“I shall go to the kitchen myself, Fee, as soon as Constance and Hugo have gone, and make some soup,” Fiona’s mother was saying when Hugo came into the room. “There is nothing better to coax an invalid back to health than good, hot soup. Oh, my!”

She had spied Hugo.

He made conversation, but only for a few minutes. Constance was not about to risk being late for her first ball. She burst in upon them, looking as if she were literally about to burst, and then stood inside the sitting room door, blushing and selfconscious and biting her lower lip.

“Oh, my!” her grandmother said again.

Like a bride, she had not allowed anyone to see the gown she would wear tonight or even to know anything about it. She was all white from head to toe. But there was nothing bland about her appearance, Hugo decided, despite the fact that even her hair was blond. She shimmered in the lamplight. He was no expert on clothing, especially women’s, but he could see that there were two layers to her gown, the inside one silky, the outer one lacy. It was high at the waist, low at the bosom, and youthful and pretty and perfect. She had white slippers, white gloves, a silver fan, and white ribbons threaded through her curls.

“You look as pretty as a picture, Connie,” he said with no originality at all.

She turned her head to beam at him—and her grandmother wailed and spread a large cotton handkerchief over her eyes.

“Oh,” she cried, “you look like your mama all over again, Constance. You look like a princess. Doesn’t she, Hilda, my love?”

Her younger daughter, thus appealed to, agreed with a smile after setting down her crochet in her lap.

“Constance.” Her mother reached out a pale hand toward her. “Your father would advise you not to forget your roots. I would advise you to do whatever will make you happy.”

It was a remarkable pronouncement coming from Fiona. Constance took her hand and held it to her cheek for a moment.

“You do not mind my going, Mama?” she asked.

“Your grandmother is going to make me soup,” Fiona said. “She always made the very best soup in the world.”

Five minutes later Hugo and his sister were in his traveling carriage, on their way to Hanover Square.

“Hugo,” she said, setting one gloved hand in his, “you are like a rock of stability. I am so frightened that I am sure my chattering teeth will drown out the sound of the orchestra when I get there and everyone will frown at me and Lady Ravensberg will accuse me of ruining her ball. Of course, you do not have to be afraid. You are Lord Trentham. My grandparents are shopkeepers. Is not Grandmama a dear, though? And Aunt Hilda has eyes that twinkle kindly when she talks. I like her. And I still have my grandpapa and my uncle and aunt and cousins to meet—and Mr. Crane, Aunt Hilda’s betrothed. I have a whole other family, as well as Mama and you and all Papa’s relatives, even if they are only shopkeepers. That does not matter, does it? Papa always used to say that no one, not even the lowliest crossing sweeper, ought to be ashamed of who he is. Or she. I always used to tell him that—or she, Papa, I used to say, and he would laugh and say it back to me. I think Mama is happy to see Grandmama, don’t you? And I think she is getting better again. Do you think—Oh, I am prattling. I never prattle. But I am terrified.” She laughed softly.

He squeezed her hand and concentrated upon being like a rock of stability. If she only knew!

They were unable to drive up to the grand, brightly lit mansion on Hanover Square and disappear indoors to find some shadowed corner in which to hide. There was a line of carriages, and they had to await their turn. And when it was their turn, they had to allow a grandly liveried footman to open the carriage door, and they had to step down onto a red carpet, which extended from the edge of the pavement all the way up the steps of the house.

And when they stepped into the house at last, they found themselves in a large, high-ceilinged hall beneath the bright lights of a large candelabrum and in the midst of a chattering throng of gorgeously clad ladies and gentlemen. Hugo, glancing around, discovered without surprise that he did not know a blessed one of them. But at least Grayson was not among them.

“We will go on up, then, Connie,” he said to his silent sister, his voice sounding to his own ears remarkably like that of Captain Emes ordering his subordinate officers to form the battle lines.

But the broad staircase, which presumably led up to the ballroom, was no better than the hall. It was just as brightly lit, and it was crowded with chattering, laughing people who were awaiting their turn, Hugo soon realized, to be announced prior to passing along the receiving line.

Oh, good Lord, give him two Forlorn Hopes.

“Not too much longer now,” he said with hearty jocularity, patting his sister’s cold, clinging hand.

