‘It would be ideal, of course.’

‘Well, since the old scoundrel has his eyes on Wolfenbüttel perhaps he could be looking towards Saxe-Gotha.’

‘Our best plan would be to make George understand that he must never accept one of those girls whose mother you so dislike. Shall I sound him? Perhaps you could follow on from there.’

She pressed his hand. ‘As always you provide the answer.’

Bute found George in the schoolroom, his brow furrowed as he tried to understand the different methods of taxation which had been applied through the various preceding reigns and the measure of their success. He was very pleased to be interrupted.

‘I thought you would wish to know that the King is thinking of marrying you off.’

George turned pale. ‘It cannot be!’

‘Certainly not to the woman of the King’s choice.’

‘So he has chosen?’

Bute nodded slowly. ‘He has decided on either Sophia Caroline or Anna Amelia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. You are to pick which you prefer.’

‘I cannot marry.’

‘So your mother thinks. She has the strongest objections to either of these young females.’

‘It would not matter who they were. I consider myself married already.’

Bute nodded sympathetically. So the boy was still held in the Quaker web. But give him a little time.

‘Do not be unduly alarmed. I am sure that if you firmly decide not to be forced into marriage by your grandfather you will stay free.’

‘You will help?’

‘Have I not sworn always to do so?’

‘Oh, thank you… thank you. I don’t know what I should do without you.’

‘Why should you?’ Bute laughed breezily. ‘When you are King all you will have to do is to make me your chief minister and I shall always be at your side.’

‘Of course, that is what I intend to do.’

Oh, triumph! thought Bute. If you could hear that Newcastle…Pitt… Fox… you would shiver with apprehension. The old man cannot last much longer surely. And then this boy will be King and that means that I and the Princess will in fact rule this land. What a dazzling prospect for an ambitious man!

‘I shall keep Your Majesty to that.’ Spoken playfully to hide the sealing of a promise beneath a jocular guise.

‘Oh hush! Remember the King still lives.’

‘God save the King!’ cried Bute, and whispered: ‘And in particular His Majesty King George III.’

George smiled faintly and was immediately anxious. ‘So you understand that I could not consider marriage… any marriage. I am morally bound to Hannah. I want no one else.’

‘I understand. But have no fear. The King may attempt to force this marriage on you, but we will stand firm. He needs the consent of Parliament, and members will be afraid to give that consent, if you are firm enough. They remember that his star is setting and yours is about to rise. You must remember it, too. Do not give way easily to anything. Stand firm. Remember that any day you could become King.’

‘I do not like my grandfather. He is a disagreeable man and since he struck me I fear I can never feel what I ought towards him. But I do not care to speak of him as a dead man when he is still alive. He has as much right to live as I have… that is how I see it.’

‘A right and noble sentiment worthy of Your Maj… Your Highness. But I am warning you. Stand firm. Declare your refusal to take one of these girls and your grandfather is powerless.’

‘How can I thank you!’

‘Oh,’ laughed Bute. ‘Don’t forget the promises you have made to me.’

‘I swear I never will.’

Bute was able to tell the Princess that he had persuaded the Prince to stand out against the Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel proposition.

‘We have nothing to fear from St James’s Palace. The King will see that he cannot rule the Prince from there. We are his guardians – and we must see that it remains so.’

The King’s face was purple with rage.

‘So the puppy won’t be bewolfenbüttled, he says. I’ll teach him whether to defy me. I say he shall be bewolfenbüttled, and like it. I’ll have him yelping to me to hurry on the marriage, I promise you, Waldegrave. He doesn’t want to marry? Well, it is his duty to marry, and I am going to see he does his duty.’

‘Your Majesty, the Prince would have some support in Parliament.’

‘Support! What support?’

‘He is the Prince and he has his following. His mother’s friends would be ready to uphold him.’

‘Who is she? Fred’s widow. I am the King of this country and I’ll be obeyed.’

This was a difficult task, Waldegrave realized; and he secretly thought that the sooner he was released from his position of tutor to the Prince of Wales and chief King’s spy in the Princess’s household the better.

‘If a vote were taken on the matter of the Prince’s marriage the result might well be in his favour.’

