The King looked at his watch. He did not intend to spoil this meeting with his mistress.

‘The puppy will have to be brought to heel,’ he said.

‘I am sure Your Majesty will soon have him where you wish him to be.’

This was her most attractive quality: she always made him feel a wise and great man. In fact he felt more comfortable with her than he had with Caroline, although he would not admit that now.

‘I’ll deal with him,’ he said; and shelved the matter as she had hoped he would.

What a soothing, tender creature she was. He was lucky to have found her!

The King wanted no trouble. He demanded that ‘secret papers’ be brought to him and he feigned to study them. He then announced that he thought better of the Duke of Cumberland than he had, and he believed that there was no need to continue with this farce of a resignation.

But the Duke was determined. He would treat his father with the respect due to a King, for he was a royalist by nature; and having seen the ill effects of quarrels on the royal family’s prestige he did not want to add to that.

He had nevertheless made up his mind that he could no longer talce a command in an army in which he was obliged to obey the orders from the Council and his father, and then take the blame when they were unsuccessful.

He had been deeply wounded; he saw only one course of action open to him: resignation; and nothing was going to prevent his taking it.

The Duke of Cumberland had resigned. The hero-villain of Culloden was no longer in command of the army.

His passion in life had been the army and now he was no longer of it. The action of his father had made it impossible for him to retain his position. But this was no family quarrel. The Duke robbed of his position, of his career through the action of his father, continued to pay him the utmost homage in public.

He now turned appealingly to his nephew. He hoped that the Prince of Wales would allow him to bestow on him that affection which he yearned to give.

The Princess and Lord Bute told themselves that they must watch the Duke of Cumberland.

Joshua Reynolds calls

THE PRINCE OF Wales was very proud of having a daughter and could not resist talking of her to those in the secret.

‘How I wish I could see her!’ sighed his sister Elizabeth.

‘And how I wish you could. Perhaps I could take you one day.’

‘Everyone would recognize my poor body if I attempted to call on her.’

‘If she met you she would love you as I do.’

‘I hope that one day I shall.’

‘I see no reason why I shouldn’t see her,’ declared Edward.

The Prince of Wales considered this. ‘No… I suppose not. Hannah might be a little reluctant. She is very retiring.’

‘Tell her I would not harm her. I should only love her… since you do.’

George beamed on his brother and sister with the utmost affection.

‘Have you ever thought of having that portrait painted?’ asked Elizabeth.

‘Who would paint it?’

‘Anyone would… if you asked them.’

‘Wouldn’t it be dangerous?’

Edward said: ‘If one is going to be afraid of danger one will never arrive at anything. It would not be one half as dangerous as abducting a Quakeress at the altar.’

‘I… I scarcely did that.’

‘Oh, come, brother, you are too modest.’

‘I have seen the work of Joshua Reynolds,’ said Elizabeth. ‘It is quite miraculous.’

‘I do not understand painting much…’ began George.

‘Elizabeth is right,’ corroborated Edward. ‘I have heard it said that he is the greatest living painter. None but the best would be good enough for the Prince of Wales.’

‘I should like her portrait to be painted,’ mused George.

‘Hush,’ whispered Edward. ‘Here comes our sister Augusta.’

Elizabeth began talking hastily about a piece of embroidery on which she was working. Augusta looked suspicious. A strange subject, she was thinking, for Elizabeth to discuss with her brothers. These three were always together, always seeming to share secrets, and Augusta had been told by her mother to try to discover what George talked about to his favourite sister and brother.

But, of course, they were silent as soon as she appeared. It was always so.

But George had something on his mind. It was obvious that he had some secret. She wondered what. It would be a triumph if she could discover it and report to her mother and Lord Bute. They would be so pleased with her.

George smiled at her absently. He had never greatly cared for his sister who was a year older than he was and apt to be resentful that she had not been born a boy, in which case all the honours which were his would have been hers.

George was thinking: Joshua Reynolds, why not?

A portrait, thought Hannah, as she dressed with the help of her maid. Thou hast become a vain and empty-headed woman Hannah Lightfoot.

