How strange! thought Hannah. What could it mean? She thought him charming, beautiful in his innocence. He was like a child – untouched by the world, perhaps as she was. She must be many years older than he was – six, seven, eight even – but there was a bond between them, a bond of unworldliness. They were like two children looking at life through a glass door, aware of it, yet ignorant of it. She had been warned of lascivious men; in fact their glances had often come her way. Her uncle could not protect her from that; she was so attractive and he could not shut her up in a lonely tower until he found a Quaker husband for her.

This was different. This was the pure adoration of an innocent boy, years her junior – and he was a Prince. More than that, one day he would be a King.

It was small wonder that she was bewildered.

When Jane married and went to live in Cockspur Street with her husband, Hannah was desolate. As Mr H. was still an apprentice the only way in which Jane could join him in his master’s house was by going into service there. Thus she left her employment in the Wheeler house to join that of Mr Betts, the glass-cutter of Cockspur Street.

They did not need another servant, decided Mr Wheeler. Rebecca was old enough to perform small duties about the house and it was good for her to be useful; George could do minor errands for the shop; there were three able-bodied women in the house, Lydia his wife, Mary his sister and Hannah his niece. Therefore what did he want with serving-maids?

So there was no one now for Hannah to chat to in that frivolous but enjoyable way. She heard, of course, that the Prince of Wales had died; and that brought home to her the astounding fact that the young boy with whom she believed she had a secret understanding was now the Prince of Wales. That made the affair so fantastic that she began to believe she had imagined the whole thing. The Prince seemed to have ceased his visits to the Market and life had become very drab indeed. Her days were lightened only by her shopping expeditions to Ludgate where she sometimes lingered in the grocery shop talking to the grocer’s son, Isaac Axford. The Axfords were Quakers like themselves; so naturally they did business together. Isaac was half in love with her, she believed; he was three years younger than she was and not in a position to marry, but she had no wish to marry him. There had been a time when she supposed a marriage would be arranged for her by her uncle, and Isaac had seemed a likely partner; after all, being only the niece of the prosperous linen draper, she could not expect a dowry as enticing as that he would give to his own daughters.

Hannah thought of married life in the grocer’s shop at Ludgate Hill and it did not attract her. She liked Isaac but only mildly. Yet, but for the penetrating glances of a young boy she might have been contented enough to accept him.

Jane came visiting from Cockspur Street and the two young women sat in Hannah’s room and looked over the Marketplace, together.

Married life was a disappointment, Jane admitted. She was no better off than she had been on her own. Mrs Betts was a good-natured mistress, easy-going and not unfriendly, but there was little money.

And living in the heart of London, seeing the fine ladies and gentlemen in their carriages and chairs, going to balls and banquets and the theatre did make a young woman discontented with her lot, particularly when she was prettier than some of those painted, bedecked creatures in their silks and brocades and glittering gems.

Jane tossed her pert pretty head and said she was a fool to have rushed into marriage. She fancied she could have had other opportunities and she feared Mr H. would never be anything but an apprentice, for he had no money to set himself up in business.

And what of Hannah – Hannah who was beautiful? Was she going to spend her days dressed in a Quaker bonnet and gown, never having a chance to display her charms?

Hannah smiled at Jane’s petulance. It was good to be able to chat with her friend again.

Journey in a Closed Carriage

THE DOWAGER PRINCESS of Wales was where she liked to be best in the world; in the company of her dear Lord Bute.

So handsome! So clever! What should she do without him? Now even more than ever, for she was by no means old, and since poor Fred was dead there was nothing to keep them apart.

Her lover and her children – they were her life.

‘Dearest John,’ she was saying, ‘I was just asking myself what I should do without you.’

‘What a monstrous thought. Why should you?’

‘Because we are always fearful of losing what we most value.’

‘If you lose me it will be of your own choosing, for it will never be mine.’

‘Ah, dearest John. What happiness you give me! Is there much scandal about us, do you think?’

‘Whatever we did there would be scandal, so…’

‘We may as well earn it?’

They laughed and embraced.

‘The old man could scarcely complain of us,’ she said.

‘His Majesty complains of everyone, so what would it matter if he did?’

‘At his age! You would think he were past such adventures.’

‘Perhaps he is, and won’t admit it.’

