Gloria slapped down some clay with her hand and stared at Nina. “Sit down!” she ordered, rising heavily to her feet from the rickety bench. “I want to have a look at you.”

“What for?” Nina asked.

“That’s my business. You just shut your eyes and model something with the clay. Whatever you like.”

Nina shrugged and sat down at the potter’s wheel. Closing her eyes, she took a piece of clay in her fingers and began to shape it.

“Stop!” Gloria said.

She looked at what Nina had made as if it was something extraordinary.

“A man trap!” Gloria muttered. “That’s your past…. It’s got a tight grip on you. I can feel it.”

Nina looked down at the clay in front of her: a flat circle with uneven, jagged edges. Actually, she thought it looked more like a beer-bottle top.

Gloria took out another piece of clay from the barrel. “Shut your eyes and have another go.”

It was clear that Gloria was trying to work out what was on Nina’s mind. This time, Nina attempted to make the shape of a heart, but she ended up with a strange shape pitted with holes left by her fingers.

“That’s a piece of cheese!” exclaimed Gloria. “‘At the top of the tree sat Mr. Crow, clutching a piece of cheese in his beak…’ Have you heard this fable? You hold onto your prize tight, or a fox might come running past and take it away.”

Nina was puzzled. “Are you talking about Galina?” she asked, warily.

Frowning, Gloria squashed the “man-trap” and the “cheese” together in her fist to make a single lump.

“Get up!” she ordered, and sitting back down in Nina’s place, she set the wheel turning again with the pedal.

“Daft girl!” she muttered. “Do you have a brain at all behind those curls?”

Nina stood, wiping her fingers with a cloth, waiting for some sort of explanation, but Gloria did not say a word. The wheel turned with a soft hiss, and a new pot began to take shape under the old woman’s gnarled fingers.

“I don’t know what to do,” said Nina timidly. “I don’t know if he still loves me or if he still wants—”

The cockatoo bent its head toward Gloria’s ear and began to jabber something.

“Mm-hm,” nodded the old woman, raising her at Nina.

“You should think about making him feel good with you rather than bad without you. And now, off with you. I have work to do.”

All the way to Feodosia, Nina thought about what Gloria had told her.

When was the last time she and Klim had felt good together? It had been several years ago. Their love had become like opium—it gave a short illusion of happiness but was actually destroying them both. Klim had been the first to realize this and decided to put an end to the torment.

Kitty took her spillikins out of Nina’s bag. Elkin had made her a whole set of tiny models, each no larger than a child’s fingernail. There was a pail with a handle, a samovar, a saw, and a carpenter’s plane, a hundred different items in all. The idea of the game was to tip them into a pile and then take them out one by one with a little hook, making sure not to touch anything else.

Kitty had no luck with the spillikins—the bus bounced too much as it drove over the potholes.

Klim and I have no luck sorting our relationship out either, thought Nina gloomily. But nobody is to blame. It just happened that we have had a rough ride.

The train had arrived early for a change.

Taking Kitty in her arms, Nina ran through the dim station building and onto the sun-drenched platform. Cheerful passengers hurried past them, carrying suitcases, baskets, and butterfly nets.

Nina saw a crowd gathered at the last car and ran toward the back of the train.

“Stop pushing!” the conductor shouted as he handed out parcels and letters. “You’ll all get your turn.”

He sorted deftly through the packages and envelopes with his wrinkled hands. “Not, this one’s not yours, nor this one either.”

At last, he handed over a plywood box to Nina.

Kitty jumped up and down beside her impatiently. “Mommy! Open it quickly!”

Having settle down on the bench under a poplar tree, Nina cut open the package with a knife borrowed from a vendor selling watermelons nearby.

“What’s inside?” fussed Kitty “Are there any toys?”

There were biscuits, sugar, and chocolate wrapped in paper. At the very bottom, under Norwegian canned goods, there was a letter. Klim wrote that the Krasin icebreaker had saved all the crew members of Nobile’s expedition and that the foreign journalists had not been allowed anywhere. He promised that he would soon be coming to Feodosia to bring Elkin his money and to collect Kitty from Nina. It seemed that it was a lot easier to buy long-distance train tickets up in Archangelsk.

“Thank you for helping me out in a tight spot,” wrote Klim at the end of the letter. “I hope Kitty didn’t make too much of a nuisance of herself.”

