“Lady Muir,” he said, clutching his crossed fingers almost to the point of pain, “will you marry me?”

Plowing onward when one had not scouted out the territory ahead could be disastrous. He knew that from experience. He knew it now again. All the words he had spoken seemed laid out before him as though printed on a page, and he could see with painful clarity how wrong they were.

And even without that imagined page, there was her face.

It looked as it had that very first day, when she had hurt her leg.

Coldly haughty.

“Thank you, Lord Trentham,” she said, “but I beg to decline.”

Well, there. That was it.

She would have refused him no matter how he had worded his proposal. But he really had not needed to make such a mull of it.

He stared at her, unconsciously hardening his jaw and deepening his frown.

“Of course,” he said. “I expected no different.”

She gazed at him, that haughty look gradually softening into one of puzzlement.

“Did you really expect me to marry you merely because your sister wishes to attend a ton ball?” she asked.

“No,” he said.

“Why did you come, then?” she asked.

Because I was hoping you were with child. But that was not strictly true. He had not been hoping.

Because I have not been able to get you out of my mind. Pride prevented him from saying any such thing.

Because we had good sex together. No. It was true, but it was not the reason he was here. Not the only reason, anyway.

Why was he here, then? It alarmed him that he did not know the answer to his own question.

“There is no other reason than that, is there?” she asked softly after a lengthy silence.

He had uncrossed his fingers and dropped his arms to his sides. He flexed his fingers now to rid them of the pins and needles.

“I had sex with you,” he said.

“And there were no consequences,” she said. “You did not force me. I freely consented, and it was very … pleasant. But that was all, Hugo. It is forgotten.”

She had called him Hugo. His eyes narrowed on her.

“You said at the time,” he said, “that it was far more than just pleasant.”

Her cheeks flushed.

“I cannot remember,” she said. “You are probably right.”

She could not possibly have forgotten. He was not conceited about his own prowess, but she had been a widow and celibate for seven years. She would not have forgotten even if his performance had been miserable.

It did not matter, though, did it? She would not marry him even if he groveled on the floor at her feet, weeping and reciting bad poetry. She was Lady Muir and he was an upstart. She had had a bad experience with her first marriage and would be very wary about undertaking another. He was a man with issues. She was well aware of that. He was large and clumsy and ugly. Well, perhaps that was a bit of an exaggeration, but not much.

He bowed abruptly to her.

“I thank you, ma’am,” he said, “for granting me a hearing. I will not keep you any longer.”

She turned to leave, but she paused with her hand on the knob of the door.

“Lord Trentham,” she said without turning around, “was your sister your only reason for coming here?”

It would be best not to answer. Or to answer with a lie. It would be best to end this farce as soon as possible so that he could get back out into the fresh air and begin licking his wounds again.

So of course he spoke the truth.

“No,” he said.

Gwen had been feeling angry and so sad that she hardly knew how to draw one breath to follow another. She had felt insulted and grieved. She had longed to make her escape from the library and the house, to dash through the rain to the dower house in her overlong dress and on her weak ankle.

But even the dower house would not have been far enough. Even the ends of the world would not have been.

He had looked like a stern, dour military officer when she came into the library. Like a cold, hard stranger who was here against his will. It had been almost impossible to believe that on one glorious afternoon he had also been her lover.

Impossible with her body and her rational mind, anyway.

Her emotions were a different matter.

And then he had announced that he had come—as if she must have been expecting him, longing for him, pining for him. As though he were conferring a great favor on her.

And then. Well, he had not even made any attempt to hide the motive behind his coming to offer her marriage. It was so that she would use her influence to introduce his precious sister to the ton and find a man of gentle birth to marry her.

He must have been hoping that she was with child so that his task would have been made easier.

She stood with her hand on the door after he had dismissed her—he had dismissed her from Neville’s library. She was that close to freedom and to what she knew would be a foolish and terrible heartbreak. For she could no longer like him, and her memories of him would be forever sullied.

And then it occurred to her.

He could not possibly have come here with the intention of telling her that his sister needed an invitation to a ton ball and that therefore she must marry him. It was just too absurd.

