A sudden quiet descended upon the drawing room when they entered it. Neville was over by the window, frowning. Everyone else was present. Except Hugo.

Lily noticed his absence too.

“Oh, has Lord Trentham left?” she asked. “But we were as quick as we could be. Poor Gwen was soaked through to the skin.”

He had left? After coming all this way to inquire about her ankle?

“He is in the library,” Neville said. “I just left him there. He wants a private word with Gwen.”

The hush seemed to intensify.

“It really is quite extraordinary,” their mother said, breaking it. “Lord Trentham is not at all the sort of man whose attentions you would ever dream of encouraging, Gwen. But he has come to offer for you nevertheless.”

“I consider it quite unpardonably presumptuous of him, Gwen,” Wilma, Countess of Sutton, said, “even if he did do you a considerable service when you were in Cornwall. I daresay the title and the accolades that followed upon his undoubtedly heroic act have gone to his head and given him ideas above his station.”

Wilma had never been Gwen’s favorite cousin. Sometimes it was hard to believe that she could possibly be Joseph’s sister.

“I did not feel I had the right to speak for you, I am sorry, Gwen,” Neville said. “You are thirty-two years old. I do not believe the offer is quite as impertinent as Wilma suggests, though. Trentham does have the title, after all, and he has the wealth to go with it. And he certainly is a great hero, perhaps the greatest of the recent wars. He could probably be the darling of polite society if he so chose—as our reaction to meeting him here a while ago would attest. It is perhaps to his credit that he has never sought fame or adulation and that he looked a little uncomfortable with them this afternoon. But his coming here to offer you marriage is a little embarrassing for you. I am sorry I could not merely send him away. I did, however, warn him that you have worn the willow for Muir quite constantly for seven years and are unlikely to give him the answer for which he hopes.”

“It is as well you did not try to speak for Gwen, Neville,” Joseph, Marquess of Attingsborough, said, grinning at Gwen. “Women do not like that, you know. I have it on Claudia’s authority that they are quite capable of speaking up for themselves.”

Claudia was his wife.

“That is all very well, Joseph,” Wilma said, “when it is a gentleman to whom she is to address herself.”

“Oh, come now, Wilma,” Lauren said. “Lord Trentham seemed a perfect gentleman to me.”

“Poor Lord Trentham will be sending down roots into the library carpet,” Lily said, “or else wearing a path threadbare across it. We had better let Gwen go and speak to him herself. Go, Gwen.”

“I shall do so,” Gwen said. “You must not concern yourself, though, Mama. Or you, Nev. Or any of you. I will not be marrying a blunt soldier of the lower classes, even if he is a hero.”

She was surprised to hear some bitterness in her voice.

No one replied even though Elizabeth, Duchess of Portfrey, her aunt, was smiling at her and Claudia was nodding briskly in her direction. Her mother was gazing down at the hands in her lap. Neville was looking slightly reproachful. Lily was looking troubled. Lauren had an arrested expression on her face.

Gwen left the room and made her way down the stairs, holding up her skirt carefully so that she would not trip over the hem.

She had still not fully tested her reaction to finding Hugo here. She knew now why he had come. But why? The fact that they could never marry each other had always been something upon which they were both agreed.

Why had he changed his mind?

She would, of course, say no. Being in love with a man was one thing—even making love with him. Marrying him was another thing entirely. Marriage was about far more than just loving and making love.

She nodded to the footman who was waiting to open the library door for her.

Chapter 12

With every mile of his journey to Newbury Abbey, Hugo had asked himself what he thought he was doing. With every mile he had tried to persuade himself to turn back before he made a complete ass of himself.

But what if she was with child?

He had kept on going.

The more fool he. There had been that excruciatingly embarrassing fifteen minutes or so in the drawing room. And that had been followed by an equally embarrassing interview with Kilbourne in the library.

Kilbourne had been perfectly polite, even friendly. But he had clearly thought Hugo daft in the head for coming here and expecting that Lady Muir would listen favorably to his marriage offer. He had looked slightly embarrassed and had all but told Hugo that she would not have him. She had loved her first husband dearly, he had explained, and had been inconsolable at his death. She had vowed never to marry again, and she had never yet shown any sign of changing her mind about that. Hugo must not take it personally if she refused. He had almost said when she refused. His lips had formed the word and then corrected themselves so that he could say if instead.