‘I remember when my mother-in-law was alive, how he used to write to her about Walmoden from Hanover. How should he proceed with the seduction? And his father with those two grotesque women of his – one tall and thin, the other short and fat. They were a laughing-stock. John… I am afraid for George. I am afraid he will take after them and if he gets a fondness for women…’

‘It will be natural enough. He’ll soon be thinking of taking a mistress, I’ll swear.’

‘But George is different. He is not like his father, his grandfather or his great-grandfather. Frederick… well, you knew Frederick as well as I; and George I always had his women, plenty of them. Our present King has always been chasing them, even when in fact he preferred his wife he felt it necessary to his dignity as a King to have his mistresses. George I was a dour man and people were afraid of him – even his women. George II is irascible and a silly little man easily deceived, but his women fear to offend him. George III will be different.’

‘There is an innocence about him,’ admitted Bute.

‘Yes, I fear what would happen to him in the hands of some scheming woman.’

‘He is a boy yet.’

‘Fifteen! His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were already experimenting in sexual adventure at that age.’

‘But not our George.’

‘No, not our George. He is an innocent boy. I want to keep him so. I want to make sure that he does not mix with people of his own age at the Court. The young are especially dissolute nowadays. I want to keep George and his brothers and sisters innocent.’

‘For a while, but they must learn something of the world. Although as you say, they are young yet.’

‘I do not care for the behaviour of some of your young people.’

‘We will keep our eyes on him,’ said Bute, ‘together…’

‘Together,’ she murmured smiling at him.

Bute had left her. Augusta yawned contentedly. There was no one in the world like him, no one whom she could trust to help her with the bringing up of her family – and particularly George.

Dear George. Poor George. She thought almost as much of him as she did of dear Lord Bute. Nobody was going to take her son from her. She was going to guide him and make sure that he was protected from the world.

One of her women had come into the apartment. It was Elizabeth Chudleigh, a handsome girl but one who had, according to rumours, lived rather more recklessly than a young unmarried woman should. Elizabeth was not so young, being round about thirty. She was gay and amusing, and at one time everyone had thought she would make a brilliant marriage with the Duke of Hamilton. That had gone wrong, however. Why, Augusta was not sure; but of one thing she was sure, and that was that Elizabeth Chudleigh was a very experienced young woman indeed.

‘Elizabeth,’ she called.

Elizabeth came and stood before her. ‘Your Highness wishes for something?’

‘I feel, Elizabeth, that I should warn you. There are some unpleasant rumours going about the Court concerning you.’

‘Oh, Madam, I have heard it said that a woman should only worry when there are no rumours about her. Then it means that the world has lost interest in her.’

‘Rumours are not becoming when attached to a young unmarried woman.’

‘Do they say of me that I have another lover?’

‘I hope, Elizabeth, that that is not true.’

Elizabeth lowered her eyes and looked very demure.

‘Ah, Your Royal Highness knows chacun à son But.’

The Princess was astonished. She could find no words. Elizabeth said: ‘Did Your Highness wish me to perform some task?’

‘No, no,’ said Augusta shortly, ‘you may leave me.’

Now, thought Elizabeth, that is the end of me. And all for the sake of a bon mot. It was pretty good, though. I would never have dared if it had not been so good. Did she get the But? Or did she think I was merely quoting the French proverb? However, she was too flabbergasted to reply… just then. But that does not mean there will not be some riposte. And when it comes… Goodbye to Court, Elizabeth.

To hell with the Court! And what would happen if she were dismissed? She should have thought of that before she allowed her tongue to run away with her. She was a fool at times. Hadn’t she allowed herself to be carried away by her feelings before? If she had not been so foolish as to believe Hamilton had deserted her, if she had tried to find out why he did not write, she would have discovered the perfidy of Aunt Hanmer and waited for him. Instead she had allowed herself to be carried away by pique and had made the mésalliance with John Hervey. Thank Heaven she had kept it secret, even the birth of their child who, alas, had died when she had put him out to nurse. If Madam Augusta knew the dark secrets of her lady-in-waiting she would have been dismissed from Court long ere this. That secret she believed was well guarded and the King was pleased enough with her to have made her mother housekeeper at Windsor – a pretty profit in that; and he had helped them to acquire a farm of a hundred and twenty acres. So she had not done too badly at Court and if Augusta should decide to dismiss her no doubt there would be a place for her in the King’s Court.

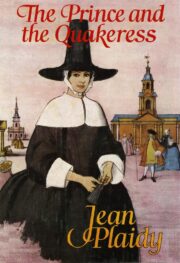

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.