But there was one he needed; and it was of him he first thought.

He told the messenger he might return whence he had come and turning to his groom he said: ‘Take the horses back to the stables and say one has gone lame. You have seen the messenger from the King. Tell no one you have seen this… if you value your employment.’

‘Yes, Your Highness.’

The Prince dismounted and made his way to the apartments of Lord Bute.

His lordship was at breakfast and as soon as he saw George he knew what had happened.

He hastily dismissed his servants and, kneeling, kissed George’s hands.

‘Long live the King!’ he cried. ‘And a blessing on Your Majesty.’

‘Whose first command will be to hold you to your promise, my lord.’

‘My life is at Your Majesty’s service.’

‘Now,’ said George, ‘I feel competent to mount the throne.’

While the new King and Lord Bute were preparing to leave for London, a letter arrived for George in the hand of his Aunt Amelia.

George took it and read it. It formally announced the death of her father and begged George to come to London with all speed.

Bute watched his protégé sign the receipt for the letter, boldly and without hesitation: G.R. A King of twenty-two, thought Lord Bute. That could be an alarming state of affairs – but not with George, innocent malleable George.

‘Your Majesty is ready?’ he asked when the messenger had gone.

George answered: ‘Let us leave.’

There was certainly a new purpose about him. The lessons had been taken to heart. How different it would have been if that extraordinary affair of the Quaker had not been satisfactorily settled. Bute grew cold at the thought. That had been a narrow escape from disaster, brought about just in time.

On the road from Kew they discussed the new position. George would have to be firm; he would be surrounded by some very ambitious men; and the most formidable of them was, of course, Mr Pitt.

The sound of horses’ hooves made Bute put his head out of the carriage window.

He sank back in his seat grimacing. ‘As I thought. They have lost little time. Mr Pitt is on his way to Kew.’

Mr Pitt’s splendid equipage with his postilions in blue and silver livery and his carriage drawn by six fine horses had pulled up beside the royal coach. Mr Pitt alighted – perfectly groomed, his tie wig set neatly on his little head, his hawk’s eyes veiled but glittering.

‘At Your Majesty’s service.’

‘You are kind, Mr Pitt,’ said George.

‘As soon as the news was brought to me I set out for Kew to offer my condolences for the loss of your grandfather and my congratulations on Your Majesty’s elevation to the throne. There are certain immediate formalities and I have come prepared to advise Your Majesty on the way to London.’

Pitt was ignoring Bute as though he were some menial attendant. Bute could say nothing in the presence of the King, but his fury was rising. George, however, had indeed been well trained.

‘Thank you, Mr Pitt,’ he said, ‘but I shall give my own orders and am on my way to London to do so. I suggest that you get into your carriage and follow us.’

Pitt was amazed. He had expected to ride with the King into London. He had thought the young man would naturally have turned to him for guidance. Moreover, it was the custom for the King’s ministers to advise the King; and here was this boy – twenty-two and young for his years – telling the Great Commoner himself that he had no need of his services.

For once Pitt was at a loss for words. He bowed; got into his carriage and while the King and his dear friend Lord Bute rode on towards London, Mr Pitt had no help for it but to get into his carriage and follow.

Bute was laughing with glee as they rode along.

‘I fancy Mr Pitt is very surprised. He thought Your Majesty would almost fall on your knees before him. He has to be shown his place.’

‘We will show him,’ said George.

‘His position is not exactly a happy one,’ smiled Bute, ‘for although he has taken power into his hands it is still that dolt Newcastle who is the nominal head of the government. That will make it easier. Your Majesty should summon Newcastle… not Pitt. Then our arrogant gentleman will realize that Your Majesty has no intention of being ruled by him.’

Indeed not! thought George. He would not be ruled by anyone. He was King. It was what he had been born for… reared for… and now he had reached that high eminence.

He looked at the countryside with tears in his eyes. His land! These people whom he saw here and there, did not know it yet, but they had a King who was going to concern himself only with their welfare. He was going to make this a great and happy country. He and his Queen would set an example of morality which would take the place of all the profligacy which had darkened the country before.

His Queen. He saw her clearly beside him. The loveliest girl in the kingdom – who but the Lady Sarah Lennox?

