The one person to whom he could most easily talk was his sister Elizabeth and he went to her room as much as possible. She was spending almost the whole time in bed, for she was more easily fatigued than ever. When he expressed anxiety over this she would smile and say: ‘It’s a miserable old body, George. But never mind. Such as I have to live for the spirit.’

And what a spirit she had. She never complained; her face would light up with joy when he visited her, as though he were conferring an honour; he felt humble in her presence and at the same time completely at ease.

He could tell her of the dreams. She listened with rapt attention. ‘As time passes they will cease to haunt you,’ she assured him.

Once she told him – this was some time after that visit to Islington when he had ceased to think of Hannah every moment of the day: ‘George, perhaps it was for the best.’

‘For the best!’ He was aghast.

‘Oh, my dearest brother,’ she begged, ‘imagine it. You, the Prince of Wales… to have married in this way. The people would never have accepted her.’

‘If you had known Hannah… She was so good… so gentle…’

‘I know, George, but they expect a Prince… a King… to marry a Princess, and do you think Hannah would have been happy… as a Queen! Imagine all the scandal, the intrigue. It was no life for her. No, George, I think she would have been unhappy, and you would have been unhappy to see her so. I know it seems hard to accept now, but I do believe that everything has happened for the best. The children are well cared for. You have seen them?’

‘Yes,’ said George. ‘They seem to have accepted their new parents without question.’

‘Children do. Thank God that they are so young. And perhaps in time you will come to thank Him for the way everything has turned out.’

‘Never,’ cried George.

But Elizabeth was sure; and she knew something which he did not; he was already growing away from the tragedy. If, she thought, he could have said goodbye to her, if he could have given her that last embrace at her death-bed, if the affair could have been neatly labelled ‘Finished,’ it would have been easier to forget.

Mysteries have long lives, thought Elizabeth.

Elizabeth Chudleigh was in a quandary. She had very successfully skated over the thin ice of her relations with the Princess Dowager. The Princess avoided her as much as possible, but when they did encounter each other was coolly affable. I am safe there, thought Elizabeth grimly.

But her luck was out – or was it? She could not make sure. Clever people never waited for luck to come their way; they find a means of making it do so. That was the way she had always worked.

She had her certificate of marriage; the entry was safe in the register; but that irritating old man the Earl of Bristol refused to die. In fact he had recovered and looked as though he would continue to survive for several more years.

‘And I do not grow younger!’ sighed Elizabeth. She had to admit she was well past her first youth. While one remained in the lower thirties one could, if one were clever enough, continue to be young, but when one hurried towards forty… ugh! And she still had not the title she longed for.

A complication had arisen from another direction. A certain gentleman had been casting his eyes on her and she had no doubt that he was becoming definitely dazzled. This was amazing, for he was not young and was scholarly, not the kind to indulge in riotous living; yet he was definitely interested in her – and she in him… he because she was one of the most unusual women at Court, one of the most beautiful – most people would admit that – and one of the most outrageous. And she because of his exciting title. He was Evelyn Pierrepont, Duke of Kingston.

But she had told the Princess Dowager of her marriage to Hervey. She had gone to Larnston and forged the certificate and made that old man Annis reinstate that page in the register. What bad luck. If only the Duke of Kingston had come into her life before she had done that.

Now what? Old Bristol clinging tenaciously to life and seeming to be good for years yet; and on the horizon the most glittering prize – the Duchess of Kingston.

She admired her bold adventuring spirit, but she had always admitted that there was one quality which had brought her trouble more than once: her impulsiveness.

She must curb that. Then she would not mention her marriage to anyone else. She would imply to the Princess Dowager that she wished it kept a secret; and that lady must obey because she, clever Elizabeth Chudleigh, knew so much that the Princess would not wish to be brought to light. Then she would very gradually enslave the Duke of Kingston – being reluctant at first, but not too reluctant – leading him on, yet holding him off. She had summed him up. He was not accustomed to women – not women such as herself, in any case. Perhaps she would become his mistress… in due course. And once she had done that she would make herself so necessary to him that he would wish for marriage.

