Soon, Rogov came out into the corridor too. Alov darted up to him and showed him his OGPU identity card.

“What were you just talking about with Babloyan?” he demanded.

The two of them stood glaring stiffly at one another.

“My bosses are insisting that I arrange an interview with Stalin,” said Rogov at last. “So, I asked Comrade Babloyan to help. But he told me there’s nothing he can do.”

“Is that all you talked about?” asked Alov, his voice thick with mistrust.

“Well, no. We talked about actresses too.”

“Which actresses?”

“The ones who just performed; the girls from the Blue Blouse. Dunya Odesskaya has made quite an impression on Comrade Babloyan, it seems.”

Alov pulled his amber beads from under his cuff and began to click them rapidly to and fro. He was smarting with fury. Just think, this sleek, pampered bourgeois prig thought he had the right to discuss any woman he chose and to demand an interview with Stalin himself!

“Excuse me,” said Rogov, “but I have to go.”

The upstart did not even feel the slightest alarm at being faced by an OGPU agent. It seemed he had no idea that Alov could have him deported and his visa annulled with no more than a snap of his fingers.

With great effort, Alov forced himself to speak politely and calmly. “We’re interested in talking to a woman by the name of Nina Kupina,” he said. “You don’t happen to know where she is?”

Rogov shrugged. “No idea. We met on a driving course.”

“Don’t lie to me!” Alov said. “A few months ago, you were interested in the whereabouts of this same individual.”

It was clear from Rogov’s face that he had not expected the OGPU to be so well-informed.

“So, what do you say?” Alov asked in an insinuating tone.

Rogov winced like some businessman pestered by a street beggar. “Is this an interrogation?”

“No, it’s an offer,” said Alov. “I’d like you to cooperate with us. Who knows when you might need a connection in the OGPU?”

“Good evening.” Rogov left without even holding out his hand.

Just you watch out! thought Alov. I’ve got my eye on you.

If there was one thing Alov could not bear, it was when other people failed to treat him with respect.

31. THE SOLOVKI PRISON CAMP

As soon as the passport made out in the name of Hilda Schultz was ready, Klim went to buy Nina’s ticket to Berlin. Fortunately, there were no queues for international trains.

On the way to Saltykovka, he pictured how Nina would meet him at the gate and ply him with impatient questions. “Well?” she would ask him. “How did it go with the ticket?” Then he would pull a sad face just to tease her before producing his prize.

Whenever Nina heard good news, she reacted with girlish delight, gasping excitedly and dancing in celebration, and Klim could not wait to make her happy.

But this time, it was not Nina who opened the gate to Klim but Countess Belov. Her face wore an anxious expression, her eyebrows set in a tragic arch.

Klim felt his blood run cold. “What is it?”

“Elkin’s here,” the countess answered in a dreadful whisper.

Klim followed her into the small kitchen, which was hung with garlands of dried mushrooms, and stopped still, staring at the man sitting by the window.

The man was so thin that his bony shoulders protruded from his dirty military-style tunic. His crew-cut hair had gone completely gray, and his face was deeply lined. He still resembled the Elkin of old, yet at the same time, he looked quite different. It was unbelievable that a man could age so much in two months.

“What happened to you?” asked Klim, stunned.

Elkin smiled. All the teeth on the left-hand side of his mouth were missing.

“I was sent to the Solovki prison camp,” he said, “but I managed to run away.”

Nina came in to the kitchen carrying two pails of water on a carrying pole and put them down on the floor.

“Now, we’ll heat up some water,” said Countess Belov, turning to Elkin, “and you shall have a proper wash.”

Nina nodded briefly in Klim’s direction and began helping their hostess to light the stove. Not a word of greeting. It was as if she was afraid of insulting their guest by showing Klim any particular attention.

“Why did they arrest you?” Klim asked Elkin.

“The Feodosia authorities got an order to find and detain any Nepmen, bourgeois, and other undesirable elements. They knew me personally—I fixed their cars for them, so they didn’t have to go very far to find me.”

“Did they formally accuse you of anything?”

“They don’t give a damn about formal accusations!” Nina snapped out. “The Bolsheviks need free labor. They don’t understand anything about efficient production, and their outgoing costs are so high that they don’t have enough money to pay the workforce. So, they need slaves to cut down timber in Solovki and work in the mines for nothing.”

