A jazz band, the only one in the whole of the city, plays popular western tunes—all this is to make a good impression on foreigners. But once they have a drink inside them, all the foreign guests want to hear something more exotic: revolutionary songs and gypsy romances.

Often at these banquets, I am approached by beautiful ladies who come up and sit beside me. The interesting thing is that these women are all different—some are blondes, some brunettes, some slim, some voluptuous. The same thing happens to all the foreign correspondents. The OGPU is clearly trying to work out what our tastes are.

Seibert laughs at me. “Stop being so difficult,” he tells me. “The OGPU are at their wit’s end. If you keep being so stubborn, they’ll send you a handsome young boy one of these days.”

He’s quite happy to get acquainted with every last one of these women.

The cult of love has entirely vanished from the USSR. All the knights in shining armor have been killed or driven out of the country, and traditional patriarchal customs reign supreme. For those at the top, a woman is a symbol of success, rather like a medal or a ceremonial weapon, and among the workers, she is regarded as a “unit of labor”—and so has to be healthy, sturdy, and politically educated.

Sometimes, coming back from yet another of these Soviet society events, I feel so weary and sick at heart that I wonder what on earth I am doing here.

Galina always meets me at the door and gives me a full account of everything she has done for the household that day. Then she proudly shows me some decorated bottle or picture frame she has bought at auction and says, “Isn’t it beautiful?”

We stand there in the middle of the room. I wait for Galina to go, and she waits for me to ask her to stay.

Naturally, I am the first to lose patience: I tell her I need to do some work. Galina nods, sighs, and leaves, closing the door quietly behind her.

In my native land, it is now quite forbidden to write the truth. If I am caught in the criminal act of doing so, everybody will be held to account—Galina, Weinstein, the women at the telegraph office, and all the other kind people who help me every day.

The worst of it is that even if I did write the truth, it would not interest anybody outside Russia. Statistics indicate that Americans are showing less and less interest in foreign news. If, a few years ago, nine percent of newspaper columns were devoted to reports from abroad, now it is only two and a half percent. And that’s for all foreign countries, including Britain, Germany, Japan, and China—countries of far more interest to America than the USSR.

It’s a vicious circle. Readers have no interest in Russia because they know nothing about it, and meanwhile, I can’t tell them anything meaningful. What can foreign readers hope to find out from my censored reports? That far, far away in a snow-covered realm called the Soviet Union live strange people who like to torment themselves and others? “Well, why should we care as long as they stay away from us?” they might answer.

My reports lack a human face—they don’t reflect what life is like in the USSR. And it’s not only censorship that’s to blame. A telegram to London costs fifteen cents a word, and everything I put in my bulletin has to fit the budget. It’s useless to ask for more expenses: the only thing United Press is prepared to pay for without hesitation is an interview with Stalin.

When I asked to organize a meeting with Stalin, Weinstein looked at me as if I had lost my mind.

“Why on earth would Comrade Stalin be interested in speaking to you?”

“It would be good to hear about his views and his future plans,” I said.

Weinstein began to lose his temper. “Can you imagine some correspondent from a Russian news agency going to Washington and, as soon as he gets there, asking for a meeting with President Coolidge?” he asked.

I told him that President Coolidge had press conferences with journalists twice a week, but it was no use.

“I expect the American president hasn’t got much to do, and that’s why he can chat to every Tom, Dick, and Harry who comes along,” he said. “But Comrade Stalin has got enough on his hands without having to think about you.”

I told Owen about our conversation, and he asked me to think of how I might be able to lure Stalin to an interview.

Unfortunately, there’s nothing we can offer that might interest Stalin. The man isn’t looking for fame: he keeps to himself, only appearing in public twice a year at the Revolution anniversaries and Worker’s Day parades. He’s rather like some phantom living in an ancient castle. All his portraits are carefully retouched. The only people who see him close up are the Kremlin domestic staff and a dozen or so close confidants.

I decided in any case that twice a month, I’ll send an official request for an interview. I figure if I keep knocking at the same door for long enough, maybe somebody will open it up—at least to have a look at the tiresome pest outside and find out what he wants.

