“And I promise … I promise never to say good-bye to you …” And then, for no reason in particular, they laughed. Because it felt good to be young, to be romantic, even to be corny. The whole day had felt good. “Shall we go back now?” She nodded assent, and hand in hand they wandered back to where they had left the bikes. And two hours later, they were back at Nancy's tiny apartment on Spark Street, near the campus. Mike looked around as he let himself fall sleepily onto the couch and realized once again how much he enjoyed her apartment, how much like home it was to him. The only real home he had ever known. His mother's mammoth apartment had never really felt like home, but this place did. It had all Nancy's wonderful warm touches in it. The paintings she had done over the years, the warm earth colors she had chosen for the place, a soft brown velvet couch, and a fur rug she had bought from a friend. There were always flowers everywhere, and the plants she took such good care of. The spotless little white marble table where they ate, and the brass bed which creaked with pleasure when they made love.

“Do you know how much I love this place, Nancy?”

“Yeah, I know.” She looked around nostalgically. “Me, too. What are we going to do when we get married?”

“Take all these beautiful things of yours to New York and find a cozy little home for them there.” And then something caught his eye. “What's that? Something new?” He was looking at her easel, which held a painting still in its early stages but already with a haunting quality to it. It was a landscape of trees and fields, but as he walked toward it, he saw a small boy, hiding in a tree, dangling his legs. “Will he still show once you put the leaves on the tree?”

“Probably. But we'll know he's there in any case. Do you like it?” Her eyes shone as she watched his approval. He had always understood her work perfectly.

“I love it.”

“Then it'll be your wedding present—when it's finished.”

“You've got a deal. And speaking of wedding presents—” He looked at his watch. It was already five o'clock, and he wanted to be at the airport by six. “I should get going.”

“Do you really have to go tonight?”

“Yes. I'll important I'll come back in a few hours. I should be at Marion's place by seven thirty or eight, depending on the traffic in New York. I can catch the last shuttle back, at eleven, and be home by midnight Okay, little worrywart?”

“Okay.” But she was hesitant She was bothered by his going. She didn't want him to, and yet she didn't know why. “I hope it goes all right.”

“I know it will” But they both knew that Marion did only what she wanted to do, listened only to what she wanted to hear, and understood only what suited her. Somehow he knew they'd win her over though.

They had to. He had to have Nancy. No matter what. He took her in his arms one last time before slipping a tie around the collar of the sport shirt he was wearing and grabbing a lightweight jacket on the back of a chair. He had left it there that morning. He knew it would be hot in New York, but he knew, too, that he had to appear at Marion's apartment in coat and tie. That was essential. Marion had no tolerance for “hippies,” or for nobodies … like Nancy. They both knew what he was facing when they kissed good-bye at the door.

“Good luck.”

“I love you.”

For a long time Nancy sat in the silent apartment looking at the photograph of them at the fair. Rhett and Scarlet, immortal lovers, in their silly wooden costumes, poking their faces through the holes. But they didn't look silly. They looked happy. She wondered if Marion would understand that, if she knew the difference between happy and silly, between real and imaginary. She wondered if Marion would understand at all.

Chapter 2

The dining room table shone like the surface of a lake. Its sparkling perfection was disturbed only on the edge of the shore, where a single place setting of creamy Irish linen lay, adorned by delicate blue and gold china. There was a silver coffee service next to the plate, and an ornate little silver bell. Marion Hillyard sat back in her chair with a small sigh as she exhaled the smoke from the cigarette she had just lit. She was tired today. Sundays always tired her. Sometimes she thought she did more work at home than she did at the office. She always spent Sundays answering her personal correspondence, looking over the books kept by the cook and the housekeeper, making lists of what she had noticed needed to be repaired around the apartment and of items needed to complete her wardrobe, and planning the menus for the week. It was tedious work, but she had done it for years, even before she'd begun to run the business. And once she'd taken over for her husband, she still spent her Sundays attending to the household and taking care of Michael on the nurse's day off. The memory made her smile, and for a moment she closed her eyes. Those Sundays had been precious, a few hours with him without anyone interfering, anyone taking him away. Her Sundays weren't like that anymore; they hadn't been in too many years. A tiny bright tear crept into her lashes as she sat very still in her chair, seeing him as he had been eighteen years before, a little boy of six, and all hers. How she loved that child. She would have done anything for him. And she had. She had maintained an empire for him, carried the legacy from one generation to the next. It was her most valuable gift for Michael. Cotter-Hillyard. And she had come to love the business almost as much as she loved her son.

