As soon as I opened the door, Weinstein launched into me with a string of accusations.

“I really thought we understood one another, and this is how you repay me. If this happens one more time, there’ll be hell to pay!”

I felt relieved to hear this. It seems that as it’s the first such misdemeanor, I’m being forgiven and allowed to stay in Moscow. All the same, I felt like a schoolboy called in to the headmaster’s office. What damn business is it of that devil Weinstein what I choose to publish abroad?

Still, there was no point in arguing with him.

I think I can forget about getting an interview with Stalin.

I have to face facts: Nina has disappeared without a trace, and I can’t go on living on memories.

Kitty needs a mother, and I need a wife. But I can’t imagine any other woman playing that part in my life.

For all her excellent qualities, Galina is too much of a cud-chewing herbivore for my liking. A cow may be a helpful animal, but I can’t get excited about it.

Nina, on the other hand, was like a graceful twilight predator with glowing eyes. She would never agree to be anyone’s servant. It wasn’t always easy living with her, but I could never look at her without admiration. Who could take her place?

I can see quite clearly what Galina’s up to. She’s counting on the fact that I’ll get used to all these home comforts. I suppose she thinks one day I’ll just give in and I won’t bother looking elsewhere for a wife. She wants to domesticate me, to put me in a nice warm stable with a straw for bedding and a bunch of hay. Sit and munch and forget about everything!

I would hate myself if I took up with a woman out of mere gratitude.

What the hell? I was actually starting to plan my life without Nina.

The enemy article cost me dearly. Now the censors smile sweetly at me and cut half of everything I write. I have to work almost twice as hard as I used to.

In order to have at least something to write about, I have subscribed to the press cuttings office service. Every day now, a courier brings me a big pile of clippings. Once I’ve looked through some article which has passed the censor, I can insist that it’s an official bulletin and needs to be sent abroad.

But my catch is getting smaller every day. Ever since the routing of the opposition, it’s clear that it is not a good idea to argue about the direction the country should be taking. These days, countless congresses and meetings are held in Moscow, at which the speakers talk for hours without actually saying anything at all. To protect themselves against any accusations of freethinking, they cite the pronouncements of Lenin and Marx and stick to tried-and-true phrases such as “the fight against the recalcitrant core of the petty bourgeoisie” or “steering a course toward a union with the peasantry.” Who can tell what they actually mean? Nobody. Wonderful!

Just to keep afloat, I am forced to shuffle words, people, and events on a regular basis. As for the moral implications of what I am doing, I have stopped even thinking about them. This is the only way I can hope to get a telegram through to the Press Office.

Mass repressions have begun, the main victims being profiteers who are accused by the government of pushing up prices. I come into the censors’ office with a bulletin that reads, “Eighteen Men Shot,” hoping that they’ll at least allow something insipid, such as “Ruthless Purges,” to be sent abroad.

“What’s the point in that?” Weinstein is bound to object. “Who cares about profiteers? We can’t send that out.”

“It’s an official announcement by Izvestia,” I remind him. “Or do you think that Izvestia is giving a distorted picture of the Party line?”

Weinstein acts as if he has not heard what I just said. “We’ve opened up a factory canteen,” he says, shoving a clipping across this desk toward me. “You say you’re a friend of the Soviet Union. Why don’t you write about how we’re helping the working man?”

I also act as if I’m hard of hearing and put my briefcase on his clipping. For a while, we talk about the weather and what’s on in the Moscow theaters. Then I come back to the subject of the profiteers.

“I know you want to write about the factory canteen,” I say, “but I’m afraid my editors aren’t interested in that sort of story.”

“So, what do they want?” asks Weinstein in aggrieved tones.

I sigh heavily. “They just want blood and violence.”

The censor eventually passes the title “Decisive Purges,” puts his stamp on my report, and I run to the telegraph office.

This is how it works these days: “Flour Distribution at Standstill” is changed to “Delays in Dispatch of Bumper Grain Supplies”; “Meat Shortages” to “The Victory of Vegetarianism,” and so on.

Seibert told me that when he found out about how rebellious Cossacks had been exiled to Siberia, he managed to get the news over the border by writing, “State Guarantees Resettlement for Cossack Families.”