It was altogether possible that he would look back upon this scene and the words he had spoken and cringe. She guessed that if he had rehearsed what he would say, the whole speech had fled from his mind as soon as she stepped into the room. It was altogether possible that his stiff military bearing and hard-set jaw and scowl were hiding embarrassment and insecurity.

It had, she supposed, taken some courage to come here to Newbury.

She could be entirely wrong, of course.

“Lord Trentham,” she asked the door panel in front of her face, “was your sister your only reason for coming here?”

She thought he was not going to answer. She closed her eyes, and her right hand began to turn the knob of the door. The rain pelted against the library window with a particularly vicious burst.

“No,” he said, and she relaxed her hold on the doorknob, opened her eyes, drew a slow breath, and turned.

He looked the same as before. If anything, his scowl was even more fierce. He looked dangerous—but she knew he was not. He was not a dangerous man, though there must be hundreds of men, both living and dead, who would disagree with her if they could.

“I had sex with you,” he said.

He had said that before, and then they had got distracted by a discussion of whether she had found it pleasant or more than pleasant.

“And that means you ought to marry me?” she said.

“Yes.” He gazed steadily at her.

“Is this your middle-class morality speaking?” she asked him. “But you have had other women. You admitted as much to me at Penderris. Did you feel obliged to offer them marriage too?”

“That was different,” he said.

“How?”

“Sex with them was a business arrangement,” he said. “I paid, they provided.”

Oh, goodness. Gwen felt dizzy for a moment. Her brother and her male cousins would have forty fits apiece if they were listening now.

“If you had paid me,” she said, “you would not be obliged to offer me marriage?”

“That’s daft,” he said.

Gwen sighed and looked toward the fireplace. There was a fire burning, but it needed more coal. She shivered slightly. She ought to have asked Lily for a shawl to wrap about her shoulders.

“You are cold,” Lord Trentham said, and he too looked at the fireplace before striding over to the hearth and bending to the coal scuttle.

Gwen moved across the room while he was busy and sat on the edge of a leather chair close to the blaze. She held her hands out to it. Lord Trentham stood slightly to one side of the fire, his back to it, and looked down at her.

“I never felt any strong urge to marry,” he said. “I felt it even less after my years at Penderris. I wanted—I needed to be alone. It is only during the past year that I have come reluctantly to the conclusion that I ought to marry—someone of my own kind, someone who can satisfy my basic needs, someone who can manage my home and help in some way with the farm and garden, someone who can help me with Constance until she is properly settled. Someone to fit in, not to intrude. Someone on whose private life I would not intrude. A comfortable companion.”

“But a lusty bed partner,” she said. She glanced up at him before returning her gaze to the fire.

“And that too,” he agreed. “All men need a vigorous and satisfying sex life. I do not apologize for wanting it within a marriage rather than outside it.”

Gwen raised her eyebrows. Well, she had started it.

“When I met you,” he said, “I wanted to bed you almost from the beginning even though you irritated me no end with your haughty pride and your insistence upon being put down when I was carrying you up from the beach. And I expected to despise you after you told me about that ride with your husband and its consequences. But we all do things in our lives that are against our better judgment and that we regret bitterly forever after. We all suffer. I wanted you, and I had you down in that cove. But there was never any question of marriage. We were both agreed upon that. I could never fit in with your life, and you could never fit in with mine.”

“But you changed your mind,” she said. “You came here.”

“I somehow expected,” he said, “that you were with child. Or if I did not exactly expect it, I did at least shape my mind in that direction so that I would be prepared. And when I did not hear from you, I thought that perhaps you would withhold the truth from me and bear a bastard child I would never know anything about. It gnawed at me. I wouldn’t have come even then, though. If you were so much against marrying me that you would even hide a bastard child from me, then coming here and asking was not going to make any difference. And then Constance told me about her dreams. Youthful dreams are precious things. They ought not to be dashed as foolish and unrealistic just because they are young dreams. Innocence ought not to be destroyed from any callous conviction that a realistic sort of cynicism is better.”

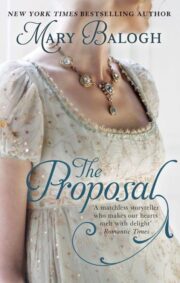

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.