She came and stood beside him.

‘Thou art a very clever artist,’ she said.

He was quick to notice the form of address. A Quakeress, he thought. Of course! Why did I not realize it before? From then on he began to think of her as the beautiful and mysterious Quakeress.

He could not tempt her to speak of herself when she so clearly did not wish to do so. Instead he found himself talking of his own life.

She was very interested and as he talked she became animated. She was living the scenes he described as surely as though she had been present when they had happened; it brought a new animation to her face.

He told her about his home at Plympton Earl in Devonshire. He talked of the beauties of Devon, the coast, the wooded hills and the rich red earth… all exciting in the artistic eye.

‘But it was always portraits which fascinated me… people. Landscape is exciting but people are alive . . . They present one face to the world, but there is another which is perhaps truly themselves. One other? There are a thousand. A thousand different people in that one body. Think of that, Mrs Axford.’

‘Are we all so complex, then?’

‘Every one of us. Yourself, for instance; you are not solely the charming hostess to a painter, are you. You are many things beside.’

‘Yes, I see. I am good and I am wicked. I’m truthful and I lie. My life is beautiful and hideous…’

‘And you live here in this comfortable house, a lady of fashion…’

‘Never that. How could I be when I don’t…’

He waited hopefully, but she merely added: ‘Never a lady of fashion.’

‘Yet not a Quakeress?’

‘Why did you say that?’

‘You were once a Quakeress, were you not?’

‘Yes. I betrayed it.’

‘Don’t forget I am an artist. I try to discover all I can about a sitter so that I can see her not only as the world sees her but as she really is. You look alarmed. There is no need. I am sure that I should never see anything of you, Mrs Axford, that was not admirable.’

‘You flatter me.’

‘I never flatter. That is not the way to produce great art.’

She fell silent and to bring back her serenity he talked about himself.

‘I always knew I wanted to be an artist. My father was a clergyman. He was master of the grammar school too. I had a religious upbringing.’

Her eyes glowed with understanding. He pictured the austere Quaker household. Poor girl, she must find it difficult to escape from such an upbringing. And what courage she must have, what a deep love she must have felt, to have risked eternal damnation – for that would be what she would have been led to expect – by setting up house with a lover.

‘But I wanted to paint,’ he went on, ‘and at last my father understood there was no stopping me. So he sent me to London and apprenticed me there to Thomas Hudson. He was a Devon man settled in London.’

‘And you learned to paint?’

‘I learned to paint and I was happy. And when I had served my apprenticeship and thought myself a fully fledged portrait painter I came back to Devon, settled at Plymouth Dock and started to paint portraits. But it was no use. I had to return to London. It is the only place for a man of ambition.’

‘Thou wert ambitious.’

She was interested in his progress and had not noticed that once more she had slipped into the Quaker form of address. He found it charming on her lips. How I wish I were painting her in Quaker gown and bonnet. She does not need white satin and blue bows, with beauty such as hers.

‘I was ambitious, so back to London I came, where Thomas Hudson introduced me to many artists. I joined their club… the. Artists Club. It meets at Old Slaughter’s in St Martin’s Lane. You know the place?’

‘I saw it often when I used to go…’

He waited. ‘So you lived near there?’

‘Yes, I lived near.’ She was shut up again. He wondered where the nobleman had found his little Quaker girl.

‘It was my painting of Captain Keppel which brought me many commissions. Then I went to Italy. All artists must go to Italy. Have you ever been, Mrs Axford?’

She had never left England, she told him.

‘Ah, you would love Italy. Perhaps Mr… Mr Axford will take you one day?’

A faint shiver touched her, and he was aware of it. It was no use trying to make her talk; he must rouse the animation he wanted to see in her by talking of his own life. So he talked of Minorca, Rome, Florence, Venice… and she was enchanted by his description of these places. He described with the artist’s eye… in colours, and she seemed to understand. Then he told her of his friends, Dr Johnson, Oliver Goldsmith, the actor Garrick.

‘There is not much support for the arts from the royal family. Let us hope young George will have a little more artistic sense and responsibility than his grandfather when his time comes.’

