But the elements were favourable and although Bubb went to the door of the tent and scowled up at the darkening skies, the rain persisted.

So in that tent she learned the background of this most fascinating man. He was thirty-four years old – six years younger than Fred – and had been born in Edinburgh. He was his father’s elder son and his mother had been the daughter of the Duke of Argyll. He had come south to Eton for his education and while there had met that gossip Horace Walpole; eleven years before this meeting in the tent he had married the daughter of Edward and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Augusta, who was conscious of such aspects, immediately thought that he would have married a pretty fortune there. His wife and family were in London now with him; and he had been driven to the races in a carriage which he had hired from his apothecary.

It was a stroke of good fortune, he remarked, that he had come and been so honoured as to have been invited into the tent.

Augusta was delighted to note that Fred was as interested in Lord Bute as she was – perhaps not quite so much, but then Fred was superficial by nature.

She believed that he, like herself, was a little dismayed when Bubb announced that the rain had stopped and they could now start on the homeward journey.

Lord Bute took his leave.

‘The Prince will wish you to call on us at Cliveden,’ Augusta reminded him; and Fred endorsed this.

Never, declared Lord Bute, had he received a command which gave him more pleasure.

‘We shall look for you… soon,’ Augusta reminded him.

He bowed.

‘And where is your apothecary with his carriage?’

‘Madam, he left an hour ago. That was the arrangement we made as he had business to which he must attend.’

‘And what shall you do now?’

‘Find a means of getting back to London.’

‘My lord!’ She was looking at Fred who was never one to fail in hospitality.

He was laughing. ‘We invited you to Cliveden, my lord,’ he said. ‘There’s no time like the present.’

What a pleasant journey. The rain had freshened the countryside, bringing out the sweet scents of the earth as they rode along, Lord Bute entertaining them on such subjects as architecture, botany and agriculture which had suddenly become quite fascinating.

But Frederick soon led him back to the theatre and that was the most interesting topic of all.

And so they came to Cliveden. What a pleasant day! thought Augusta, looking at the tall handsome Scotsman – and all due to the rain!

The Family of Wales

GEORGE WAS IN the schoolroom with his brother Edward. He was dreaming idly as he often did when he should be studying. He knew it was wrong; he knew he should work hard, but lessons were so tiring, and try as he might he could not grasp what his tutors were talking about. He was watching the door, hoping his father would come in, breezy and affectionate, with a new idea for a play, for George preferred acting to learning lessons. Mathematics were a bore, but history had become more interesting because his mother was constantly reminding him that he, too, would one day be a King, and this brought the aspirations of Henry VII, the villainies, in which he did not altogether believe, of Richard III, the murders of Henry VIII and the tragedy of Charles I nearer home. These men were his ancestors; he could not forget that.

But the lessons he really cared for were those of the flute and harpsichord. Edward enjoyed them, too. And their father was anxious that they should have such lessons; even that old ogre, their grandfather the King, loved music. This love was inherent, and it was said that they had brought it with them from Germany. Handel had been the very dear friend of several of his relations. George was not surprised.

Unfortunately lessons other than music had to be learned, and they were not so congenial.

‘Some persons agreed to give sixpence each to a waterman for carrying them from London to Gravesend, but with this condition: that for every other person taken in by the way threepence should be abated in their joint fare. Now the waterman took in three more than a fourth part of the number of the first passengers, in consideration of which he took of them but fivepence each. How many passengers were there at first?’

Oh dear, sighed George. This is most complicated.

Edward scowled at it and demanded to know why the future King should have to worry about such matters. Was he ever likely to travel in such a way, and if he did would he be so foolish as to make such a bargain with a waterman?

George explained painstakingly that it was not an indication that they should ever have to face such a problem in real life. It was a lesson in mathematics.

At which Edward laughed at him. ‘My dear brother, did you think I didn’t know that?’ Whereupon George’s prominent blue eyes were mildly sad and his usually pink cheeks flushed to a deep shade.

George was a simpleton, thought Edward. But at least he would work out the problem and tell Edward the answer, no matter how long it took him to do it. It was his duty to try to learn, George believed; and he would always do his duty.

