‘How can I know what will happen when I get to this house?’

‘You have seen the gentleman. You could trust him.’

Yes, thought Hannah. I have seen him – an innocent young boy. Of course she could trust him. He was no lecherous roué out for a new sensation with a prudish Quaker girl. She knew she could trust him. So since he so desired to see her, she must go to him.

‘I will come,’ she said.

Jane was jubilant. She could scarcely wait to call on Mr Jack Ems to tell him that the first step had been taken.

George left the Palace for the Haymarket where Miss Chudleigh had engaged a suite of rooms for him. As his chair was carried to its destination no one glanced at him as he was travelling incognito, just an ordinary gentleman with his private chair, his chairmen and his footman.

He was very excited. He had been daring. It was the first time he had acted without the approval of his mother or Lord Bute, and he did wonder very much what they would say if they knew what he was doing. Miss Chudleigh had warned him not to betray his actions, for his mother and Lord Bute would surely try to stop him if he did.

‘I should not really go against their wishes,’ said George. ‘Everything they do is for my own good.’

‘And for their own,’ retorted Miss Chudleigh.

‘But mine is the same as theirs,’ replied George.

How well they have trained their little tame pet, thought Miss Chudleigh. Well, there were going to be some surprises in Court circles when it was discovered that little George had suddenly become a man.

‘Everything,’ Miss Chudleigh said quickly, ‘will depend on Miss Lightfoot.’

‘Oh yes, everything must depend on her.’

George’s heart was beating wildly as he opened the door of the suite. A man was waiting to bow him into a room which was pleasantly though not luxuriously furnished. With him was a young woman, obviously Hannah’s servant.

‘My lord, the young lady will stay for half an hour and then she must be gone.’

‘It… it shall be as she desires,’ stammered George.

‘If your lordship will excuse me… the lady will be here immediately.’

For a few seconds George was alone in the room; his throat constricted, his sight blurred. Nothing like this had. ever happened to him before; it was like something he had dreamed. And it was all due to clever Miss Chudleigh.

The door opened and she stood there – the beautiful vision from the linen-draper’s window. He gasped and she came towards him, serene – she would always be serene – and only the faint colour in her cheeks betraying the fact that she was excited.

‘I… I trust you are not displeased,’ he stammered.

She curtsied. ‘Your Highness must forgive me. I have never been taught how to behave with royalty.’

What simply charming words! How graciously spoken.

Some impulse made him kneel before her.

‘Oh no,’ she said. ‘Thou must not.’

Thou must not. What a delightful manner of expression. It suited her. He wanted to kiss her hand, but he felt that he should not touch her yet. She might object and he did not want her to go away before he had had a chance to speak to her.

He rose to his feet rather clumsily. ‘You are more beautiful close than in the window.’

‘Your Highness is very kind to me.’

‘I want to be. I wish I knew how.’

‘Shall we sit down and talk?’

Everything she said seemed to him so wonderful, so wise.

They sat side by side on a sofa; he was careful not to sit too close for fear she should object. ‘I have never talked much to ladies,’ he said.

She was moved by his sincerity and honesty. Nothing could have charmed her more. He was incapable of pretence; he was charmingly innocent. And he was the Prince of Wales!

She said: ‘I know thou art the Prince of Wales.’

‘I hope that does not displease you.’

‘No, but it makes it difficult for us to be friends.’

He was alarmed. ‘I feared so. But Miss… er… a friend of mine has told me that it is possible for us to meet.’

‘As we have now.’

‘I hope that this will be the first of many meetings.’

‘Is that what thou wishest?’

‘I wish for it more than anything on earth. I have never seen anyone as beautiful as you are. I would be happy if I could look at you for the rest of my life.’

She smiled gently. She was almost as inexperienced of life as he was; and it was pleasant to sit beside him and talk.

She talked more than he did for he was so fearful of offending her. She told him of how she had come to the linen-draper’s shop and of her life there. He listened avidly as though it was a tale of great adventure. They could not believe that the half-hour was over when Mr Ems scratched discreetly on the door.

George seized her hands; he could not leave her without her assurance that they would meet here again… within the next few days.

If it could be arranged, Hannah said, she would be there.