‘I… I think he will.’

‘They say he is not very bright, and, of course, Bute and the Princess have him in leading strings.’

‘Is that what they say?’

‘And it happens to be true. I have friends at Court. Oh well, they tell me he needs these leading reins. He’s only a boy… simply brought up… in fact, a simpleton. I wish they would teach him a little about art. I suppose they think that an unnecessary part of life. They’re wrong, Mrs Axford. A nation’s art and literature are a nation’s strength. We need a monarch who understands this. I wish I could have a talk with the young Prince. The King is too old now, but I had heard that he had a great contempt for poetry. Poor man. I pity him. Let us hope the new King will be different. For his own sake I hope so. Being a King is something more than marrying and producing children. I dareswear they’ll be marrying young George off soon. He’s of age. Time he had a wife.’

She was sitting very still and it was as though all the life was drained from her.

She was a woman of moods, he decided. And he wondered whether he had succeeded in getting what he wanted.

When he finished the picture he called it ‘Mrs Axford, the fair Quakeress’.

He received his fee through the ubiquitous Miss Chudleigh; and after a while he ceased to ponder on the strangeness of the mysterious Quakeress.

Rule Britannia

HANNAH HAD PRESENTED George with a son. He shared her delight and her fears. ‘If we were only married,’ he said, ‘I would be the happiest man alive.’

And she the happiest of women, she told him. But perhaps she did not deserve happiness. She thought often of her mother and the sorrow she had caused her; her uncle, too, but particularly her mother. She wondered if they still searched for her, mourned for her, prayed for her.

Dr Fothergill, blindfolded as before, had delivered the child; but she was not so well after this second confinement as the first; and when she was less well she was apt to brood more on her sins.

George had been delighted with the picture. He told her that Joshua Reynolds was the most fashionable painter in London and people of the Court were clamouring to have him paint their portraits.

‘I doubt he will ever paint a picture so charming as that of the fair Quakeress,’ said George gallantly.

She had two children, and visits from a lover whose affection never wavered; she could have been completely happy if their union had had the blessing of the Church.

It would be all I asked, she told herself.

George had to curtail his visits, for there was business to keep him occupied. Lord Bute scarcely let him out of his sight.

‘The King cannot last much longer,’ he told George. ‘Oh, my Prince, I want you to be ready when the time comes.’

‘I shall be, if you are beside me. Without you I should fail. I often think of what a dreadful situation I should be in if I ever had to reign without your assistance.’

Bute was delighted with such reiterated trust. It was worth the tremendous effort he had put into engendering it.

Pitt was the man of the moment. Bute pointed this out to George. The man was a giant. They had to remember that, and although they would relegate him to a minor position – Bute was determined to lead the government, that being the ultimate goal – they would continue to use Pitt.

‘Oh yes, we will use him,’ agreed George.

He was beginning to look forward to power. It would be pleasant never to have to suffer the humiliation of visits such as that one to Hampton which so rankled in his mind. He would be the King, and when he was no one would dare behave towards him as his grandfather had.

Great events were afoot. Mr Pitt was a brilliant war leader and under him England was going to be the leading country of the world. Mr Pitt believed it; and he was a man who always achieved his end.

But he was a just man and he was thundering in Parliament now over the execution of Admiral Byng for which shortly before the people had been clamouring; but now the deed was done they were mourning for him, calling his execution murder.

‘You perceive the unreliability of the mob,’ said Bute.

‘Hosanna, Hosanna… and shortly after crucify him,’ said George.

Bute smiled with approval. George was beginning to think for himself.

‘It is always difficult to do what the people want,’ went on Bute, ‘for their wants are rarely constant. Mr Pitt rails against the injustice.’

‘He is a good man, Mr Pitt. I remember how he defended my uncle Cumberland for being unjustly accused over Hanover. He was no friend of my uncle – and I doubt he was of Mr Byng’s.’

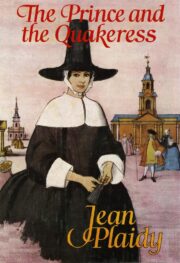

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.