11. CHRISTMAS NIGHT

Kitty went several times to visit Tata. At first, Klim was pleased she had found herself a friend, but soon, his daughter began to use expressions like “a class-based attitude” and “rotten idealism.” One day, instead of asking for Klim to read her a fairytale at bedtime, Kitty asked for the “Young Pioneer’s Solemn Oath.”

The following day, Tata rang Klim to demand that Kitty be given a topical, revolutionary name.

“I’ve made up a list of names,” she said, “so you can choose: either Barricade, Progressina, Diamata, or Ninel. ‘Diamata’ comes from ‘dialectical materialism,’ and ‘Ninel’ is ‘Lenin’ backward.”

Klim told Tata that his daughter was quite revolutionary enough.

“Actually,” he said, “‘Kitty’ stands for ‘Kill the Imperialist Traitors of Tomorrow’s Youth.’”

“You don’t say!” Tata gasped in admiration. “Kitty never told me that! I promise you, I’ll make such a fine communist out of your daughter you won’t believe it!”

Afrikan went out into the forest and bought back a moss-covered fir tree, which he put up in the living room. Galina and Kapitolina spent all Christmas Eve making paper lanterns while Kitty cut pictures at random from postcards and punched holes in them to make decorations.

The window panes were half coated in snow, but inside, the room was wonderfully warm and inviting, smelling of fir sap and the smoke of birch logs.

Klim picked up from the table a sealed envelope, which Galina had given him earlier, and opened it. It was Tata’s Christmas present: an article from The Pioneer’s Pravda.

The Christmas tree is a survival of the benighted past, which encourages children to destroy the forest. Besides which, pine forest is one of the mainstays of national industry in the USSR.

If by some chance you are unaware of this and have already bought a fir tree, be sure to decorate it with red stars and ribbons and, when you dance around the tree, sing Pioneer songs.

Santa Claus is a reactionary element; his place should be taken by a Red Army Commander or a OGPU worker who can tell the children about his heroic fight to free the Soviet people.

At the end of the article Tata had added a handwritten note:

Uncle Klim pleese read my letter to Kitty!

Tell yore dad that a Crissmas tree is just a stupid survival of the old rejeem. He shud know this or he is not with us the workers and only pretending to be. I am not coming to your Crissmas party. Come to mine and we will play storming the tsar’s palase.

When Galina went out in the kitchen to check on the pastry for the pie, Klim followed her.

She lifted the pan lid, breathed in, and closed her eyes in pleasure.

“What a delicious smell!” she said. “When I was little, our cook would make a wonderful apple pie every year, and I would stuff myself so that I could barely move afterward.”

She gazed at Klim, her eyes shining. “It’s wonderful that you can cook on a proper range,” she added. “At home, we have to use kerosene stoves. Coal is too expensive, and we never have enough of it.”

“Your daughter seems to have taken it upon herself to educate Kitty and me,” said Klim and held out Tata’s letter to Galina.

She scanned the note and then threw it angrily into the range. “The little pest! She’s incorrigible. No matter how much I thrash her—”

“What? Do you beat her?”

“I don’t beat her badly. I just give her a taste of the belt from time to time. To keep her in line.”

Klim felt his hands tightening into fists despite himself. He had been thrashed as a child, and the memory of it was a source of a profound sense of humiliation.

“Never beat people smaller and weaker than you are,” said Klim, enunciating each word coldly and deliberately. “Don’t you see how despicable it is?”

Galina realized that she should have held her tongue, but she still tried to defend herself. “It’s the only language Tata understands!”

“No, it’s that you have no idea how else to deal with her. Children simply stop listening to you if you punish them all the time. Tata can’t live in a state of constant fear, believing that her mother thinks she’s bad. She has only one way of protecting herself: to ignore all the insulting things you say.”

For too long, Klim had concealed a growing annoyance with Galina.

“Adults who beat children,” he said, “are like lackeys taking pleasure in the fact that for once, they can exert power over somebody else. They grovel to their bosses and then take it all out on some defenseless victim who can’t get away from them.”

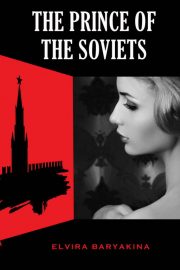

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.