And he retreated behind the large oak desk that stood near the window.

Gwen wondered about his stammer. It was the only imperfection she could detect in his person. Perhaps he too had come through war physically unscathed but had gone out of his head, as Lord Trentham had phrased it. She had not thought a great deal before this week about the mental strain of being a military man. And yet it showed a lamentable lack of imagination on her part that she had not.

She read for a while, and then Lady Barclay found her and invited her to the conservatory to see the plants. There were some long wicker seats there, she explained, on which Lady Muir could rest her foot. They sat there and talked for a whole hour. Later, they went for tea in the drawing room.

It was Lady Barclay who dined with her that evening.

She wanted to broach the subject of Lady Barclay’s loss and assure her that she understood, that she too had lost a husband under violent, horrifying circumstances, that she too felt guilty over his death and doubted she would ever free herself of the feeling. And perhaps it was more than just a feeling. Perhaps she really was guilty.

But she said nothing. There was nothing in Lady Barclay’s manner to suggest that she would welcome such intimacy. Anyway, Gwen never talked about the events surrounding Vernon’s death or the fall that had caused it. She suspected she never would.

She never even thought about those events. Yet in some ways she never thought of anything else.

Later in the evening, she admitted when asked that she played the pianoforte, though not with any particular flair or talent. It did not matter. She was persuaded to cross the drawing room on her crutches in order to sit at the instrument and play, rusty fingers and all. Fortunately, she acquitted herself tolerably well. And then she was persuaded to remain there in order to accompany Lord Darleigh as he played his violin. She moved to the harp with him afterward while he explained to her how he was learning to identify all the many strings without seeing them.

“And his next trick, Lady Muir,” the Earl of Berwick said, “is to play the strings once he has identified them.”

“Heaven defend us,” Lord Ponsonby added. “Vincent was far less d-dangerous when he had his sight and the only weapons at his disposal were a sword and a giant cannon. He is threatening to start embroidering, Lady Muir. Lord knows where his needle will end up. And we have all heard horror stories about silken bonds.”

Gwen laughed with them all, including Lord Darleigh himself.

When she withdrew to her room soon after, she was not allowed to climb the stairs with her crutches. A footman was summoned to carry her up.

Lord Trentham did not offer.

She had not seen him all day. She had scarcely heard his voice all evening.

She hated the idea that she had very possibly ruined his stay at Penderris. She could only hope that Neville would not delay in sending the carriage once he had received her letter.

She felt depressed after she had been left alone in her room. She was not tired. It was still quite early. She was also rather restless. The crutches had given her a taste of freedom but not the real thing. She wished she could look forward to a long early morning walk or, better yet, a brisk ride.

She did not feel like reading.

Oh dear, Lord Trentham was so dreadfully attractive. She had been aware of him with every nerve ending in her body all evening. If she was being strictly honest with herself, she would be forced to admit that she had chosen her favorite apricot evening gown with him in mind. She had played the pianoforte aware only of him in the small audience. She had looked everywhere in the room except at him. Her conversation had seemed too bright, too trivial because she had known he was listening. Her laughter had seemed too loud and too forced. It was so unlike her to be self-conscious when in company.

She had hated every moment of an evening that on the surface had been very pleasant indeed. She had behaved like a very young girl dealing with her first infatuation—her first very foolish infatuation.

She could not possibly be infatuated with Lord Trentham. A few kisses and a physical attraction did not equate love or even being in love. Good heavens, she was supposed to be a mature woman.

She had rarely spent a more uncomfortable evening in her life.

And even now, alone in her own room, she was not immune—at least to the physical attraction.

What would it be like, she found herself wondering, to go to bed with him?

She shook off the thought and reached for the book she had taken from the library. Perhaps she would feel more like reading once she started.

If only Neville’s carriage could appear, like some miracle, tomorrow. Early.

She felt suddenly almost ill with homesickness.

