‘You are very vehement, Mr Pitt.’

‘Not more so, Sire, than the occasion requires. Now, will you allow me to advise you on this one sentence. The rest of your speech stands as it is written. It is well enough. But this sentence must be adjusted. Now allow me… Instead of “bloody and expensive war which I shall endeavour to prosecute in the manner most likely to bring an honourable peace… ” we will say “ . . . an expensive but just and necessary war. I shall endeavour to prosecute it in a manner most likely to bring an honourable and lasting peace, in concert with my allies.” Now, will Your Majesty agree?’

George hesitated. He saw the point. It was true that Mr Pitt was leading the country to a position it had never before attained. But Lord Bute had said they must do without Mr Pitt because Mr Pitt would not be content to work under their direction. Mr Pitt would want to rule and lead them. All the same, there was something about the man which made it impossible to rebuff him.

‘I will consider it,’ said George haughtily.

Mr Pitt bowed and left.

It is the Scotsman who was trying to influence the King, thought Pitt. We shall have to delegate him to some position with a high-sounding name to hide its insignificance.

Without that evil genius George might be moulded into a fair shape of a King.

In a room at Carlton House the Archbishop of Canterbury received the members of the Privy Council when he solemnly informed them of an event which they already knew had taken place: George II was dead and they were assembled here to greet the new King, George III.

George, who had been in an antechamber waiting to be summoned, then came in.

In his hand he carried the speech he would deliver – his first as King of England. As he came to the Council Chamber his eyes met those of Mr Pitt. The minister’s were steely; he was wondering whether George would take his advice and change the speech which Bute had written. When he had been with the King he had been sure he would; but after speaking to Newcastle and talking together of the influence Bute had on the new King – and on his mother who also wielded great influence with the young man – he was a little uneasy.

He felt that what happened in the next few moments would be an indication and he would be able to plan accordingly.

Of one thing Pitt was certain; Bute would have to be relegated to the background, and the sooner the better.

George addressed his Council. At least, thought Pitt, they have taught him to speak. The new King enunciated perfectly – trained by actors. How different from his grandfather with his comical English, and his great-grandfather who couldn’t speak a word of the language!

There were great possibilities in George, Pitt decided. A young King could be an asset, providing he were malleable and had good ministers. This was a situation which Mr Pitt was sure prevailed but unfortunately there was Lord Bute… like a black shadow, an evil genius to undo all the good the auguries promised without him.

The King had started to speak: ‘The loss that I and the nation have sustained by the death of my grandfather would have been severely felt at any time; but coming at so critical a juncture and so unexpectedly, it is by many circumstances augmented, and the weight now falling on me much increased. I feel my own insufficiency to support it as I wish; but animated by the tenderest affection for my native country, and by depending upon the advice, experience and abilities of your lordships; on the support of every honest man; I enter with cheerfulness into the arduous situation, and shall make it the business of my life to promote in every thing, the glory and happiness of these kingdoms, to preserve and strengthen the constitution in both church and state; and as I mount the throne in the midst of an expensive, but just and necessary war I shall endeavour to prosecute it in a manner most likely to bring an honourable and lasting peace, in concert with my allies.’

Listening intently, Mr Pitt permitted himself a slow smile of triumph.

In the streets the people were still rejoicing. The old man was dead, and in his place was a young and handsome boy, who had been born and bred in England – a real Englishman this time, said the people. This was an end of the Germans.

There was feasting in the eating houses and drinking in the taverns and dancing round the bonfires in the streets. They knew what this meant. A coronation; that meant a holiday and a real chance to celebrate. And then there’d be a marriage, for the King was a young man and would need a wife.

This was a change, when for so long the only excitements had been the victory parades. It was stimulating to sing Rule Britannia, but wars meant something besides victories. They meant taxation, and men lost to the battle. But a coronation, a royal wedding… they were good fun. Dancing, singing, drinking… free wine doubtless… and sly jokes about the young married pair.

Now the people had their King they wanted a bride for him.

