He went back for her half an hour later, after informing Ben that he was taking her out for a drive and gathering the things they would need to take with them—a blanket for her to sit on, cushions for her back and her foot, and, as an afterthought, a large towel. He had also gone to the stables and carriage house and hitched a horse to the gig and brought it around to the front doors.

This, he thought, was not a good idea. But he was committed now. And he could not feel quite as sorry as he knew he ought. It was a lovely day. A man needed company when the sun shone and there was warmth in the air. Not that he had ever before entertained such a daft thought. Why would a sunny day make a man feel lonelier than he felt on a cloudy day?

He carried Lady Muir back downstairs and settled her in the gig before taking his place beside her. He gathered the ribbons in his hands and gave the horse the signal to start.

Spring was her favorite season, she had told him two days ago, full of newness and hope. Somehow today he could understand what she meant.

It was one of those perfect days in early spring that felt more like summer except for a certain indefinable quality of light that proclaimed an earlier season. And the green of the grass and leaves still held all the freshness of a new year.

It was the kind of day to make one rejoice just to be alive.

And it was the kind of day on which one could wish for nothing better than to be driving out in the air with an attractive man beside one. For some reason she could not quite fathom, and despite the nuisance of her sore ankle, Gwen felt ten years younger this afternoon than she had felt in a long while.

She ought not to be feeling any such thing. But, on the other hand, why not? She was a widow and owed allegiance to no man. Lord Trentham was unmarried and, at present at least, unattached. Why should they not spend the afternoon in each other’s company? Whom were they likely to harm?

There was nothing wrong with a little romance.

If she had brought a parasol with her, she would have twirled it exuberantly above her head. Instead, she played a sprightly tune on an invisible keyboard across her thighs before clasping her hands more quietly in her lap.

The gig proceeded a short way along the driveway in the direction of the village, but then it looped back behind the house along a narrower lane, which then ran parallel to the cliffs, in the opposite direction from the village. There was a patchwork quilt of brown, yellow, and green fields and meadows on the one side, the cultivated park of Penderris on the other. The sea, several shades deeper blue than the sky, was visible beyond the park. The air was fragrant with the smells of new vegetation and turned soil and the salty tang of the sea.

And with the faint musky odor of Lord Trentham’s soap or cologne.

It was impossible to keep her shoulder and arm from brushing against his on the narrow seat of the gig, Gwen discovered. It was impossible not to be aware at every moment of his powerful thighs alongside hers, encased in tight pantaloons, and of his large hands plying the ribbons.

He was wearing a tall hat today. It hid most of his hair and shaded his eyes. He looked less fierce, less military. He looked more attractive than ever.

Her physical response to his presence was a little unnerving since she had never really experienced it with any other man. Not even with Vernon. She had thought him gorgeously handsome and wondrously charming when they had first met, and she had tumbled very quickly and willingly into love with him. She had liked his kisses before they married, and she had often enjoyed the marriage bed after.

But she had never felt like this with Vernon or anyone else.

Breathless.

Filled with an exuberant energy.

Aware of every small detail with her senses. Aware that he was aware, though neither of them spoke during the journey. At first, she could not think of anything to talk about. Then she realized that she did not really need to talk at all and that the silence between them did not matter. It was not uncomfortable.

After a mile or two the lane sloped downward, and almost at the bottom of a long hill they turned onto an even narrower track in the direction of the sea. Soon even the track disappeared, and the gig bounced over coarse grass to the edge of the low cliff.

Lord Trentham got out to unhitch the horse and tether it to a sturdy bush nearby. He allowed it enough room to graze while they were gone.

He draped a blanket over his arm and handed her some cushions, as he had done when he took her into the garden two days ago, and he lifted her out and carried her down to the cove below along a narrow zigzagging path, across a gentle slope of pebbles, and onto flat golden sand. Long outcroppings of rock stretched out to the sea on either side of the small beach. It was indeed a private little haven.

“The coastline constantly surprises, does it not?” she said, breaking the long silence at last. “There are long, breathtakingly lovely stretches of beach. And sometimes there are little pieces of paradise, like this. And they are equally beautiful.”

