He raised his eyebrows.

“You are sorry?”

“It must be a coveted treat to return here each year,” she said. “But you have been uncomfortable this evening, and I can only conclude that I am the cause. I have written to my brother and asked him to send the carriage as soon as possible, but it will be a few days before it arrives to take me home. In the meanwhile, I shall try to stay out of your way. Any serious involvement between us is out of the question for all sorts of reasons—it is out of the question for both of us. And I have never been one for meaningless flirtation or dalliance. My guess is that you have not either.”

“You came up early tonight because of me?” he asked her.

“You are a member of a group,” she said. “I came up because of the group. And I really am a little tired. Sitting around all day makes me sleepy.”

Any serious involvement between us is out of the question for all sorts of reasons.

Only one reason came to mind. She was of the aristocracy; he was of a lower class despite his title. It was the only reason. She was being dishonest with herself. But it was a huge reason. On both their parts, as she had said. He needed a wife who would pull cabbages from the kitchen garden with him, and help feed those lambs that could not suck from their mothers, and shoo chickens and their squawking and flapping wings out of the way in order to retrieve their eggs. He needed someone who knew the social world of the middle classes so that a husband could be found for Constance.

He bowed stiffly. Words were clearly superfluous.

“Good night, ma’am,” he said and left the room without waiting for her reply.

He thought he heard a sigh as he closed the door.

It was mostly Vincent’s turn that night.

He had woken up in a fit of panic in the morning and had been fighting it all day. Such episodes were growing less frequent, he reported, but when they did happen, they were every bit as intense as they had ever been.

When Vincent first came to Penderris, he had still been more than half deaf as well as totally blind—a result of a cannon exploding close enough to have propelled him all the way back to England in a million pieces. By some miracle he had escaped both dismemberment and death. He had still been something of a wild thing, whom only George had been able to calm. George had often taken the boy right into his arms and held him close, sometimes for hours at a time, crooning to him like a baby until he slept. Vincent had been seventeen at the time.

The deafness had cleared, but the blindness had not and never would. Vincent had given up hope fairly early and had adjusted his life to the new condition with remarkable determination and resilience. But hope, pushed deep inside rather than banished completely, surfaced occasionally when his defenses were low, usually while he slept. And he would awake expecting to see, be terrified when he discovered he could not, and then be catapulted down to the depths of a dark hell when he realized that he never would.

“It robs me of breath,” he said, “and I think I am going to die from lack of air. Part of my mind tells me to stop fighting, to accept death as a merciful gift. But the instinct to survive is more powerful than any other and I breathe again.”

“And what a good thing that is,” George said. “Despite all that might be said to the contrary, this life is worth living to the final breath with which nature endows us.”

The rather heavy silence that succeeded his words testified to the fact that it was not always an easy philosophy to adopt.

“I can picture some things and some people quite clearly in my head,” Vincent said. “But I cannot with others. This morning it struck me—for only about the five thousandth time—that I have never seen any of your faces, that I never will. Yet every time I have such a thought, it is as raw as it was the first time I thought it.”

“In the case of Hugo’s ugly countenance,” Flavian said, “that is a signal mercy, Vincent. We have to look at it every day. And in the case of my face … Well, if you were to see it, you would despair, for you will never look so handsome yourself.”

Vincent laughed, and all of them smiled.

Hugo noticed Flavian blinking away tears.

Imogen patted Vincent’s hand.

“Tell me, Hugo,” Vincent said, “were you kissing Lady Muir when I came to fetch you in for tea? I could hear no conversation as I approached the flower garden though Ralph had assured me you were both out there. He probably sent me deliberately so that the lady would not be embarrassed at what I might see.”

“If you think I am going to answer that question,” Hugo said, “you must have cuckoos in your head.”

“Which is all the answer I need,” Vincent said, waggling his eyebrows.

“And my lips are sealed,” Ralph said. “I will neither confirm nor deny what I saw through the morning room window, though I will say that I was shaken to the core.”