Nina felt as if the wind had been taken out of her sails. She had been eagerly awaiting Klim’s arrival, but now, she was dreading it. He was planning to take Kitty away and leave her alone.

Elkin saw that Nina was suffering and tried to raise her spirits.

“You and I must definitely go on a tour of the ancient world,” he told her. “I’ll show you such beautiful sights they’ll take your breath away.”

Nina agreed to go. She had to take her mind off her gloomy thoughts in some way.

They spent a day wandering through the rocky spurs of the Kara Dag and staring into the mouths of chasms.

“You and I are standing on an extinct volcano,” Elkin told Nina. “Can you imagine what it would have been like here in prehistoric times? Boiling lava, and the earth shuddering with earthquakes…. But now, everything is quiet and peaceful.”

They climbed a steep cliff and looked down on a breathtaking view.

“It’s so beautiful!” Nina said, almost in tears with emotion. “When you can’t tell where the sea joins the sky, it feels as if you’re on a huge ship floating through the air.”

Elkin took a deep breath. “Nina, I’ve been wanting to say something to you for a while now, and I think now is a good time—”

Nina looked at him in alarm. Had he made up his mind to propose to her? Please, anything but that!

“I have something to say to you too,” she said quickly.

For some time, Nina had been aware that there was only one way to save Elkin from a humiliating refusal: to tell him beforehand all about her relations with Klim.

She told him everything: how she had met her ex-husband, how they had traveled about Russia during the civil war, and how they had emigrated to China.

Elkin listened for a long time, his face frozen into an expressionless smile. Clearly, he understood that Nina was trying to save his dignity, and he was grateful to her for it.

They sat on the edge of the cliff, watching the clouds over the bay turning pink in the sunset.

“I think both of us appeared on this earth at the wrong place at the wrong time,” said Elkin in a thick voice. “I should have been born a hundred years later, and you would have done well in the late eighteenth century. You could have been the ruler of some small, enlightened duchy.”

“What would I have done there?” Nina asked him.

“Well, you would have had secret lovers, a beautiful, well-kept capital city, and loyal subjects. Artists would have painted you as a bright angel surrounded by cupids, and poets would have written ingenious madrigals about you. What else could you wish for?”

“And the story would have ended either with a foreign invasion or a palace coup,” said Nina, getting to her feet. “It’s the same thing in the twentieth century—I was faced with the choice of being sent into exile or put in jail. And there was nothing the greatest intellects could do to help me. It’s just my fate, I suppose.”

They came home after dark. Gloria came out to meet them with the kerosene lamp, her face like thunder.

“Where have you been all this time?” she shouted, taking Nina by the arm and dragging her into the house.

“What happened?” Nina asked in alarm.

Gloria opened the door to Nina’s room and showed her Kitty, lying doubled up on the bed in agony. “See for yourself!”

Nina rushed to her daughter. “What’s the matter with you?”

Kitty’s face had swollen up until her eyes were no more than tiny slits, and a painful rash had broken out all over her cheeks.

“It hurts all over again,” she sobbed, flinging her head back.

Nina looked at the child in bewilderment. She had been sure that when Kitty was with her, her daughter would not be taken sick.

“Mommy’s here…. Mommy will make it better,” Nina said, holding Kitty close to her chest. “We’ll go to Feodosia and find you a doctor.”

“What’s the good of getting the girl to a doctor when her fool of a mother feeds her the devil only knows what?” retorted Gloria, pointing to an empty chocolate wrapper on the floor.

“Her father sent it,” Nina said. “Kitty loves sweet things…”

Gloria stamped her foot angrily. “If you had any sense, you’d have realized what the problem was long ago!”

Then she swept out, leaving the paraffin lamp on the chest.

Nina sat for a long time on Kitty’s bed, shaken to the core. So, this was the cause of Kitty’s illness: Klim had been giving her chocolate. Nina had heard that some people had a serious reaction to it.

Soon, however, Nina’s train of thought went off on a different tack. Now that she knew the secret of Kitty’s illness, she could use it to get Klim away from Galina. Nina could tell him that the child became ill when she was with his new lover, and he would believe it.

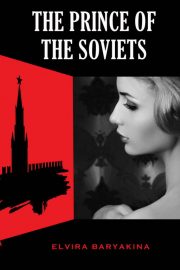

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.