The Duchess of Kingston! It was a pleasant title. She preferred it to the Countess of Bristol. It would have to be fought for, but then, she had always enjoyed a fight. And the dear silly young Prince had put all the trump cards into her hand, so she had all the advantages. All she had to do was curb her recklessness and the game was hers.

September had come. George was at Kew a great deal in the company of Lord Bute; they rode together and constantly they talked of the future. In this way, contemplating his great destiny, George thought less of Hannah. He was beginning to realize, although he would not admit this even to himself, that Elizabeth was right when she had said that Hannah would not have been happy at Court. More and more he understood that. When he considered how much he had to learn – he who had lived all his life at Court – he saw at once that Hannah would never have fitted in.

But he could not bring himself to admit that everything had turned out in the best way possible. Bute had hinted at it once or twice.

‘There will always be Jacobites,’ he had said, on one occasion. ‘One of the most dangerous blows that can be struck at a crown is to have more than one claimant. And if a family divides as yours did when James II was turned from the throne by his nephew William of Orange and his daughter Mary, there is sure to be trouble. Remember the’45. It is not so far back. Then your grandfather might so easily have had to retire to Hanover, leaving England in the hands of the Stuart.’

‘James II deserved his fate, I believe. He would not conform to the wishes of the people.’

‘Ah, I see Your Highness has learned his lessons. One must strive to keep the goodwill of the people. One must never put oneself in the position of earning their disapproval. It is so easily done. One false step…’

George flushed and patted his horse’s head. He knew what Lord Bute meant. The marriage with Hannah could have been as fatal to the crown as James II’s religion. One had to be careful.

He wanted to be a good King. It was strange how accustomed to the idea of kingship he had grown. At one time the prospect had terrified him. He had even wished he had been born a younger brother… or perhaps of another branch of the family… perhaps not royal at all. Lord Bute’s son. That would have been pleasant. But then, Lord Bute spent more time with him than he did with any of his own family.

Now, however, with every day he was becoming more and more accustomed to the prospect of ascending the throne. And during that summer and early autumn he found that he was dedicating himself to an ideal; it gave a new meaning to life. It was the best possible means of forgetting Hannah.

A message was brought to him that his sister Elizabeth wished to see him without delay.

He hurried to her and found her in bed, wan, frail and in pain.

‘My dearest sister, what is wrong?’

‘Oh, George, how glad I am that you have come. I am in great pain… and I believe I am about to die.’

‘This is nonsense. Where are the doctors?’

‘They are in the anteroom. I told everyone that I wished to be alone with you.’

‘Then we will be together, but do not talk of dying because that is something I cannot endure.’

‘We have always been good friends, have we not, George?’

‘The best. You are going to be well. I shall see that you are. I shall be with you… night and day. Nothing will induce me to leave you.’

‘My dearest of brothers, my greatest regret is to leave you.’

‘Stop! You are not leaving me.’

‘I am in such pain, George. They say it is an inflammation of the bowels… but I do not know.’

‘Can they do nothing?’

She shook her head. ‘I believe they have given me up.’

‘This cannot be. Not you… too… Elizabeth.’

‘You still mourn for her, George?’

He nodded.

‘Please, try not to be too sad, brother. Life is too short for sadness. Mine was. I am eighteen and you are three years older. It is young to die… but I am not sorry to go. It was a poor body, mine. It gave me no pleasure to look at it. My soul is glad to leave it. Poor humped miserable flesh and bone.’

‘Do not talk so, Elizabeth.’

‘I wish to cheer you, brother. I want you to know that nothing is entirely bad. I am leaving this life, but although I shall be lost to those I love – and particularly you, George, I leave this malformed body of mine. I shall be free. I shall be as a bird which has just found her wings. Think of that, George, and do not be too sad. You have a great destiny before you. You will be King of England. And you will be a good king because you are a good man. Perhaps I shall be looking down on you from Heaven. Oh, George, if it were in my power to guide you, to help you… I should do it. Now you are weeping. You grieve to see me go. But do not grieve for me, George, and do not grieve for Hannah. It is for the best, I assure you it is for the best… everything that has happened.’

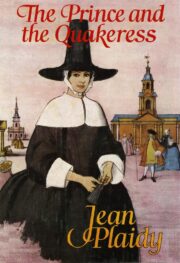

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.