“Imogen,” George said, “will you cater to our collective male laziness and pour the tea?”

The Duke of Stanbrook produced a pair of crutches for Gwen the following morning, explaining that they had been needed when his house was a hospital but had lain untouched and forgotten for several years since. He had had them tested for safety, he assured her. He measured them for length and had a few inches sawn off them. He had them sanded and polished. Then Gwen was able to move around to a limited degree.

“You must promise me, though, Lady Muir,” he said, “not to bring the wrath of Dr. Jones down upon my head. You must not dash about the house and up and down stairs for eighteen hours out of every twenty-four. You must continue to rest your foot and keep it elevated most of the time. But at least now you can move about a room and even from room to room without having to wait for someone to carry you.”

“Oh, thank you,” she said. “You cannot know how much this means to me.”

She took a turn about the morning room, getting used to the crutches, before reclining on the chaise longue again.

She felt a great deal less confined for the rest of the day, though she did not move about a great deal. Vera spent most of the morning with her, as she had the day before, and stayed until after luncheon.

Her friends, she reported happily, quite hated her for being on intimate visiting terms with the Duke of Stanbrook. His crested carriage had been seen to stop outside her house a number of times. Their jealousy would surely cause them to cut her acquaintance if they did not find it more to their advantage to bask in her reflected glory and boast to their less privileged neighbors of being her friends. She also complained of the fact that His Grace did not see fit to send anyone in the carriage to bear her company and that again today she was not invited to take luncheon in the dining room with the duke and his guests.

“I daresay, Vera,” Gwen told her, “the duke is touched by your devotion and considers that you would find it offensive to be taken away from me when I cannot sit in the dining room with you.”

She wondered why she bothered to try to soothe ruffled feathers that never stayed smooth for long.

“Of course you are right,” Vera said grudgingly. “I would be offended if His Grace parted me from you for a mere meal when I have given up a large part of my day just to offer you the comfort of my company. But he might at least give me the opportunity to refuse his invitation. I am surprised that his chef serves only three courses for luncheon. At least, he serves only three here in the morning room. I daresay they enjoy a larger number of courses in the dining room.”

“But the food is plentiful and delicious,” Gwen said.

Vera’s visits were a severe trial to her.

After the Duke of Stanbrook had borne her friend off to his waiting carriage, Gwen felt a little agitated. What if Lord Trentham came again as he had yesterday? The weather was just as lovely. She could not bear to find herself tête-à-tête with him again. She had no business being attracted to him, or he to her. She had no business allowing him to kiss her, and he had no business asking it of her.

If he came again this afternoon, she thought, she could pretend to be asleep and to remain asleep. He would have no choice but to go away. But she was not sleepy today.

She was saved anyway from having to practice such subter-fuge. There was a tap on the door not long after Vera left, and it opened to reveal Viscount Ponsonby.

“I am on my way to the l-library,” he said in his languid voice and with his slight stammer. “Everyone else is off enjoying the sunshine, but I have such a stack of unanswered letters that I am in grave danger of being buried under it or lost behind it or some such dire thing. I must, alas, set pen to p-paper. It occurred to me that you may wish to try out your new crutches and come to select a book.”

“I would be more than delighted,” she said, and he stood in the doorway watching while she hoisted herself onto her crutches and moved toward him.

Her ankle was still swollen and sore to the touch. There was still no possibility of getting on a shoe or putting any weight on it. It was somewhat less painful today, however. And the cut on her knee was now no more than a scab.

Lord Ponsonby walked beside her to the library and turned a sofa that was by the fireplace so that light from the window would fall on it.

“You may remain here and read or w-watch me labor,” he said, “or you may return to the morning room after choosing a book. Or you may run up and down stairs, for that matter. I am not your jailer. If you need a volume from a high shelf, d-do let me know.”

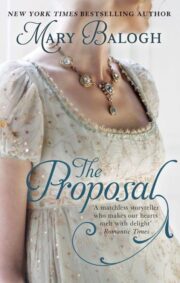

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.