She would not think of herself as Hannah Axford, and preferred to regard herself as a single woman rather than as that. She dreamed sometimes that Isaac Axford came to claim her, that he crept into this bedroom while she slept and that she awakened to find him standing over her.

The bedroom was becoming more and more ornate as the years passed. In the early days she had tried to keep it simple, for every now and then her upbringing would assert itself; then she would suffer terrible feelings of guilt and see the gates of hell yawning before her.

Had her marriage to Isaac been a true marriage? Sometimes she liked to think not. On the other hand, sometimes she must believe it was a true marriage when it seemed less shocking for a woman who had been through the marriage ceremony to have a lover, to be a mother, than for one to experience these things who had never been married at all. Then the thought of Isaac as a husband horrified her.

One fact was clear to her: she could never be truly happy. She loved her Prince; he was charming, never failing in his courtesy to her, giving her the respect he would have given to his Queen – yet the load of sin was on her, and she could never shift it.

And now a portrait.

She could imagine her uncle’s stern face if he knew. To dress herself in satin, to sit idly while her face was reproduced on canvas. What vanity. What sin.

But my sins are so many, she thought. What is a little vanity added to them?

In her nursery lay her daughter – her idolized child. Born in sin, she thought. What will become of her? But all must go well with her, for was she not the daughter of the Prince of Wales?

She had a suspicion that she was again pregnant. She had not told the Prince yet. She understood him so well and he was so good that their sin worried him as much as it did her, although he was not a Quaker and had lived his life at a Court which in Quaker circles was another name for debauchery.

What a beautiful gown this was! She thought of the day the seamstress had brought in the material and how it cascaded over the table in the sewing-room… yards and yards of thick white satin.

‘Oh, Madam, this will become you more than any of your gowns.’ And the woman had held it up to her and draped it round her and Hannah had swayed before the mirror, holding the stuff to her as though it were a partner in a dance. Then she had caught sight of her flushed face in the long mirror. Even such a mirror would have been considered sinful in her uncle’s home. And she thought: What have I come to?

But even so, she could not help being excited by the white satin and when the sewing-woman had made those enchanting blue bows with which to adorn it she had expressed her delight.

And now she was going to be painted in this gown by a great painter.

Her maid had slipped the white satin gown over her head and stood back to admire.

‘Oh, Madam, this is truly beautiful. The most beautiful of all your gowns.’

Hannah’s gaze returned to the mirror. I am always looking in mirrors, she told herself. Yet she could not look away.

She had changed since the child’s arrival; the hunted look was less apparent in her beautiful dark eyes. She was more serene. Odd, she thought, for the sin is greater now. I have passed on the sin to an innocent being and that my own child.

‘You like this dress?’ she said to the maid. She must remember not to use the Quaker thee and thou which slipped out now and then.

‘Oh, Madam, it is a miracle of a dress. But it needs a beautiful lady to show it off… and you are that.’

‘Thank you.’ She smiled gently. Yes, she thought. I am glad I am beautiful. And if I were meant to live humbly all my days in a linen-draper’s shop, why was I made beautiful?

It sounded like one of Jane’s arguments.

‘Tell them to let me know,’ she said, ‘immediately Mr Reynolds arrives.’

The painter’s carriage turned in at the private drive which led to the back of the house and was completely secluded. This was the drive George used when he came.

Some secret woman, mused Mr Reynolds, but he was not very interested in whose mistress this was, only whether she would be a good subject. He supposed she would have beauty of a kind, but he did not seek a conventional beauty. Nor did he wish to turn some woman, plain in the flesh, into a canvas beauty, which was often the expectation. He hoped for a subject who had something to offer, something on which his genius could get to work, so that he might reproduce her as a Reynolds portrait which would be apart from all other portraits which might be painted of her.

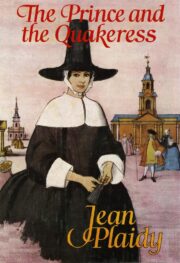

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.