Putting an iron pot of water inside the big masonry oven, Nina slammed its shutter. Her movements were abrupt and violent. It seemed she was on the point of grabbing something and smashing it to smithereens.

“How on earth did you escape?” Klim asked Elkin. “I’ve heard it’s impossible—Solovki is on some island in the White Sea.”

“I didn’t get that far,” said Elkin gloomily. “I ran away from a transit camp on the mainland.”

Klim felt a chill run down his spine. Everybody in the USSR had heard rumors of the camps in the north, but there was no reliable information about them.

“Perhaps you’d let me interview you?” he asked. “I’m sure United Press would be interested in your story.”

Elkin looked Klim up and down, scornfully. “So, you’re already thinking how to make a fast buck, are you?”

“I’d just like to know—”

“Mr. Rogov, I have nothing left but my story, and I intend to sell it to the highest bidder. I need to get out of this blessed country of ours, and it costs three hundred rubles to organize an illegal passage across the border to Poland.”

“We’ll give you the money!” Nina exclaimed, her voice full of emotion.

Neither she nor the countess seemed in the slightest bit concerned that Elkin had accused Klim of seeking to profit from another’s misfortune.

Countess Belov glanced at the clock on the wall. “We should put the potatoes on to boil,” she said. “The children will be back from school soon.”

Nina ran out to the yard to the cold cellar, and Klim set off after her.

She opened the hatch and was about to go down the cellar steps when he reached her.

“You never even asked me about the passport,” he said. “I’ve brought you everything.”

She turned and stared at him blankly. “Yes, thank you.”

There was no celebratory dance. Klim stood next to the open mouth of the cellar, breathing in the damp smell of earth and decay.

“It’s fine,” he said. “You don’t have to thank me.”

Nina came out again with a pipkin of small, sprouting potatoes.

“I know Elkin’s your friend,” said Klim. “I just want you to know that once you’ve chartered that boat for the German refugees, we won’t have any money left to live on. I don’t speak German, and it’ll be some time before I can find work. My friend Seibert is a famous journalist in Germany, and he’s barely scraping a living publishing articles here and there…. I hope you don’t mind me speaking honestly?”

“Of course not,” Nina nodded. Her face was wan and miserable. A curl had escaped her comb and hung down beside her cheek.

“I’ll do whatever I can to fix things for us,” said Klim. “But all of a sudden, you come up with some plan of your own like getting Elkin across the border to Poland—”

Nina looked down at the ground.

“I want to help him because it’s so easy to imagine myself in his place. The Bolsheviks are just like the Mongol army back in the middle ages. They ambush peaceful civilians and make them into slaves. If you’re set to work logging or building one of their mines or plants—then that’s it. You’ll end up a cripple, physically and morally…. I was just imagining what would happen to me if they got their hands on me. And it could happen at any minute! What would I do? I would have to rely on the kindness of others—and that’s all Elkin has to rely on.”

Nina took a deep, shuddering breath and put her arm around Klim. “You may not understand what I’m doing, but it won’t come between us, I promise you. Just trust me!”

Klim clasped Nina to him. The problem was he could not just trust her. The paradise they were building was too fragile. One false movement, one strong gust of wind, and the whole thing would collapse. What awaited them then? No waterfalls and sunsets; only jealousy and suspicion.

“It will be better for everyone,” said Nina, “if I give Elkin the money to get him over the border. He can take our dollars out of the country, and I’ll meet him in Berlin. And then we can pay for the ship.”

Klim sighed. “You do as you see fit.” He took the “Book of the Dead” from his pocket and handed it to her. “Here. This is my diary. Read it and then burn it. I can’t take it with me to Germany in any case. All printed material and manuscripts have to pass the censor if I want to take them across the border.”

“So, you’d let me into your innermost secrets?”

“I think we need to learn how to understand each other. Even if it means sharing some painful things.”

“Would you like me to tell you about Oscar too?” asked Nina.

Klim shook his head. “I’m prepared to postpone that particular pleasure until 1976. When you’re eighty years old, I’ll stop worrying that you’re about to leave me, and I’ll be ready to hear your confessions.”

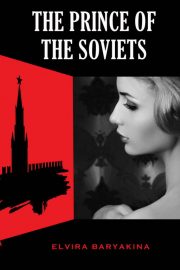

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.