“He is well,” Gwen said.

“It was Kilbourne’s wife, was it not,” the duke asked, “who turned out to be the long-lost daughter of the Duke of Portfrey?”

“Yes,” Gwen said. “Lily, my sister-in-law.”

“Portfrey and I were close friends in the long-ago days of our youth,” the Duke of Stanbrook said.

“He is married to my aunt,” she said. “Those family relationships are a little complicated, to say the least.”

The duke nodded.

“Lady Muir,” he said, “it will be best for you, I believe, if we excuse you from sitting at the dining room table with us. Although I could provide a stool for your foot, it would not be adequate. The good doctor was quite adamant in his instruction that you keep your foot elevated for the next week. You will, therefore, dine in here. I do hope that will not be too inconvenient for you. We will not desert you entirely, however. Hugo has been appointed to bear you company. I can assure you that he will not assail your ears with tales of his wealth or with suggestions that you marry him in order to secure a part of it for yourself.”

Her smile was austere.

“I daresay I will never live down that faux pas,” Lord Darleigh said ruefully.

The duke offered his arm to Lady Barclay and led her from the room. The others followed. Sir Benedict Harper, Gwen noticed, did not use his canes as crutches even though they looked sturdy enough to bear his weight. Rather, he walked slowly and with painstaking care, using them for balance.

The silence in the drawing room after the door had closed behind the diners seemed almost unbearably loud.

Chapter 4

It had not been his fault, Gwen thought, that joke and the coincidence of her being on the beach today of all days. It just felt as if it were his fault. She resented him anyway. She had just been horribly embarrassed.

And Lord Trentham looked as if he resented her. Probably because he had just been horribly embarrassed.

His eyes were on the door as though he could still see his fellow guests through its panels and longed to be on the other side with them. She wished quite fervently that he was there too.

“Will Sir Benedict ever walk without his canes?” she asked for something to say.

He pursed his lips, and for a moment she thought he would not answer.

“The whole world beyond these walls,” he said eventually, still watching the door, “would say a resounding no. The whole world called him fool for refusing to have the legs amputated and then for not accepting reality and resigning himself to living the rest of his life in bed or at least in a chair. There are six of us within this house who would wager a fortune apiece on him. He swears he will dance one day, and the only thing we wonder about is who his partner will be.”

Oh dear, she thought after another short silence, this was going to be an uphill battle.

“Do you often see people down on the beach?” she asked.

He turned to look at her.

“Never,” he said. “In all the times I have been down there, I have never encountered another soul who was not also from this house. Until today.”

There was a suggestion of reproach in his voice.

“Then I suppose,” she said, “it seemed a safe thing to say to your friends, who were teasing you. That you would find a woman to whom to propose marriage down on the beach, I mean.”

“Yes,” he agreed. “It did.”

She smiled at him, and then laughed softly. He looked back, no answering amusement in his face.

“It all really is funny,” she said. “Except that now you will doubtless be teased endlessly. And I am confined here for at least a week with a sprained ankle. And,” she added when he still did not smile, “you and I will probably be horribly embarrassed in each other’s company until I finally leave here.”

“If I could throttle young Darleigh,” he said, “without actually committing murder, I would.”

Gwen laughed again.

And silence descended once more.

“Lord Trentham,” she said, “you really do not need to bear me company here, you know. You came to Penderris to enjoy the companionship of the Duke of Stanbrook and your fellow guests. I daresay your suffering together here for so long established a special bond among you, and I have now intruded upon that intimacy. Everyone has been most kind and courteous to me, but I am quite determined to be as little of a nuisance while I must remain here as I possibly can be. Please feel free to join the others in the dining room.”

He still stood looking down at her, his hands clasped behind his back.

“You would have me thwart the will of my host, then?” he asked her. “I will not do it, ma’am. I will remain here.”

Lord Trentham. He could be anything from a baron on up to a marquess, Gwen thought, though she had never heard of him before today. And if what Viscount Ponsonby had said was correct, he was also extremely wealthy. Yet he did not have the manners of a thick plank.

