Cumberland turned away from Lord Bute as though he had not spoken and said he would like to have the chance of teaching the boys something about the strategem of war.

Frederick replied that the boys had the best tutors in the country and he and the Princess were very pleased with their progress.

Cumberland nodded ironically and replied that he was sure of that – that the Prince and Princess of Wales were pleased, he meant.

Then Frederick suggested that as the time set for his sons’ lessons was not yet at an end, he and the Princess should show the Duke the gardens at Cliveden, as he was sure he would find something there to interest him.

Trouble in the family. It was distressing. George wished that they could all be friends together and that his grandfather did not hate his father, and that when an uncle called it could be an occasion for rejoicing rather than for anger, for he was well aware of the indignation this impromptu visit had aroused.

His mother talked of his uncle. He was a crude man, a brutal man. He liked bloodshed. When she spoke Uncle Cumberland’s name she did so with loathing. He loved war, this uncle. It was not so much that he wished to save the crown as that he wanted to kill… for the sake of killing. He liked the sight of blood; he liked to see men suffer. The people called him The Butcher.

The Butcher? George shivered at the name.

The Butcher, repeated his mother. That was when they heard of all his cruelty at Culloden. Oh, when he had returned from that battlefield they had shouted for him in the streets. They had reverenced Duke Billy, as they called him; but when they heard what had really happened, the cruelty he had delighted in practising they called him ‘Butcher’.

‘It is a hateful name to be given to a man,’ said George.

‘Hateful indeed,’ replied his mother. ‘Why, when it was proposed that he should be elected an Alderman of the City… this was after Culloden, one of the aldermen said: “Let it be of the Butchers.” So you see that is how the people think of him. Once when there was a disturbance at the Haymarket Theatre he lost his sword and the people started to sing: “Billy the Butcher has lost his knife.” That is what the people think of your Uncle Cumberland. How different he is from your father. Did he tell you that your father wanted to take command of the forces that went against the Pretender? Of course, your grandfather wouldn’t hear of that. He wanted all the glory for the Butcher. How different it would have been if your father had obtained the command. There would have been victory just the same – but glorious, not shameful victory. Did your uncle tell you that your father obtained the release of Flora MacDonald, that your father is a kind, human man, who is tolerant in his ideas?’

‘He did not,’ said George. ‘He did not mention that lady. Who is she?’

‘She is a brave woman. She is mistaken, of course, because she supported the Stuarts. But then, she is Scottish and knew no better.’

‘Uncle Bute is Scottish.’

A soft look spread itself across the Princess’s face. ‘You should not mention his name in the same breath as that woman’s. His loyalty to us is all the more to be admired because he is Scottish.’

‘Oh yes, yes, Mamma.’

She was a little embarrassed under his gaze. She said quickly: ‘I was telling you of Flora MacDonald. She helped Charles Edward Stuart to escape and was captured and brought to the Tower. It was your father who pleaded for leniency for this woman; he pointed out that she was a simple creature who was led astray. He obtained her freedom. He is a good tolerant man.’

‘I’m so glad Papa did that.’

‘You should be glad you have such a good kind Papa. And I can tell you this, your Uncle Cumberland is no friend to him. His great desire is to take the throne from him. He hates your dear kind Papa simply because he was born before he was and so is Prince of Wales. What do you think of any man who can hate your dear kind Papa? Must he not be a rogue to do so?’

George agreed. Only a rogue could hate dear kind Papa.

Augusta was brought to bed of another boy – her fifth.

He was christened Frederick William and it was decided, to George’s consternation, that he was to be one of the sponsors. It was his first public duty and he was terrified that he would make a fool of himself. It was easy to confide his fears to Lord Bute who did not laugh at him but told him that there was nothing to fear, and actually explained the whole ceremony to him. It was very simple, said Lord Bute, and if there was anything George feared at any time he would be honoured and delighted if he would come and tell him about it.

‘I will,’ declared George.

His father would have been kind, but Lord Bute always seemed to sense his uncertainties and be ready with his comfort before it was asked. And his mother was so pleased when Lord Bute offered his advice. ‘It is as though you had two kind fathers,’ she would say. ‘You are a fortunate Prince.’