“You're looking beautiful, Mother.” Her eyes flew open in surprise as she saw him standing there in the arched doorway of the richly paneled dining room. The sight of him now almost made her cry. She wanted to hug him as she had all those years ago, and instead she smiled slowly at her son.

“I didn't hear you come in.” There was no invitation to approach, no sign of what she'd been feeling. No one ever knew, with Marion, what went on inside.

“I used my key. May I come in?”

“Of course. Would you like some dessert?”

Michael walked slowly into the room, a small nervous smile playing over his mouth, and then like a small boy he peered at her plate. “Hm … what was it? Looks like it must have been chocolate, huh?”

She chuckled and shook her head. He would never grow up. In some ways anyway. “Profiteroles. Care for some? Mattie is still out there in the pantry.”

“Probably eating what's left.” They both laughed at what they knew was most likely true, but Marion reached for the bell.

Mattie appeared in an instant, black-uniformed and lace-trimmed, pale-faced and large-beamed. She had spent a lifetime running and fetching and doing for others, with only a brief Sunday here and there to call her own, and nothing to do with it once she had the much coveted “day.” “Yes, madam?”

“Some coffee for Mr. Hillyard, Mattie. And … darling, dessert?” He shook his head. “Just coffee then.”

“Yes, ma'am.”

For a moment Michael wondered, as he often had, why his mother never said thank you to the servants. As though they had been born to do her bidding. But he knew that was what his mother thought. She had always lived surrounded by servants and secretaries and every possible kind of help. She had had a lonely upbringing but a comfortable one. Her mother had died when she was three, in an accident with Marion's only brother, the heir to the Cotter architectural throne. The accident had left only Marion to become a substitute son. She had done so very effectively.

“And how is school?”

“Almost over, thank God. Two more weeks.”

“I know. I'm very proud of you, you know. A doctorate is a wonderful thing to have, particularly in architecture.” For some reason the words made him want to say, “Oh, Mother!” as he had when he was nine. “We'll be contacting young Avery this week, about his job. You haven't said anything to him, have you?” She looked more curious than stern; she didn't really care. She had thought it a little childish that Michael thought it so important to surprise Ben.

“No, I haven't. He'll be very pleased.”

“As well he should be. It's an excellent job.”

“He deserves it.”

“I hope so.” She never gave an inch. “And you? Ready for work? Your office will be finished next week.” Her eyes shone at the thought. It was a beautiful office, wood-paneled the way his father's had been, with etchings that had belonged to her own father, an impressive leather couch and chairs, and a roomful of Georgian furniture. She had bought it all in London over the holidays. “It really looks splendid, darling.”

“Good.” He smiled at his mother for a moment “I have some things I want to get framed, but I'll wait till I take a look at the decor.”

“You won't even need to do that. I have everything you'll need for the walls.”

So did he. Nancy's drawings. There was sudden fire in his eyes now, and an air of watchfulness in hers. She had seen something in his face.

“Mother—” He sat down next to her with a small sigh and stretched his legs as Mattie arrived with the coffee. “Thank you, Mattie.”

“You're welcome, Mr. Hillyard.” She smiled at him as warmly as she always did. He was always so pleasant to her, as though he hated to bother her, not like … “Will there be anything else, madam?”

“No. As a matter of fact … Michael, do you want to take that into the library?”

“All right.” Maybe it would be easier to talk in there. His mother's dining room had always reminded him of ballrooms he had seen in ancestral homes. It was not conducive to intimate conversation, and certainly not to gentle persuasion. He stood up and followed his mother out of the room, down three thickly carpeted steps, and into the library immediately to their left. There was a splendid view of Fifth Avenue and a comfortable chunk of Central Park, but there was also a warm fireplace and two walls lined with books. The fourth wall was dominated by a portrait of Michael's father, but it was one he liked, one in which his father looked warm—like someone you'd want to know. As a small boy he had come to look at that portrait at times, and to “talk” aloud to his father. His mother had found him that way once, and told him it was an absurd thing to do. But later he had seen her crying in that room, and staring at the portrait as he had.

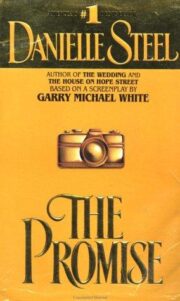

"The Promise" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Promise". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Promise" друзьям в соцсетях.