She is beautiful, thought George. One day I will speak to her.

He became obsessed by her. He forgot Hannah and to mourn for Elizabeth for he could not be unhappy in a world which contained Lady Sarah Lennox.

His eyes were always on her. One day he approached her.

‘I know who you are,’ he told her. ‘You are Lady Sarah Lennox.’

‘How discerning of Your Highness! I also know who you are, but that is not very clever of me, is it? Since everyone knows Your Highness.’

‘I am sure you would be clever.’

‘Oh, does Your Highness think so? It is more than some people do.’

‘What people?’

‘Oh… one’s family.’

He was very grave. ‘I hope your family appreciates you.’

‘About as much as yours do, I expect. You know what families are.’ She laughed and he found the conversation scintillating. She was a little arch, having known for some time of the effect she had on him and being amused to find a Prince of Wales so shy in the company of a girl who although the sister of the Duke of Richmond, and more important still the sister-in-law of Henry Fox, was of little real significance in the exalted company of the Prince of Wales.

‘Oh yes,’ he said, laughing with her. ‘I know. I have watched you dancing… often.’

‘Yes, I know. I have seen you watching.’ And she laughed, and he laughed with her. ‘Your Highness does not care for dancing?’

‘Oh, I would not say that.’

‘I have not seen you dance.’

‘What was the dance I saw you dancing a few moments ago?’

‘The Betty Blue – surely Your Highness knows it?’

‘I confess I do not.’

‘Why, la! It is the latest fashion.’

‘I have never danced it.’

‘Your Highness should. It is highly diverting.’

‘One needs to be skilful.’

‘Nonsense. Oh…’ She put the slenderest of fingers to the prettiest of mouths. ‘Now you will be angry. It’s lése majesté or something. I told the Prince of Wales he was speaking nonsense.’

‘It does not matter. I… I am sure you are right.’

‘Is Your Highness sure?’ Her lovely eyes were wide open. What he was uncertain of was whether she were serious or not. ‘Your Highness is not going to send me to the Tower?’

‘Not unless you allow me to come with you.’

She laughed again. Nobody ever laughed as she did, he was sure. So gay, so spontaneous, so joyous. It made him want to laugh too.

‘And there,’ she went on, ‘I would teach you the Betty Blue.’

‘It is not necessary to go to the Tower to teach me that.’

‘Your Highness means that I should teach you here?’

‘Would you… would you object to that?’

‘Why, if Your Highness commanded I could not object.’

‘I would not wish to command you.’

‘Then, sir, I will say it would give me the greatest pleasure to teach you the steps of the Betty Blue.’

So she taught him – touching hands, coming close; parting and coming together again. It was bliss, thought the Prince of Wales.

He had never been so happy in his life… except with Hannah, he hastily told himself. But he must be truthful. With Hannah there had always been the sense of guilt. There was none of that with Sarah. He could dance with her, talk with her, laugh with her – and people looked on smiling at them.

Yes, this was sheer bliss.

At first the morning of the 25th October of the year 1760 seemed like any other in the King’s apartments at Kensington. The King had slept well and on the stroke of six precisely rose from his bed; as usual he asked his valet in which direction the wind was blowing. The valet always had the answer ready, for the King would be testy if he had not. And it must be correct. Then he would look at his watch and compare it with all the clocks in the apartment. There were several, for time was one of the most important factors of the King’s life.

He sat in his chair and waited for his cup of chocolate. It must arrive exactly to the minute; and it must be neither too hot nor too cold. His servants knew how to please him and he rarely had cause to complain, although when he was in a bad mood he could find many reasons. Schroder, his German valet, understood him well. ‘Germans make the best servants,’ he was apt to say; just as he said: ‘Germans are the best cooks, the best soldiers, the best friends…’

‘So the weather is good this morning, Schroder,’ he said as the dish of chocolate was handed to him and he had heard the report on the wind.

‘Yes, Sire. Some sun and pleasant for walking.’

‘I shall take a walk in the gardens. Plenty of exercise, Schroder, and never guzzling at the table.’

‘Yes, Sire.’