Fortunate indeed, thought George, when he remembered the stories of how his grandparents had left his father in Hanover when they came to London and how he had had to threaten to elope with his cousin before they would bring him to London. What disaster if that had happened! He would not then have married Mamma. And what would have happened to him and Edward, and William and Henry, and Augusta and Elizabeth, to say nothing of this newest arrival to whom he was to act as sponsor.

Grandfather had given his permission which it was necessary to receive, but fortunately he was away in Hanover, where he so often was.

‘Long may he stay there,’ said Papa, and Mamma echoed his words as she always did.

So fortunately the old King would not be present at the ceremony; and with kind Papa to help him – and, of course, dear Uncle Bute – it might not be such an ordeal.

‘You will have to get used to ordeals like that,’ his sister Augusta, who was a year older than he was, told him brusquely, and he knew she was right.

But it passed off well. He did what was expected of him and no one remarked that he was shy and gauche; and his voice was quite steady when he pronounced that his little brother was to be called Frederick William.

That year they played the tragedy of Lady Jane Grey in the theatre of Cliveden. Nicholas Rowe had written it very appealingly and there were tears shed when the lovely Jane was led to the executioner’s block.

There was the excitement of rehearsals and learning one’s part; and Uncle Bute was so very good at anything concerning the theatre.

He was constantly with the family and Edward and Augusta whispered that many unkind things were said about him, but George could not believe that anyone could find anything unkind to say about Uncle Bute.

Papa was as fond of him as Mamma was. He was always saying, ‘Where’s Bute?’ And when he said he wanted to walk in the gardens with Lady Middlesex he would tell Lord Bute to accompany the Princess. Papa and Lady Middlesex would disappear for quite a long time, ‘walking the alleys’ as Papa called it. Mamma seemed very happy at such times because she did so enjoy walking with Uncle Bute. Although Papa and Lady Middlesex disappeared for a while Mamma and Lord Bute could be seen together in the gardens, always talking and laughing together, Mamma’s voice a little higher, a little more German as it was when she was pleased or excited. And then after a very long time if Papa appeared with Lady Middlesex the four of them would be very contented together.

Once when Uncle Cumberland called to see them he came to the nursery as he had on that other occasion and George had shrunk from his embrace because he could not stop thinking of him as The Butcher. He was aware of the sword at his uncle’s side, and in his imagination George saw it dripping with blood.

Uncle Cumberland was aware of this change in his nephew. He drew back in dismay. He said: ‘Oh my God, what have they told you about me?’

And he was too sad even to talk of wars.

George was sorry, for he hated trouble in the family.

When his father heard that the Duke had gone away he said: ‘Good riddance. We don’t want him here.’

Yet George could not believe his uncle was such a villain when he saw him face to face and he continued to think of him for a long time… sometimes as The Butcher with the sword dripping blood and others as the jolly uncle who was one of the most generous members of the family.

Papa was, he said, becoming a little anxious about their educations, and busied himself drawing up an account of how their lessons should be regulated.

They were to get up at seven o’clock and be ready to read with Mr Scott from eight until nine. Then they must study with Dr Ayscough from nine till eleven; from eleven to twelve Mr Fung must take over and from twelve to half past Mr Ruperti would be in charge. After that they could play until three, when dinner was taken. Mr Desnoyer came three times a week at half past four to instruct them in music; and at five they must continue the study of languages with Mr Fung until half past six. At half past six until eight they must be with Mr Scott again; at eight they took supper and must go to bed about ten o’clock. On Sundays George and Edward would be instructed by Dr Ayscough, with their two sisters, on the principles of religion.

This was a rigorous timetable and one which was not closely adhered to. It was typical of Frederick that having drawn up a list of stern rules he could feel he had done his duty, and when he decided that a game of tennis or cricket would be good for the boys, or it was time they performed another play, he happily interrupted the curriculum he had so carefully arranged.

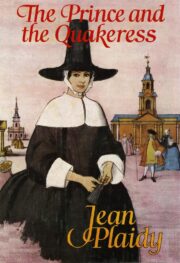

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.