“Most people,” he said, “snore when they sleep on their back.”

Trust him to say something totally unexpected.

Gwen raised her eyebrows. “And I do not?”

“Not on this occasion,” he said, “though you do sleep with your mouth partway open.”

“Oh.”

How dare he stand there watching her while she slept. There was something uncomfortably intimate about it.

“How is your ankle today?” he asked.

“I thought it would be better, but annoyingly it is not,” she said. “It is only a sprained ankle, after all. I feel embarrassed at all the fuss it is causing. You need not feel obliged to keep talking about it or asking me about it. Or to continue keeping me company.”

Or watching me while I sleep.

“You ought to have some fresh air,” he said. “Your face is pale. It is fashionable for ladies to look pale, I gather, though I doubt any wish to look pasty.”

Wonderful! He had just informed her that she looked pasty.

“It is a chilly day,” he said, “but the wind has gone down and the sun is shining, and you may enjoy sitting in the flower garden for a while. I’ll fetch your cloak if you wish to go.”

All she had to do was say no. He would surely go away and stay away.

“How would I get out there?” she asked instead and then could have bitten out her tongue since the answer was obvious.

“You could crawl on your hands and knees,” he said, “if you wished to be as stubborn as you were yesterday. Or you could send for a burly footman—I believe one of them carried you down this morning. Or I could carry you if you trust me not to become overfamiliar again.”

Gwen felt herself blushing.

“I hope,” she said, “you have not been blaming yourself for last evening, Lord Trentham. We were equally to blame for that kiss, if blame is the right word. Why should we not have kissed, after all, if we both wished to do so? Neither of us is married or betrothed to someone else.”

She had the feeling that her attempt at nonchalance was failing miserably.

“I may take it, then,” he said, “that you do not wish to crawl out on your hands and knees?”

“You may,” she said.

No more was said about the burly footman.

He turned and strode from the room without another word, presumably to go and fetch her cloak.

That had been nicely done of her, Gwen thought with considerable irony.

But the prospect of some fresh air was not to be resisted.

And the prospect of Lord Trentham’s company?

Chapter 6

It was chilly. But the sun was shining, and they were surrounded by primroses and crocuses and even a few daffodils. It had not occurred to Gwen before now to wonder why so many spring flowers were varying shades of yellow. Was it nature’s way of adding a little sunshine to the season that came after the dreariness of winter but before the brightness of summer?

“This is so very lovely,” she said, breathing in the fresh, slightly salty air. “Spring is my favorite season.”

She drew her red cloak more snugly about her as Lord Trentham set her down along a wooden seat beneath the window of the morning room. He took the two cushions she had carried out at his suggestion, placed one at her back to protect it from the wooden arm, and slid the other carefully beneath her right ankle. He spread the blanket he had brought with him over her legs.

“Why?” he asked as he straightened up.

“I prefer a daffodil to a rose,” she said. “And spring is full of newness and hope.”

He sat down on the pedestal of a stone urn close by and draped his arms over his spread knees. It was a relaxed, casual pose, but his eyes were intent on hers.

“What do you wish for your life that would be new?” he asked her. “What are your hopes for the future?”

“I see, Lord Trentham,” she said, “that I must choose my words with care when I am in your company. You take everything I say literally.”

“Why say something,” he asked her, “if your words mean nothing?”

It was a fair enough question.

“Oh, very well,” she said. “Let me think.”

Her first thought was that she was not sorry he had come to the morning room and suggested bringing her out here for some air. If she were perfectly honest with herself, she would have to admit that she had been disappointed when it was a footman who had appeared in her room this morning to carry her downstairs. And she had been disappointed that Lord Trentham had not sought her out all morning. And yet she had also hoped to avoid him for the rest of her stay here. He was right about words that meant nothing, even if the words were only in one’s head.

“I do not want anything new,” she said. “And my hope is that I can remain contented and at peace.”

He continued to look at her as though his eyes could pierce through hers to her very soul. And she realized that though she thought she spoke the truth, she was really not perfectly sure about it.

“Have you noticed,” she asked him, “how standing still can sometimes be no different from moving backward? For the whole world moves on and leaves one behind.”

Oh, dear. It was the house, he had said last evening, that inspired such confidences.

“You have been left behind?” he asked.