Chapter 8

The last two days had been sunny and springlike in all but temperature. Today that deficiency had more than corrected itself. The sky was a clear blue, the sun shone, the air was warm, and—that rarest of all weather phenomena at the coast—there was almost no wind.

It felt more like summer than spring.

Hugo stood alone outside the front doors, undecided what he would do for the afternoon. George, Ralph, and Flavian had gone riding. He had decided not to accompany them. Although he could ride, of course, it was not something he did for pleasure. Imogen and Vincent had gone for a stroll in the park. For no specific reason, Hugo had declined the invitation to join them. Ben was in the old schoolroom upstairs, a space George had set aside for him for the punishing exercises to which he subjected his body several times a week.

Ben had assured George that he would look in upon Lady Muir when he was finished and make sure she was not left alone for too long after the departure of her friend.

Hugo had agreed to see Mrs. Parkinson on her way in George’s carriage, and that was what he had just done. She had looked archly up at him and simpered and commented that any lady fortunate to have him beside her in a carriage would never feel nervous—not about the hazards of the road at least, she had added. Hugo had not taken the hint to play the gallant and accompany her to the village. He had drawn her attention instead to the burly coachman up on the box and assured her that he had never heard of any highwaymen being active in this part of the country.

What he really ought to do, he thought now, since he had almost deliberately isolated himself for the afternoon, was go down onto the beach, his favorite old haunt. The tide was on the way in. He loved to be close to the water, and he liked being alone.

He had not looked at Lady Muir just now when he had stepped into the morning room to escort her friend to the carriage. He had merely inclined his head vaguely in her direction.

It was really quite disconcerting how much two reasonably chaste kisses could discompose a man. And probably a woman too. She had not spoken to him before he escorted her friend from the room, and though he had not looked at her, he was almost certain that she had not looked at him either.

Ach, this was ridiculous. They were behaving like two gauche schoolchildren.

He turned and stalked back into the house. He tapped on the morning room door, opened it, and stepped inside without waiting for an invitation. She was standing at the window, propped on her crutches, gazing out. At least, he assumed she had been gazing out. She was now looking at him over her shoulder, her eyebrows raised.

“Vera has gone?” she asked him.

“She has.” He took a few steps closer to her. “How is your ankle?”

“The swelling has gone down considerably today,” she said, “and it is far less painful than it was. Even so, I cannot set the foot to the ground and would probably be unwise even to try. Dr. Jones was very specific in his instructions. I am annoyed with myself for allowing the accident to happen, and I am annoyed with myself for being so impatient to heal. I am annoyed with myself for being in a cross mood.”

She smiled suddenly.

“It is a lovely day,” he said.

“As I see.” She looked back out through the window. “I have been standing here trying to decide whether I will take my book and sit in the flower garden for a while. I can walk that far unassisted.”

“When the tide is coming in,” he said, “it cuts one part of the long beach off from the rest and makes a secluded, picturesque cove out of it. I have been there often when I simply want to sit and think or dream, or sometimes when I want to swim. It is a couple of miles along the coast but is still a part of George’s land. It is quite private. I thought I might go over there this afternoon.”

Actually he had not given a thought to the cove until he started to speak to her.

“It can be approached by gig,” he added, “and the cliff is not high there. The sands are quite easy to reach. Would you care to come with me?”

She maneuvered the crutches and turned to face him. She was just a little thing, he thought. He doubted the top of her head reached his shoulder. She was going to say no, he thought, half in relief. What the devil had prompted him to make such an offer anyway?

“Oh, I would,” she said softly.

“In half an hour?” he suggested. “You will need to go upstairs to get ready, I daresay.”

“I can go up alone,” she said. “I have my crutches.”

But he strode forward, relieved her of them, and swung her up into his arms before striding off in the direction of the stairs. He waited for a tirade that did not come. Though she did sigh.

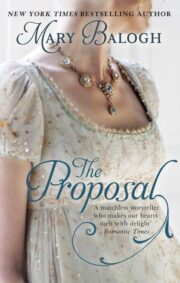

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.