Pitt was congratulating himself over the matter of the speech. Bute would be an encumbrance; they would have to deal tactfully with him, but they would manage.

It was a shock when the day after George had been proclaimed King at Savile House, Charing Cross, Temple Bar, Cheapside and the Royal Exchange, to learn that the new King’s first act was to appoint his brother Edward and Lord Bute Privy Councillors.

‘There will be trouble,’ said Pitt. ‘Bute is going to make a bid for power. But I can handle him. The only thing I fear is that the King, through that fool Bute, will try to interfere with my conduct of the war.’

The war! It was Pitt’s chief concern. As long as everything went well on the battle-front, as long as he could succeed in his plans for building an Empire, events at home could take care of themselves.

At seven o’clock in the evening of a dark November day George II was buried in Henry VII’s chapel at Westminster.

The chamber was hung with purple, and silver lamps had been placed at intervals to disperse the gloom. Under a canopy of purple velvet stood the coffin. Six silver chandeliers had been placed about it and the effect was impressive.

The procession to the chapel was accompanied by muffled drums and fifes and the bells tolled continuously. The horse-guards wore crepe sashes and as their horses slowly walked through the crowds their riders drew their sabres and a hush fell on all those who watched.

Perhaps the most sincere mourner was William, Duke of Cumberland. He was in a sad state himself, for soon after he had lost the command of the army he had had a stroke of the palsy which had affected his features. Newcastle was beside him – a contrast with his plump figure and ruddy good looks. He was pretending to be deeply affected, but was in fact considering what effect the King’s very obvious devotion to Lord Bute was going to have on his career.

He wept ostentatiously – or pretended to – and as soon as he entered the Chapel groped his way to one of the stalls, implying that he was overcome by his grief; but he was soon watching the people through his quizzing glass to see who had come, until feeling the chill of the chapel he began to fret that he might catch cold.

‘The cold strikes right through one’s feet,’ he whispered to Pitt who was beside him.

Pitt did not answer; he was thinking how unfortunate it was that the old King had not lived a year or so longer to give him the security of tenure he needed. But it was absurd to fear; no one could oust Pitt from his position. Whatever Bute said the King would realize the impossibility of that. The people would never allow it for one thing. No, he had nothing to fear.

There was the young King, looking almost handsome in candle-light. Tall and upstanding, and that open countenance which was appealing. The King was honest enough, there was no denying that. The point was how much had that mother of his and her paramour got him under their thumbs?

The King was thinking: Poor Grandfather! So this is the end to all your posturings and pretence and all your anger. You will never be angry with me again, never hit me as you did in Hampton.

I will do everything you wished. I have heard that you, burned your father’s will and that he burned his wife’s, but I shall carry out your wishes to the letter. Lady Yarmouth shall have what you wished her to. I want to be a good King, Grandfather. Perhaps you did too. But you cared too much for Germany, and a King of England’s first care should be England.

Poor Uncle William! How ill he looked. It was sad when one recalled his coming to the nursery in the old days and talking about the’45. That was the highlight of his life, poor Uncle William; that terrible battle of Culloden had been his glory. And then he had lost his power and after that his illness had come, and now – although he was not very old when compared with his father the dead King – he was a very sick man. Yet he stood erect, indifferent to his own disabilities, and if one did not see how distorted his face was, which was possible in this dim candle-light, he looked a fine figure of a man in his long black cloak, the train of which must be all of five yards long.

The Duke of Newcastle was bustling about. Dear Lord Bute was right. That man was a fool and no use to them at all. If only he could be as sure that they should rid themselves of Mr Pitt! There stood Newcastle, crying one moment, looking round to bow to someone the next, shivering with cold and whispering that he would be the next one they were burying, for there was no place more likely for catching one’s death than at a funeral, and the Chapel of Henry VII must be the coldest place on Earth.

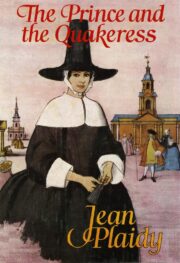

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.