“I was the first of my generation in our family to marry,” she said. “I was the first, and indeed the only one, to be widowed. Now my brother is married, and Lauren, my cousin and dearest friend. All my other cousins are married too. They all have growing families and have moved, it seems, into another phase of their lives that is closed to me. It is not that they are not kind and welcoming. They are. They are all forever inviting me to stay, and their desire for my company is perfectly genuine. I know that. I still have remarkably close friendships with Lauren, with Lily—my sister-in-law—and with my cousins. And I live with my mother, whom I love very dearly. I am very well blessed.”

The assertion sounded hollow to her ears.

“A seven-year mourning period for a husband is an exceedingly long one,” he said, “especially when a woman is young. How old are you?”

Trust Lord Trentham to ask the unaskable.

“I am thirty-two,” she said. “It is possible to live a perfectly satisfying existence without remarrying.”

“Not if you want to have children without incurring scandal,” he said. “You would be wise not to delay too much longer if you do.”

She raised her eyebrows. Was there no end to his impertinence? And yet, what would undoubtedly be impertinence in any other man she knew was not in his case. Not really. He was just a blunt, direct man, who spoke his mind.

“I am not sure I can have children,” she said. “The physician who tended me when I miscarried said I could not.”

“Was he the man who set your broken leg?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“And you never sought a second opinion?”

She shook her head.

“It does not matter, anyway,” she said. “I have nieces and nephews. I am fond of them and they of me.”

It did matter, though, and only now at this moment did she realize how much it did. Such was the power of denial. What was it about this house? Or this man.

“It sounds to me,” he said, “as though that physician was a quack of the worst sort. He left you with a permanent limp and at the same time destroyed all your hope of bearing a child just after you had lost one—without ever suggesting that you consult a doctor with more knowledge and experience of such matters than he.”

“Some things,” she said, “are best not known for sure, Lord Trentham.”

He lowered his eyes from hers at last. He looked at the ground and with the toe of one large booted foot he smoothed out the gravel of the path.

What made him so attractive? Perhaps it was his size. For although he was unusually large, there was nothing clumsy about him. Every part of him was in perfect proportion to every other. Even his cropped hair, which should lessen any claim to good looks he might possess, suited the shape of his head and the harshness of his features. His hands could be gentle. So could his lips …

“What do you do?” she asked him. “When you are not here, that is. You are no longer an officer, are you?”

“I live in peace,” he said, looking back up at her. “Like you. And contentment. I bought a manor and estate last year after my father died, and I live there alone. I have sheep and cows and chickens, a small farm, a vegetable garden, a flower garden. I work at it all. I get my hands dirty. I get soil under my fingernails. My neighbors are puzzled, for I am Lord Trentham. My family is puzzled, for I am now the owner of a vast import/export business and enormously wealthy. I could live with great consequence in London. I grew up as the son of a wealthy man, though I was always expected to work hard in preparation for the day when I would take over from my father. I insisted instead that he purchase a commission for me in an infantry regiment and I worked hard at my chosen career. I distinguished myself. Then I left. And now I live in peace. And contentment.”

There was something indefinable about his tone. Defiant? Angry? Defensive? She wondered if he was happy. Happiness and contentment were not the same thing, were they?

“And marriage will complete your contentment?” she asked him.

He pursed his lips.

“I was not made for a life without sex,” he said.

She had asked for that one. She tried not to blush.

“I disappointed my father,” he said. “I followed him like a shadow when I was a boy. He adored me, and I worshipped him. He assumed, I assumed that I would follow in his footsteps into the business and take over from him when he wished to retire. Then there came that inevitable point in my life when I wanted to be myself. Yet all I could see ahead of me was becoming more and more like my father. I loved him, but I did not want to be him. I grew restless and unhappy. I also grew big and strong—a legacy from my mother’s side of the family. I needed to do something. Something physical. I daresay I might have sown some relatively harmless wild oats before returning to the fold if it had not been for … Well, I did not take that route. Instead, I broke my father’s heart by going away and staying away. He loved me and was proud of me to the end, but his heart was broken anyway. When he was dying, I told him that I would take over the reins of his business enterprises and that I would, if it was at all in my power, pass them on to my son. Then, after he died, I went home to my little cottage and bought Crosslands, which was nearby and just happened to be for sale, and proceeded to live as I had for the two years previous except on a somewhat grander scale. To myself I called it my year of mourning. But that year is up, and I cannot in all conscience procrastinate any longer. And I am not getting any younger. I am thirty-three.”

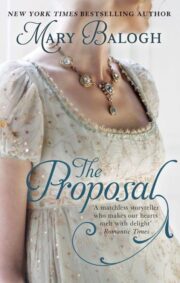

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.