Jane looked at her curiously as they jolted back to Jermyn Street in their closed carriage. She seemed more excited than Hannah; but Hannah had changed; there was a quiet radiance about her. She knew she was loved, devotedly and unselfishly by no less a person than the Prince of Wales.

The Elopement

THE MEETINGS WERE taking place regularly. The closed carriage, the journey with Jane, the ecstatic reunion in the Haymarket… they had become a pattern of life. George loved her. He had said so. He admitted he knew little of life, but one did not have to learn about love; it came to one and there it was the meaning of one’s existence.

They talked of love; of their adoration of each other; it was enough to be sure of their meetings, to touch hands and occasionally kiss. Each was aware of the barriers which separated the niece of a linen-draper and a Prince of Wales; but they did not discuss this matter.

All they asked was to be together.

Hannah had changed. She did not realize how much. When one of the children spoke to her she was absent-minded; she forgot to perform those household tasks which had been second nature to her; moreover, her beauty had become so dazzling that even the linen-draper noticed.

‘What is happening to Hannah?’ he asked his wife.

Lydia and Mary had been aware of the change before he had, and Lydia replied that she wondered whether Hannah was in love.

‘She goes often to Ludgate Hill,’ went on Lydia. ‘I suspect that she goes to see Isaac. Perhaps it is time to arrange a marriage.’

‘Isaac is younger than she is and scarcely in a position to marry.’

‘Perhaps if she had a fair dowry…’

‘We have our own daughters to think of. Hannah has beauty. Perhaps that should be considered dowry enough.’

‘Well, she is twenty-three years of age and that does seem old enough for marriage. It is our duty to see her settled even as our own daughters.’

Henry agreed that this was so and that although Isaac was young and it would be many years before he inherited his father’s business, the Axfords were a good Quaker family and Hannah must of course marry into the Society of Friends.

Henry decided to walk over to Ludgate Hill to have a word with Mr Axford about his son and Hannah. He talked to Mr Axford who said that Isaac was somewhat young for marriage but that he was no doubt taken with Hannah and as she was a good Quaker he would have no objection to the match. A dowry would be helpful. Grocery was not so profitable as linen-drapering, and Isaac would need to put a little money into the business.

Mr Wheeler explained that he was not in a position to put up a large dowry for a girl who was after all only his niece when he had daughters of his own to think of. But the young couple were clearly attracted. Hannah was constantly making excuses to call at the grocer’s.

‘She comes here rarely,’ said Mr Axford. ‘Only to order the grocery, and then she is in and out in no time.’

Mr Wheeler replied that he had been mistaken in that and doubtless Hannah spent the time at the glass-cutter’s with her friend Jane.

But he was disturbed.

A few days later he was more than disturbed; he was alarmed. He had followed Hannah and Jane and seen them get into the closed carriage; he had gone into a coffee house and sat watching the house in the Haymarket. He had seen Jane and Hannah emerge and get into the carriage; he had waited in the coffee house and seen a young man, little more than a boy, come out of the house. He knew that face. He had seen it many times.

It could not be. It was impossible. But such things had happened before. The closed carriage; the secrecy. Only someone in a high place would make such arrangements. In a high place indeed!

Here was… disaster. Here was scandal. His niece Hannah was clandestinely meeting the Prince of Wales. For what purpose did Princes make assignations with humble girls?

This was disgrace such as had never befallen the Wheeler family before. Death was preferable to dishonour, and Hannah was bringing dishonour to their household. A Quaker girl a Prince’s mistress. Something must be done at once.

But what? Mr Wheeler was a shrewd and cautious man. There was no sense in shouting their disgrace to the housetops. If he did, Hannah’s conduct would bring disrepute to the entire community of Quakers. It was never comfortable to be members of a minority religious group. Such groups were always open to persecution. The essence of the Society of Friends was simplicity, chastity, devotion to duty; and when their members strayed from virtue, when a Quaker girl became a harlot, that was a far greater crime than when a woman who was not a Quaker behaved in such a way.

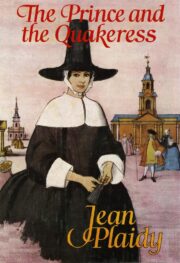

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.