Hugo was still in the library—alone. Kilbourne had gone back up to the drawing room, promising that he would send his sister down as soon as she appeared there herself.

Perhaps she would not come down. Perhaps she would send Kilbourne back with her answer. Perhaps he was about to come face to face with the greatest humiliation of his life.

And serve him right too. What the devil was he doing here?

He had done nothing to help his own cause either, he remembered with a grimace. The only thing she had had to say when he had seen her earlier was that she looked like a drowned rat. And he, suave and polished gentleman that he was, had agreed with her. He might have added that she looked gorgeous anyway, but he had not done so and it was too late now.

A drowned rat. A fine thing to say to the woman to whom one had come to offer marriage.

He thought the library door would never open again, but that he would be left to live out the rest of his life rooted to the spot on the library carpet, afraid to move a muscle lest the house fall about his shoulders. He deliberately shrugged them and shuffled his feet just to prove to himself that it could be done.

And then the door did open when he was least expecting it, and she stepped inside. An unseen hand closed the door from the other side, but she leaned back against it, her hands behind her, probably gripping the handle. As though she were preparing to flee at the first moment she felt threatened.

Hugo frowned.

Her borrowed dress was too big for her. It completely covered her feet and was a little loose at the waist and hips. But the color suited her, and so did the simplicity of the design. It emphasized the trim perfection of her figure. Her blond hair was curlier than usual. The damp must have got to it despite the bonnet she had worn and the umbrella she had held as she came hurtling up across the lawn. Her cheeks were flushed, her blue eyes wide, her lips slightly parted.

Like a foolish schoolboy, he crossed both sets of fingers on each hand behind his back and even the thumbs of his two hands.

“I came,” he said.

Good Lord! If there were an orator-of-the-year award, he would be in dire danger of winning it.

She said nothing, which was hardly surprising.

He cleared his throat.

“You did not write,” he said.

“No.”

He waited.

“No,” she said again. “There was no need. I told you there would not be.”

He was ridiculously disappointed.

“Good.” He nodded curtly.

And silence descended. Why was it that silence sometimes felt like a physical thing with a weight of its own? Not that there was real silence. He could hear the rain lashing down against the window panes.

“My sister is nineteen,” he said. “She has never had much of a social life. My father used to take her to visit our relatives when he was still alive, but since then she has remained essentially at home with her mother, who is always ailing and likes to keep Constance by her side. I am now her guardian—my sister’s, that is. And she needs a social life beyond mere family.”

“I know,” she said. “You explained this to me at Penderris. It is one of your reasons for wanting to marry a woman of your own kind. A practical, capable woman, I believe you said.”

“But she—Constance—is not content to meet her own kind,” he said. “If she were, all would be well. Our relatives would take her about with them and introduce her to all kinds of eligible men, and I would not need to marry after all. Not for that reason, anyway.”

“But—?” She made a question of it.

“She has her heart set upon attending at least one ton ball,” he said. “She believes my title will make it possible. I have promised her that I will make it happen.”

“You are Lord Trentham,” she said, “and the hero of Badajoz. Of course you can make it happen. You have connections.”

“All of them men.” He grimaced slightly. “What if one ball is not enough? What if she is invited elsewhere after that first? What if she acquires a beau?”

“It is altogether possible that she will,” she said. “Your father was very wealthy, you told me. Is she pretty?”

“Yes,” he said. He licked his lips. “I need a wife. A woman who is accustomed to the life of the beau monde. A lady.”

There was a short silence again, and Hugo wished he had rehearsed what he would say. He had the feeling that he had gone about this all wrong. But it was too late now to start again. He could only plow onward.

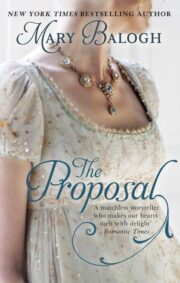

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.