George had hoped his father would come to the nursery accompanied by Lord Bute, the tall Scots nobleman who had become part of the household.

George shared the family’s enthusiasm for Lord Bute, who was always so kind and understanding to a boy such as he was. He explained everything in such a way that George never felt he was stupid not to have grasped it first time. His father was kind but sometimes impatient with him, and now and then laughed at his slowness, comparing him with Edward, who was so much brighter. It was not done unkindly, but in a bantering affectionate way; yet it disconcerted George and made him fumble more. Lord Bute seemed to understand this. He never bantered; he was affectionate and kind and… helpful. That was it. Whenever Lord Bute was near him, George felt safe.

In the family circle his father never behaved as though he were Prince of Wales; he would take his sons fishing on the banks of the Thames; and they played cricket in the Cliveden meadows. The Prince was very good at tennis and baseball, and he enjoyed playing with his own children. Lord Bute would join in the games; he was so good that he was a rival to the Prince; and the Princess Augusta would sit watching them with a little group of ladies, applauding when any of the children did well – and also applauding for the Prince and Lord Bute. George noticed that his mother applauded even more enthusiastically for Lord Bute than for the Prince of Wales.

George preferred being at Cliveden rather than Leicester House; as for those rare occasions when he was commanded to wait on the King, he dreaded them. His grandfather was an old ogre – a little red-faced man who shouted and swore at everyone and insisted on everyone’s speaking French or German because he hated England and the English, it seemed. The old man was a rogue and a tyrant. Papa and Mamma hated him, so, of course, George did too.

But even at Cliveden there were lessons to be learned, and now he must attend to this stupid affair of the waterman.

Edward was looking out of the window. Clearly he would not help. So George sighed, and after a great deal of cogitation he came up with the answer.

‘It’s thirty-six,’ he told Edward.

‘Sure?’ asked his brother.

‘I have checked it.’

Edward nodded and wrote down the answer.

George picked up the next problem but at that moment the door opened. Eagerly the boys looked up from their work; but it was not one of their parents nor Uncle Bute. It was their true uncle, the Duke of Cumberland, their father’s younger brother.

Edward was delighted by the diversion, George to see his uncle. They saw little of him, and George presumed it was because he was on the King’s side, which he concluded judiciously, was what one would expect in view of the fact that he was the King’s son.

The Duke of Cumberland was dressed for hunting – a large man inclined to corpulence, at the moment beaming with affection.

‘I was hunting in the district and thought I’d come and see my nephews.’ He embraced George first, then Edward.

Come to see his nephews! thought George. Not his brother or his sister-in-law?

‘Papa and Mamma are here,’ said George.

‘Not in the house,’ replied their uncle. ‘Doubtless in that theatre of theirs with my Lord Bute.’

George detected a certain contempt in Uncle Cumberland’s voice. He hoped Papa would not come in and quarrel with him. He hated quarrels.

‘And here are you boys sitting over your books on a sunny day like this.’

‘It’s a shame,’ agreed Edward.

‘We have to learn our lessons,’ George reminded him primly.

Uncle Cumberland pulled up a chair and sat down heavily. He laughed. ‘What do you learn, eh? What’s that?’ He picked up the waterman problem and scowled at it. ‘Much good that’ll do you.’

‘Mr Scott thinks we should be proficient in mathematics.’

‘Well, I’m not a great mathematician like Mr Scott. I’m only a soldier.’

Edward had leaned his elbows on the table and was propping up his face as he stared intently at his uncle. ‘Mathematics are a bore,’ declared Edward. ‘So are French and German.’

‘Mr Fung does his best to teach us, but we are a trial to him,’ George explained.

‘I like dancing with Mr Ruperti,’ declared Edward.

‘But music is the best of all,’ put in George. ‘It is the only subject at which we seem to make much progress. Mr Desnoyer is pleased with us.’

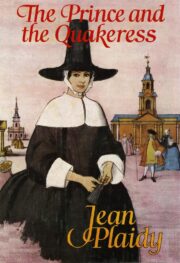

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.