‘Your Majesty, who understands my loss as few others can, will grant me this. Your Majesty, you will leave me guardian of my children. It is the only thing which can console me now.’

The King nodded.

‘So it shall be,’ he said.

Augusta sighed with relief and was aware of triumph. Fred was dead, no longer there to overshadow her. Now was the time for the true Augusta to emerge.

Augusta sent for her eldest son. She was seated at her table and there were papers before her; when she saw George she rose and held out her arms.

He ran into them and she embraced him crying: ‘My poor fatherless boy.’

George wept with her and as he did so thought of his father lying dead in his coffin and the pain he must have suffered before his death. He wept bitterly for the loss of that kind man and the fact that his passing had made him Prince of Wales. There was a difference in being Prince of Wales and the son of the Prince of Wales. He had sensed it immediately. He was expecting a summons hourly to appear before his terrifying grandfather.

Augusta dried her tears. She had lost dear Fred, but there were compensations. There was power and there was Lord Bute.

‘Your dear kind Papa left a paper which he would have given to you on your eighteenth birthday had he lived. But now that he has… gone… he would wish you to have it at once, for, my son, you will have to grow up quickly. You will have to learn to be a King. You understand full well what your father’s death means to you… what changes it has brought in your position.’

‘Yes, Mamma,’ said George mournfully.

‘Then we will read this paper together, shall we? We will see what instructions dear kind Papa has left you.’

‘Yes, Mamma.’

She opened the papers and spread them on the table, and together they read:

‘Instructions for my son George drawn up by myself for his good, that of my family and for that of his people, according to the ideas of my grandfather and best friend, George I.’

Augusta looked at her son significantly. ‘You see, he did not trust his father, our present King, your grandfather. Ah, his grandfather was always a good friend to him. How different it would have been if he had been his father…’

‘It was a pity they had to quarrel,’ George said.

‘Anyone would quarrel with the King,’ replied Augusta fiercely. ‘We shall have to be very careful to avoid trouble now we no longer have your dear Papa to care for us.’

George read what his father had written:

‘As always I have had the tenderest paternal affection for you, and I cannot give you stronger proof of it than in leaving this paper in your mother’s hands, who will read it to you from time to time and will give it to you when you come of age or when you get the crown. I know you will always have the greatest respect for your mother… .’

‘I hope it too,’ said Augusta. He took her hand and kissed it.

‘You know it, Mamma.’

‘Bless you, my son.’ She glanced down at the paper with him. ‘Your father was always a man of peace,’ she said. ‘It was only when the need arose that he would take to arms. He was very different from his younger brother, the Butcher Cumberland.’

‘If you can be without war let not your ambition draw you into it. A good deal of the National Debt must be paid off before England enters into a war. At the same time never give up your honour nor that of the nation. A wise and brave Prince may oftentimes without armies put a stop to the confusion, which ambitious neighbours endeavour to create.’

Reading these instructions George began to have a deep sense of responsibility. Before he had always believed that there was plenty of time for him to learn. He had never before seriously thought of being King of England. It was something for the very distant future. His father had been a comparatively young man with at least twenty years to live, and twenty years in the opinion of a thirteen-year-old boy was a lifetime. And now here he was with an ageing grandfather, given to choleric rages, who could die at any moment – the only barrier between young George and the throne. It was an alarming prospect.

He must learn all he could as quickly as possible. He must study these papers. He read feverishly; he must balance the country’s finances; he must understand business; he must seek true friends who would not flatter him but tell him the truth. He must separate the thrones of Hanover and England and never attempt to sacrifice the latter for the former as both his grandfather and his great-grandfather had done. Uppermost in his mind must be the desire to convince Englishmen that he was an Englishman himself, born in England, bred in England, and an Englishman not only through these matters but by inclination. Never let the people of England believe for a moment that he saw himself as a German whose loyalties were first for Germany.

Frederick finished his injunctions by recommending his mother to his care and also the rest of the family, his brothers and sisters.

‘I shall have no regret never to have worn the crown if you do but fill it worthily,’ he ended.

George lifted eyes swimming with tears to his mother’s face.

‘But, Mamma, it is almost as though he knew he were going to die.’

‘Sometimes these revelations come to us,’ she answered. ‘You see how he loved you, how he loved us all. You will want to do all that he wished, I know.’

‘Yes, Mamma,’ answered George fervently.

‘He would have wanted me to guide you, my son, for he had more faith in me than in anyone.’

‘I know it, Mamma. I feel so young, so…so unworthy.’

‘Trust in me, my son. Rely on me and all will be well.’

‘It is what I want to do above all else.’

She kissed him warmly; he was hers to mould; and he was the future King.

It was characteristic of the King that his resentment towards his son should not end with the latter’s death. In the presence of the window and children he allowed his sentimentality to get the better of him; but he was not going to change his attitude now.

Frederick was a young puppy who ought to have remained in Hanover. He would have liked to see William, Duke of Cumberland, King of England, and if it had been possible to make him so, he would have done it. It was what dear dead Caroline would have wished. Perhaps it was not too late now. That boy George was a simpleton. Prince of Wales indeed! When there was William, a fine figure of a man, the hero of the’45, and people could say what they liked, it was William who had saved the throne and driven that Stuart puppy yelping back to his French masters. William was the man who should take the throne, not a young puppy scarcely out of his nursery, son of that impudent rascal who ought never to have been brought to England.

Of one thing the King was certain – there should be no fine funeral honours for Fred. No grand ceremonies was the order. Let no one forget that although he was the King’s son and Prince of Wales he was no friend of the King’s. A simple funeral, then, with none of the nobility – who considered themselves the friends of the King – to attend. There would have to be some lords to carry the pall and attend the Princess, he supposed, but let it rest there. He wanted everyone to know that he considered the death of his eldest son no major calamity.

So the funeral of Frederick was less of an occasion than it was expected to be; and as when the cortège came out of the House of Lords it was raining, there were not many who cared to stand about in such weather to see it pass on its way to the Abbey.

Bubb Dodington was indignant. Bubb was like a man demented. The Prince should have had better medical attention, he declared; the Prince should have had great funeral honours. Poor Bubb! He was worried as to what the future held for him. He had been the Prince’s ardent supporter and friend, so it was hardly likely that the King would look with favour on him. And what else was there? A young boy Prince of Wales, thirteen years old, and a Princess Dowager who had never opened her mouth except to agree with her husband.

His only hope was to attach himself as speedily as possible to the Princess Dowager, to seek to advise her, and if possible to keep the rival Court alive which could form a nucleus about the new heir and guide him in the way he was to go.

It was a sad state of affairs.

The indifference of the people showed clearly that they did not share Bubb’s views. Frederick Prince of Wales was dead. Just another of those Germans, said the people. The whole lot of them were not much use, and it was a pity they had ever come here. If Bonnie Prince Charlie had not been a Catholic…But he was, and at least the Germans were Protestants, and they were comic enough to provide a little amusement now and then.

The people were laughing at Frederick’s epitaph which delighted them so much that it was spoken and sung in every place where men and women congregated; in fact, it made Frederick more popular in death than he had been in life.

Here lies Fred

Who was alive and is dead.

Had it been his father,

I had much rather;

Had it been his brother,

Still better than another;

Had it been his sister,

No one would have missed her;

Had it been the whole generation,

Still better for the nation.

But since it’s only Fred

Who was alive and is dead,

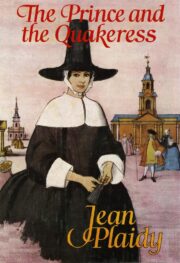

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.