‘That’s the way to prevent getting too fat. I used to tease the Queen about her weight. Oh, she loved her chocolate, Schroder. Could not resist it. And she was a woman wise in every other way. I was always telling her she should eat less. There’s a tendency to run to fat in the family, Schroder.’

‘Oh yes, Sire.’

‘That clock is almost a minute slow.’

‘Is it, Sire? I will speak to the clock winder without delay.’

The King nodded.

But he was feeling in a jovial mood, not inclined to be angry about the clock. He was thinking of Caroline, sitting at breakfast with the family, and Lord Hervey hovering. An amusing fellow, Hervey, and a great favourite with Caroline. And all the children there. Not many of them left now. Fred had gone… no loss. And William his only other son a disappointment to him. Emily a sour old spinster. They ought to have let her marry. Just those two left to him, William and Emily… both unmarried. He couldn’t count Mary who’d married the Land-grave of Hesse-Cassel. She was too far away. Not much of a family, then. And the boy… George! He would be all right if he could cut loose from his mother’s apron strings and free himself from the Scotsman.

It would have been different if Caroline had lived. He always thought of Caroline in the mornings; in the evenings he devoted himself to the Countess of Yarmouth. She was a good woman and he was glad he had brought her from Hanover. Caroline would be pleased, he told himself. She was always fond of those who were fond of me.

He looked at the clock, drained off his chocolate and rose to go into the closet. It was a quarter past seven.

He shut the door and suddenly he felt a dizziness; he put out his hand to the bureau to steady himself, and as he did so he fell to the floor.

Schroder had heard the fall and ran into the closet; he saw the King lying on the floor, and that he had cut his head on the side of the bureau.

‘Your Majesty, are you all right?’

There was no answer. He knelt down and cried: ‘Mein Gott!’

Then he called to the other servants.

‘His Majesty…’ he stammered; and they lifted the King and laid him on the bed.

‘Call the physicians,’ cried Schroder; and at that moment Lady Yarmouth came running in.

‘Schroder. What has happened? Where is the King? Oh my God!’

‘His Majesty fell, while in his closet,’ Schroder told her. ‘I have sent for the doctors.’

Lady Yarmouth knelt by the bed murmuring: ‘Mein Gott! Mein Gott!’

When the doctors came they said they would bleed the King without delay, for it was certain that he had had a stroke. But when they tried to bleed him, no blood came.

Schroder knew what that meant. The King was dead.

Schroder also knew his duty. He had been primed in it by Lord Bute and although he served the King loyally he was not such a fool as to believe that he must ignore the masters of tomorrow for the rulers of the day.

Lord Bute had said: ‘It is imperative that if anything should happen to the King – and he is in his seventy-seventh year so it’s not unlikely – the first to know should be the Prince of Wales. It is your duty, Schroder, to see that is done. So in this unhappy event send a message immediately to His Highness and do not say “The King is dead”. Write that he has had an accident… an accident will mean that he is dying; a bad accident will imply that he is dead.’

Those orders were clear enough and it was also clear to a man of Schroder’s intelligence where the orders would come from from now on.

So while the doctors busied themselves about the bed and Lady Yarmouth knelt by the bed in a state of dazed apprehension, Schroder wrote on the first piece of paper he could find that the King had had a bad accident and he despatched a messenger with it to Kew, with the instructions that it was to be put in no hands except those of the Prince of Wales.

George was taking his morning ride in the gardens at Kew when he saw the messenger in the King’s livery riding towards him.

He pulled up and waited. His heart had begun to beat faster. He guessed, of course. They had been waiting for it so long; it had to come sooner or later and there could be no denying that here it was when he read Schroder’s scrawl: ‘Your Highness, the King has met with a serious accident.’

In those first seconds George was aware of a terrible sense of isolation. This brisk October morning was different from any other in his life. He had changed. He was not the same man he had been yesterday. He had become a King.

He shivered a little. He had visualized this so many times, but nothing is quite the same in the imagination as in reality.

There was such a mingling of emotion – fear and pleasure, pride and apprehension; a sense of power and of inadequacy.

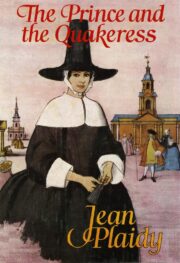

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.