‘But I say he shall marry the girl. He’s no longer a boy. He’s proved that, hasn’t he? Sniffing round Markets! If his grandmother were alive. Ah, there was a woman…’

Waldegrave allowed his mind to wander for five minutes. The King must be made to see that he could not force the Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel marriage just yet. The Prince was only seventeen. It was another year before he would officially come of age. The old King was well over seventy; everyone had expected him to die at least ten years ago. He could not last much longer; in fact, when he went into one of his frequent rages they expected him to have an apoplectic fit on the spot. With the purple colour in his cheeks, his prominent eyes bulging and veins knotting at his temples he really looked as though he were on the verge of a stroke. And there was young George, seventeen years old, with his fresh pink skin and his blue eyes almost as prominent as his grandfather’s but placid, and the same heavy jaw, though in his case, sometimes sullen, where the King’s was more likely to be bellicose.

How could Waldegrave explain to the King that ambitious ministers would be more likely to support the young man who must certainly ascend the throne in a few years time rather than an old one who must most certainly soon leave it.

But perhaps the King saw that, for when he had finished the five minute eulogy on the dead Queen, he said: ‘I heard a rumour that that woman has her eyes on Saxe-Gotha. I tell you this Waldegrave, there’ll be no Saxe-Gotha woman for my grandson. I’ll not have our family tainted by that lot. And I’ll tell you this too, Waldegrave: there’s madness there. I shall stand firmly against any of her plots in that direction. No Saxe-Gotha here. Do you understand?’

Waldegrave replied that he understood His Majesty perfectly.

No Saxe-Gotha! And no Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel either.

The marriage of the Prince of Wales was satisfactorily shelved for a while.

The King was alarmed. Foreign affairs were at a very low ebb. England’s place in the world was insignificant. There was one man who railed against this with a passionate fury so intense that it had impressed the King. He thought a great deal about William Pitt. There was a man who impressed him deeply. Pitt was a man of words – the finest orator of his day. He could turn a phrase and bring tears to the eyes; he could present an argument and convince.

When he had been young and lusty the King had preferred to live in Hanover rather than England; but when he had been a still younger man he had professed a great love for England but that was only because his father had hated it and he automatically loved all that his father hated. In the days when he had first come to England with Caroline he used to say: ‘If you vould vin my favour call me an Englishman.’ He had always spoken in English then – with a marked German accent, of course – but that was because his father George I had refused to learn a word of the language. But when he became King he felt it undignified to speak a language which his subjects spoke so much better, and everyone about him had to speak in French or German. Then, of course, he had made several attempts to sacrifice England to Hanover which Sir Robert Walpole had prevented.

But that was the past. He was an old man – he was a vain old man – and no King, particularly one who has always made a semblance of virtue, wanted to leave his country in a worse state than that in which he found it.

‘If Valpole vere here,’ he mused, lapsing into English. ‘If my dear Caroline vere here…’

Those days were past and Newcastle was no Walpole. But there was Pitt.

He thought of Pitt. The orator, the man of war, who deplored the desultory state of Britain’s arms. Pitt had grandiose schemes. He talked of Empire – and by God, how he talked! No one could talk like Mr Pitt. He could make people see a country astride the world, leading the world, in wealth, in commerce. That was Mr Pitt’s dream of England, and he wanted a chance to make it become a reality.

He was called a war-monger. Such men always were. Did any man think that great rewards could be gained without effort. If so, that man was a fool.

The King decided to send for Mr Pitt.

In the presence of such a man even a King must feel insignificant. George usually hated to feel insignificant; that was why he never liked tall men. But this was different. George was not thinking so much of the King of England as of England itself. Some instinct told him that Mr Pitt was the man; and if he were tall of stature, imposing in personality, on this occasion, so much the better.

His manner was deferential – almost servile – another quality which pleased the King. There was nothing arrogant about this man in the presence of royalty, although he could be haughty enough with those whom he considered beneath him. He was vain in the extreme; he held himself erect; he had a little head, thin face and long aquiline nose, heavy lidded eyes… hawk’s eyes. He was like an actor on a stage, thought the King; he might have stepped right out of a play; and when he spoke it might have been Garrick or Quin speaking; the beautiful cadences of his magnificent voice filled the apartment and demanded respect.

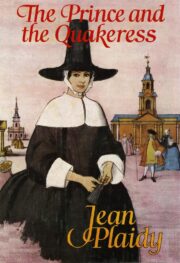

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.