He did not answer. Had she expected him to?

He carried her in the direction of a large rock planted firmly in the middle of the little beach. He took her around to the sea side of it and set her down on one foot, her back against the rock, while he spread the blanket over the sand. He took the cushions from her arms and tossed them down before helping her to sit on the blanket. He propped one cushion behind her back, plumped one beneath her right ankle, and folded the other beneath her knee. He frowned the whole while, as though his task required great concentration.

Was he regretting this? Had his invitation been impulsive?

“Thank you,” she said, smiling at him. “You make an excellent nursemaid.”

He looked briefly into her eyes before standing up and gazing out to sea.

There was not a breath of wind down here, she noticed. And the rock attracted the heat of the sun. It felt more than ever like a summer day. She undid the fastenings of her cloak and pushed it back over her shoulders. She was wearing just a muslin dress beneath it, but the air felt pleasantly warm against her bare arms.

Lord Trentham hesitated for a few moments and then sat down beside her, his back against the rock, one leg stretched out in front of him, the other bent at the knee, his booted foot flat on the blanket, one arm draped over his knee. His shoulder was a careful few inches away from her own, but she could feel his body heat anyway.

“You play well,” he said abruptly.

For a moment she did not understand what he was talking about.

“The pianoforte?” She turned her head to look at him. His hat had tipped forward slightly on his head. It almost hid his eyes and made him look inexplicably gorgeous. “Thank you. I am competent, I believe, but I have no real talent. And I am not angling for further compliments. I have heard talented pianists and know I could practice ten hours a day for ten years and not come close to matching them.”

“I suppose,” he said, “you are competent in everything you do. Ladies generally are, are they not?”

“The implication being that we are competent in much but truly accomplished in little and talented in even less?” She laughed. “You are undoubtedly right in nine cases out of ten, Lord Trentham. But better that than be utterly helpless and useless in everything except perhaps in looking decorative.”

“Hmm,” he said.

She waited for him to be the next to speak.

“What do you do for fun?” he asked.

“For fun?” That was a strange word to use to a grown woman. “I do all the usual things. I visit family members and play with their children. I attend dinners and teas and garden parties and social evenings. I dance. I walk and ride. I—”

“You ride?” he asked. “After the accident you had?”

“Oh,” she said, “I did not for a long while after. But I had always enjoyed riding, and not doing so cut me off from much interaction with my peers and much personal pleasure. Besides, I hate not doing something simply because I do not have the courage. Eventually I forced myself back into the saddle, and more recently I have even forced myself to encourage my mount to a pace faster than a crawl. One of these days I shall actually allow it to gallop. Fear must be challenged, I have found. It is a powerful beast if it is allowed the mastery.”

He was gazing with half-closed eyes at the incoming water. The sun was glinting off its surface.

“What do you do for fun?” she asked.

He thought about it for a while.

“I feed lambs and calves when their mothers cannot,” he said. “I work in the fields of my farm and particularly in the vegetable garden behind the house. I watch and somehow participate in all the miracles of life, both animal and vegetable. Have you ever smoothed bare soil over seeds and doubted you would ever see them again? And then a few days later you see thin, frail shoots pushing above the soil and wonder if they will ever have the strength and endurance to survive. And before you know it, you have a sturdy carrot or a potato the size of my fist or a cabbage that needs two hands to hold.”

She laughed again.

“And that is fun?” she asked.

He turned his head and their eyes met. His looked very dark beneath the brim of his hat.

“Yes,” he said. “Nurturing life instead of taking it is fun. It makes a man feel good here.” He patted a lightly closed fist against the left breast of his coat.

He was titled. He was very wealthy. Yet he worked on his own farms and toiled in his own vegetable garden. Because he enjoyed doing so. Also because it offered him some absolution for having spent his years as an officer killing men and allowing his own men to be killed.

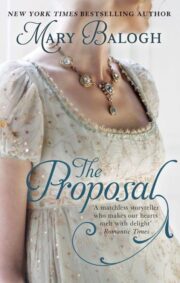

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.