where there is. There is no atonement to be made.”

“Stanbrook once told me,” he said, “that suicide is the worst kind of selfishness, as it is often a plea to specific people who are left stranded in the land of the living, unable for all eternity to answer the plea. Your case is similar in many ways to his. For one moment you were unable to cope with the constant and gargantuan task of caring for your husband’s needs, and for that momentary lapse he punished you for all time.”

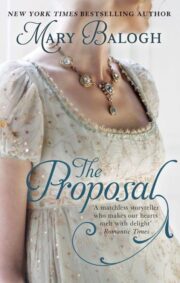

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.