She inclined her head to him and resolved not to utter another word before he did, though she would thereby be lowering her manners to the level of his. So be it.

But before the silence could become uncomfortable again, the door opened to admit two servants, who proceeded to move a table closer to the sofa and set it for one diner. Before those servants had time to leave the room, two others entered bearing laden trays. One was set across Gwen’s lap while the other was carried to the table, where the various dishes were set out for Lord Trentham’s dinner.

The servants left as silently as they had come. Gwen looked down at her soup and picked up her spoon as Lord Trentham took his place at the table.

“I beg your pardon,” Lord Trentham said, “for the embarrassment a seemingly harmless joke has caused you, Lady Muir. It is one thing to be teased by friends. It is another to be humiliated by strangers.”

She looked at him in surprise.

“I daresay,” she said, “I will survive the ordeal.”

He returned her look, saw that she was smiling, and nodded curtly before addressing himself to his dinner.

The Duke of Stanbrook had an excellent chef, Gwen thought, if the oxtail soup was anything to judge by.

“You are in search of a wife, Lord Trentham?” she said. “Do you have any particular lady in mind?”

“No,” he said. “But I want someone of my own sort. A practical, capable woman.”

She looked up at him. Someone of my own sort.

“I was not born a gentleman,” he explained. “My title was awarded to me during the wars, as a result of something I did. My father was probably one of the wealthiest men in England. He was a very successful businessman. But he was not a gentleman, and he had no desire to be one. He had no social ambitions for his children either. He despised the upper classes as idle wastrels, if the truth were told. He wanted us to fit in where we belonged. I have not always honored his wishes, but in that particular one I concur with him. It would suit me best to find a wife of my own class.”

Much had been explained, Gwen thought.

“What did you do?” she asked as she pushed back her empty soup bowl and drew forward her plate of roast beef and vegetables.

He looked back at her, his eyebrows raised.

“It must have been something extraordinary,” she said, “if the reward was a title.”

He shrugged.

“I led a Forlorn Hope,” he said.

“A Forlorn Hope?” Her knife and fork remained suspended above her plate. “And you survived it?”

“As you see,” he said.

She gazed at him in wonder and admiration. A Forlorn Hope was almost always suicidal and almost always a failure. He could not have failed if he had been so rewarded. And good heavens, he was not even a gentleman. There were not many officers who were not.

“I do not talk about it,” he said, cutting into his meat. “Ever.”

Gwen continued to stare for a few moments before resuming her meal. Were the memories so painful, then, that they were not even tempered by the reward? Was it there that he had been so horribly wounded that he had spent a long time here recovering his health?

But his title, she realized, sat uneasily upon his shoulders.

“How long have you been widowed?” he asked her in what, she guessed, was a determined effort to change the subject.

“Seven years,” she said.

“You have never wished to marry again?” he asked.

“Never,” she said—and thought of that strange, crashing loneliness she had felt down on the beach.

“You loved him, then?” he asked.

“Yes.” It was true. Despite everything, she had loved Vernon. “Yes, I loved him.”

“How did he die?” he asked.

A gentleman would not have asked such a question.

“He fell,” she told him, “over the balustrade of the gallery above the marble hall in our home. He landed on his head and died instantly.”

Too late it occurred to her that she might have answered with some truth, as he had done a short while ago—I do not talk about it. Ever.

He swallowed the food that was in his mouth. But she knew what he was about to ask even before he spoke again.

“How long was this,” he asked, “after you fell off your horse and lost your unborn child?”

Well, she was committed now.

“A year,” she said. “A little less.”

“You had a marriage unusually punctuated with violence,” he said.

Her answer had not needed comment. Or, rather, not such a comment. She set her knife and fork down across her half-empty plate with a little clatter.

“You are impertinent, Lord Trentham,” she said.

Oh, but this was her own fault. His very first question had been impertinent. She ought to have told him so then.

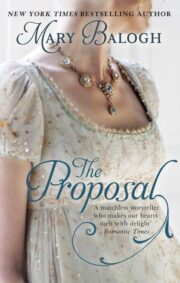

"The Proposal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Proposal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Proposal" друзьям в соцсетях.