Seibert tells me he’s been doing exactly the same for three years. The two of us now have a bet to see which of us will be the first to get an interview.

I’ve had a daring idea. If I do manage to get a meeting with Stalin, I’ll ask for his help in finding Nina. One word from him will be enough to set all the Moscow bureaucrats in action.

Sometimes, I think it’s my only hope.

8. A PROBLEM CHILD

As far as Galina knew, Klim had neither a wife nor a lover. He had no interest in prostitutes, but he clearly had an eye for female beauty; Galina would be driven to impotent fits of jealous rage when she saw him staring at some attractive girls from the Communist Youth organization. He never looked at her like that.

Galina was amazed at the change that had taken place in her. Until recently, she had heartily condemned foreign capitalists and their evil ways and been certain that the triumph of communism was all she needed to be happy. But no sooner had she gone to work for Klim than all her former convictions had vanished like smoke. She could not help herself: she realized now that she liked elegant manners, sophisticated tastes, intelligent conversation, and even something as vulgar as money.

Klim did not think himself rich and kept talking about how he could not afford this or that. He had no idea what real poverty was, of how it wore you down, day after day, year after year, to scrimp and save all the time—even when it came to buying bread.

Now, Klim was dreaming of buying an automobile so that he could race Seibert to the main telegraph office with his dispatches. Meanwhile, Galina could not save enough money to buy mittens for her daughter.

“Ask the master for a bit extra,” Kapitolina had advised her. “He’s kind. He won’t refuse.”

But Galina did not want to ask Klim for anything. She needed more than a crumb thrown her way in charity now and again. What she needed was a husband to drag her out of the morass she had fallen into years ago.

She and Klim were now on friendly terms, and Galina began to work toward a private plan. She would help Klim make a brilliant career for himself in Moscow, making herself indispensable so that when his contract with United Press expired, he would marry her and take her and Tata in with him.

“It’s essential that Weinstein singles you out as a ‘friendly journalist,’” she advised Klim. “Then the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs won’t be afraid to help you. In Moscow, everything comes down to connections. If they see you as one of them, you’ll become a real expert on Soviet affairs because you’ll get to talk to all the right people.”

“Even Stalin?” Klim asked.

“Even Stalin.”

Galina surmised that the quickest route to Klim’s heart was through Kitty. He loved his daughter and felt guilty that he was unable to give her a “normal” childhood.

Kitty was desperate to go and play outside with the other children, but Klim would not let her because the neighborhood kids would tease her, calling her “slit-eyed.” However proudly Soviet papers wrote of the “inseparable friendship of nations,” it was a different story in Moscow’s yards and children’s playgrounds. There was too much that was different about Kitty: her race, her clothes, and the foreign expressions she used when she spoke. All this aroused both curiosity and dislike among strangers, and invariably, some child or adult would start to pick on her when she went outside.

The casual racism they encountered every day drove Klim into a rage.

“Idiots,” he would fume. “They don’t understand that difference is a wonderful thing! Kitty knows games they’ve never even heard of. She can tell stories and show them things. She can let them play with her toys, but all they want to do is shove her into a snowdrift and laugh in her face.”

Galina would nod in agreement. When the occasion presented itself, she told Klim that her own daughter, who was twelve, would be happy to play with children of any nationality. She was determined to introduce Kitty to Tata and do everything she could to encourage a friendship between them.

As a matter of fact, Galina was ashamed of her daughter. Tata was ugly and not very bright. Almost all the girls in her class at school were homely—they had grown up in the years of civil war and suffered from poor nutrition and constant bouts of illness. But even compared to them, Tata was puny—she was a whole head shorter than other girls her age, and with her straggly ginger braids, her snub nose, and her ear-to-ear grin, she looked like an underfed gnome.

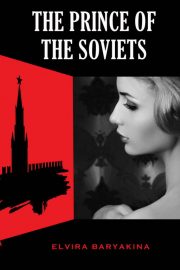

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.