Hannah liked it very well and as she smiled and chatted with Jane she was thinking: Cast out. Disowned. And when Jane had left she sat down and thought about the room over the linen-draper’s shop and all the kindness Uncle Wheeler had shown to her and her mother when they had had nowhere to go.

George found her a little melancholy.

‘You look sad,’ he said, ‘but so beautiful. I’d like to have a portrait of you just as you look now.’

She tried to throw off her melancholy but she could not and at length she confessed that she had been cast out by the Society of Friends.

George embraced her, swore eternal devotion and tried to cheer her.

But he too was a little sad, wishing as fervently as she did that they could marry and put an end to this feeling of sinfulness which was constantly between them and their happiness.

It was a comfort to be able to talk of his affairs with the brother and sister he loved dearly. Edward was only a year younger than he was, and although Elizabeth was three years his junior she had a wisdom which neither of her brothers possessed, for she had read a great deal more than they had, and although shut away from the world in common with her brothers and sisters, reading had given her some knowledge of it.

George loved Elizabeth tenderly; she aroused in him the deepest pity; she was very deformed, one shoulder being higher than the other and she limped painfully so that it was impossible for her to dance or run or even walk very much. She was good-natured and seemed to accept her disabilities philosophically, never complaining. Their mother and Lord Bute seemed scarcely aware of her existence. Poor girl, she would be at the Court for the rest of her life; there would be no marriage for her, so she would be useless as a bargaining counter; she would just be there, evidence of one of the Princess Augusta’s less successful examples of child-bearing.

She aroused all the chivalry in George’s nature. He told her: ‘You and I will be together all our lives. Perhaps it is wrong of me to be glad about that, but I can’t help it.’

Whereupon Elizabeth smiled her gentle smile and said: ‘You mean, brother, that because I’m deformed and what people kindly call “homely” I shall never be commanded to marry and leave home. I, too, rejoice that I shall never leave you. So you see good cometh out of evil.’

Now it was pleasant to tell these two of his difficulties.

‘I am a husband and yet no husband. How I wish I were truly married to Hannah!’

‘I’ll swear Hannah is very happy to have you at any price she has had to pay,’ suggested Elizabeth.

‘Shut away in that house! Never knowing when the Quakers will ride up and take her away. What an adventure,’ cried Edward.

Elizabeth smiled. ‘You speak as though Quakers were the French army, Edward. They are a mild people. They don’t believe in taking life. I have been reading about them. In fact, since George and Hannah have been together I have been reading everything I can find about them. The Society of Friends! Don’t you think that it is a pleasant way to describe themselves?’

George sat back in his chair, his eyes half closed. The next best thing to being with Hannah was to be with Elizabeth, to know that she followed every phase of his life; that she was always beside him, his very dear friend and sister who would be there until the end of his life.

‘I have been reading about George Fox who founded the Society. Oh, he was a great man – the son of a weaver in Leicestershire. “None are true believers but those who have passed from death to life by being born of God,” he said. “God does not dwell in temples made by hands, but in human hearts.” I think that is a wonderful sentiment. And it’s true.’

‘Oh yes, it’s true,’ cried George. ‘I should like to be a Quaker.’

‘That,’ retorted Edward, ‘would be quite impossible, for when you are crowned King of England you will have to swear allegiance to the Church of England – the Reformed Faith.’

‘It is not so different,’ protested George.

‘Oh, George, you must not think of it,’ said Elizabeth. ‘If you told Lord Bute or Mamma that you wished to be a Quaker they would be truly alarmed. You don’t know what they would do.’

‘What could they do?’ demanded Edward.

Elizabeth was silent. She looked at George – dearest of brothers, kindest of friends – and she was afraid. He was so good, and being simple in his goodness George was inclined to believe that everyone was as good as he was. What were they thinking now of his connection with Hannah? They deplored it, of course. If he had a mistress… two or three mistresses… about the Court, if he had behaved like a lusty young man in an immoral society where he, on account of his position could enjoy special privileges, they would have shrugged their shoulders and smiled. But George was not an immoral young man; he was a good young man who had fallen in love and believed it was for ever; he wanted his union sanctified by marriage and that was something these worldly people about him could not understand.