Pitt, regarding the new King’s strange behaviour on the road as youthful arrogance and uncertainty, arranged for the first meeting of the Privy Council to be held at Savile House. Meanwhile George, under Lord Bute’s direction, had sent for the Duke of Newcastle to wait on him at Leicester House.

There the new King told Newcastle that he had always had a good opinion of him and he knew his zeal for his grandfather and he believed that zeal would be extended to him.

Newcastle expressed his pleasure and was looking forward to telling Pitt that their fears regarding the new King were unfounded, when George said: ‘My Lord Bute is your good friend. He will tell you my thoughts.’

Newcastle was bewildered. He had always known of the young King’s fondness for Bute, but he could not believe it would be carried as far as this. He might regard the Scotsman as a parent, but surely he realized the heights to which Pitt had carried the country.

He left the King’s presence and went to see Pitt to impart his misgivings to him.

Pitt agreed that the King’s conduct was extraordinary.

‘But we must not forget,’ he reminded Newcastle, ‘that he has been ill-prepared for his destiny. When he is made aware of the position he will be easy enough to handle. I have prepared the speech he is to make to the Council and was about to leave to see him now.’

‘I will await your return with some misgivings,’ the Duke told him.

Pitt bowed before the King.

He smiled and went on to say that he doubted not the King knew the procedure on occasions such as the present – ‘of which, Your Majesty, there have been many in our history’.

‘I am acquainted with the procedure,’ said George coolly, for Bute had told him that the only way to deal with Mr Pitt was to refuse to see him as the great man Mr Pitt believed himself to be. Pitt was the King’s minister and he had to be made to see that he was not the King. ‘A misapprehension,’ added Lord Bute, ‘that his manner would suggest he deludes himself into believing.’

‘I guessed Your Majesty would be, and I have prepared your speech. Perhaps you would look over it and give it your approval?’

George replied as Bute had suggested he should, because Bute had known that Pitt would present himself and his speech at the earliest possible moment. In fact Bute had already prepared the speech, so George had no need of Mr Pitt’s literary efforts.

‘I have already viewed this subject with attention,’ said the King, ‘and have prepared what I shall say at the Council table.’

Pitt was astonished. Ministers had grown accustomed to the indifference of Hanoverian kings to the traditions of English monarchy. And here was a boy – twenty-two years old – flying in the face of custom.

‘Your Majesty would no doubt allow me to glance over what you intend to say.’

George hesitated. Bute had not advised him on this point. He said: ‘Er… yes, Mr Pitt. You may see it.’ And going to a drawer he produced the speech.

Mr Pitt cast his eyes over it and when he came to the phrase ‘. . . and as I mount the throne in the midst of a bloody and expensive war I shall endeavour to prosecute it in the manner most likely to bring an honourable peace…’ Mr Pitt paused; his eyes opened wide and a look of horror spread over his face.

‘Your Majesty, this cannot be said.’

George was alarmed, but he endeavoured to follow Bute’s instructions and preserve an aloof coldness.

‘Sire, this war is necessary to our country’s well-being. Our conquests have raised us from a country of no importance to a world power. I recall Lord Bute’s writing to me a few years ago when he deplored the state of our country in which he saw the wreck of the crown. Lord Bute was right then, Sire. Later he was congratulating me on our successes and thanking God that I was at the helm. I venture to think his lordship cannot have changed his mind since his hopes in my endeavours have not proved in vain. This war is bloody, Sire. All wars are bloody. It is not unduly expensive, for in spite of its outlay in men and money it is bringing in such rewards, Sire, as England never possessed before. You will not be a King merely; you will be an Emperor… when India and America are yours. And believe me, Sire, there is untold wealth, untold glory, to come your way. So I beg of you do not rail in your first speech as King against a bloody and expensive war.’ George was about to speak, but Pitt held up a hand and without Lord Bute at his side to guide him George could only listen. ‘One thing more I am sure Your Majesty has overlooked. You have allies. Are you going to make a peace without consulting them? Believe me, Sire, that if you use these words in your first speech to your Council you will do irreparable harm to yourself and your country.’

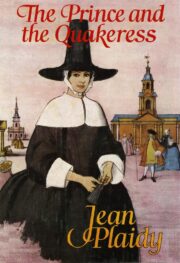

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.