“Hugo,” she whispered, “I am here. I am really here.”

And he looked down at her and realized that it was excitement and brimming happiness that she was really feeling. And he had been toying with the ignominious idea of suggesting that they flee.

“I do believe you are right,” he said, and smiled at her.

And then they were at the top of the stairs, and a stiffly formal majordomo, who reminded Hugo of Stanbrook’s butler, bent an ear to hear their identities, and announced them in loud, firm tones.

“Lord Trentham and Miss Emes.”

The receiving line was made up of four persons, Viscount and Viscountess Ravensberg, whom Hugo remembered from the drawing room at Newbury Abbey, and the Earl and Countess of Redford, who must be Ravensberg’s parents. He bowed. Constance curtsied. Greetings and pleasantries were exchanged. Lady Ravensberg admired Constance’s dress and actually winked at her. She looked assessingly at him and did not wink. It was all surprisingly easy. But then the aristocracy were adept at making such occasions easy. They knew how to make small talk, the hardest talk in the world to make in Hugo’s experience.

They stepped into the ballroom. Hugo had a quick impression of vast size, of hundreds of candles burning in candelabra overhead and in wall sconces about the perimeter, of banks of flowers and a gleaming wooden floor, of mirrors and pillars, of the flower of the ton dressed in all its finery and wearing all its most costly jewels. For Constance the impression was more than momentary. Hugo heard her gasp and saw her turn her head from side to side and up and down as though she could never get enough of a look at her very first ton ballroom at her very first ton ball.

But it was a very small piece of the scene that soon riveted Hugo’s attention. Lady Muir was coming to meet them.

She was dressed in pale spring green again. The fabric of her gown—silk? satin?—gleamed and glittered in the candlelight. It skimmed the curves of her body, revealing a delicious amount of bosom and a tantalizing suggestion of shapely legs—even if one was shorter than the other. Her gloves and slippers were a dull gold. She wore a simple gold chain with a small diamond pendant about her neck, and gold and diamonds winked from her earlobes beneath her hair. An ivory fan dangled from one of her wrists.

She was all that was beautiful and desirable—and unattainable. How could he have had the effrontery to make her an offer of marriage not so long ago? Yet he had once possessed that exquisitely gorgeous body. And after refusing his offer, she had invited him to court her.

Did he dare? Did he even want to? And exactly how many times had he asked himself those questions?

She was smiling—at his sister.

“Miss Emes—Constance,” she said, “you look absolutely delightful. Oh, I would not be at all surprised if you dance every set and even have to turn prospective partners away. Fortunately this is not anyone’s come-out ball, so all the focus of attention will not be upon any other young lady in particular. Come.” And she held out her arm for Constance to take.

She did glance at Hugo then, after Constance had linked an arm through hers. And Hugo had the satisfaction of seeing the color deepen in her cheeks. She was not quite indifferent to him, then.

“Lord Trentham,” she said, “you may mingle with the other guests if you wish or even withdraw to the card room. Your sister will be quite safe with me.”

He was being dismissed. To mingle. That simple activity. But with whom, pray? It would be a bit ridiculous to panic, however. She had mentioned a card room. He could go and hide himself in there. But before he went, he wanted to see Constance dance her first set at a ton ball. He could trust Lady Muir to see to it that she did dance and that it would be with someone respectable.

He spoke before she whisked Constance away into the crowds.

“I hope, Lady Muir,” he said, “you will yourself be dancing tonight. And that you will save a set for me.”

She did dance despite her limp. She had told him so at Pen-derris.

“Thank you,” she said, and he was interested to note that she sounded almost breathless. “The fourth set is to be a waltz. It is the supper dance.”

Oh, Lord. A waltz. The vicar’s wife and a few of the other village ladies had undertaken the gargantuan task of teaching him the steps at an assembly eighteen months or so ago, amid much laughter and teasing from them and every other mortal gathered there for the occasion. He had ended up actually dancing it with the apothecary’s wife at the end of the assembly, to much applause and more laughter. The best that could be said was that he had not once trodden upon the good lady’s toes.

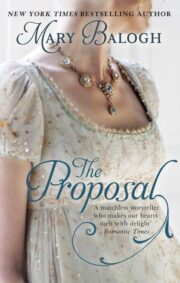

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.