George needed protecting and who was she… the poor deformed ‘homely’ member of the family, of no account at all… who was she to protect the most important one of them all – George who would one day be their King.

‘They could not take me from Hannah,’ cried George. ‘I would never allow that. If they attempted to I… I would marry her and… join the Quakers.’

‘She is married already to Mr Axford,’ Elizabeth reminded him.

‘I heard,’ put in Edward, ‘that marriages conducted at those marriage mills are not considered legal.’

‘That is true now,’ agreed Elizabeth, ‘but when Hannah married Mr Axford such marriages were legal.’

‘It seems rather ridiculous,’ said George, and there was a hint of excitement in his eyes which made Elizabeth apprehensive, ‘that what is illegal now was once legal. It is the same thing, yet now it is wrong and then it was right. It seems to me that if it is wrong now it was wrong then.’

‘Hannah married Mr Axford,’ said Elizabeth, plucking at the rug which covered her knees. ‘And, George, please don’t mention to my Lord Bute that you would like to be a Quaker.’

George smiled at her blandly. ‘He would listen sympathetically. He is a wonderful friend to me… the best I have. Oh, I don’t mean better than you two… but you are my family. Well, so is he in a way. I think of him that way. But he is a statesman and a politician. I should be terrified of becoming King but for Lord Bute. But if he is there I know everything will be all right.’

‘You will soon learn to govern without relying too much on one minister,’ Elizabeth assured him.

‘All kings must have ministers,’ put in Edward. ‘Our grandfather had Sir Robert Walpole… though they say our grandmother was the real ruler… she and Walpole between them. Grandfather didn’t know that, though.’

‘Grandfather is an… objectionable old man,’ said George, remembering the blow he had received at Hampton Court. ‘I’m not surprised that Mamma and Lord Bute dislike him so much.’

‘Quarrels… quarrels,’ sighed Elizabeth. ‘I wonder why there always have to be quarrels in this family!’

‘Perhaps we are quarrelsome by nature?’ suggested Edward.

‘George, you must not quarrel with your son when you have a Prince of Wales. But of course you will not. You will be a kind King; you will put an end to this silly chain of quarrels.’

‘Well,’ George reminded them, ‘I didn’t quarrel with our Papa.’

‘There,’ Elizabeth pointed out. ‘Didn’t I say that you were far too good-natured to quarrel with anyone?’

‘Of course I was very young… too young to quarrel perhaps.’

They all laughed and were sober suddenly, thinking of poor Papa who had died so suddenly and the cruel verses that were sung about him in the streets, as though he were of no consequence.

Elizabeth was thinking that perhaps he had been of no consequence. There was still the same King on the throne; George was nearly eighteen, and at eighteen he would come of age. Eighteen was old enough to ascend the throne. And even Mamma had not been rendered exactly desolate by Papa’s death – at least after the first shock had subsided and she had begun to grasp her new power. And then, of course, there was Lord Bute to comfort her.

Our mother’s lover, thought Elizabeth, whom George so reveres because he treats him as a son. George is too trusting, he is unaware of the schemes of ambitious men.

‘Well, what are you thinking now?’ asked George.

‘How glad I am that I shall always be with you… no one is going to want to marry me. I’m glad. I shall stay at home living close to the King. I shall be your most devoted subject…’

George’s eyes filled with tears.

‘I wish,’ he said, ‘that you two could meet Hannah. You would love her and she would love you.’

‘Why do you not have her portrait painted?’

George’s eyes lightened with pleasure. ‘It’s a wonderful idea. I will do it. I will engage the best artist in England. Of course it must be done. How is it, Elizabeth, that you always know what I want before I do myself.’

‘I should set about discovering how best it can be done,’ suggested Edward.

‘And, George,’ murmured Elizabeth, ‘do remember not to mention to anyone that you would like to be a Quaker. It would never be possible… and you can never be sure what would come of it.’

‘Not even to my Lord Bute? He has asked me to tell him everything…’

She leaned forward and laying her hand on his arm looked at him earnestly.

‘Don’t mention it to anyone… but Edward and myself, George. It could be dangerous. To please me.’

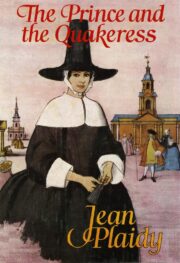

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.