His mother might rage about the fiends who wanted to take her son from her; he would always answer her mechanically. Even when Lord Bute spoke to him he scarcely heard. His thoughts would be occupied by the beautiful young woman in the linen-draper’s shop.

The Quakeress of St James’s Market

HANNAH LIGHTFOOT HAD been about five years old when she and her mother had come to live with Uncle Henry Wheeler in St James’s Market. Memories of life before that were vague, something to dream of with horror, to awake from shuddering in the comfortable bed in the room she shared with her mother, for her father’s shoemaker’s shop in Wapping had been very different from Uncle Henry’s prosperous establishment in St James’s Market.

She could not remember her father; perhaps life had been easier when he was alive; she had been two when he died. Her mother told her of how her family – the Wheelers, always spoken of with awe – had not been very pleased with the marriage. Matthew Lightfoot had not been a good Quaker and it had been against the advice of her family that she had married him; they were not surprised that she had lived so poorly in Wapping.

But Matthew had died and Uncle Henry being a deeply religious man and a Quaker had, after giving his sister Mary three years in which to struggle on in expiation of her folly, come to her rescue and offered her a home in his linen-draper’s establishment.

So as a child Hannah would lie in the big bed beside her mother and listen to the sounds outside the shop which never failed to delight her – the voices raised in bargaining, the lowing of cattle brought to the market for sale; the grunting of pigs, the reedy voice of the ballad singer; the shouts of the pieman; the street traders’ songs.

‘Won’t you buy my sweet blooming lavender

Sixteen branches one penny . . .’

Or:

‘Three rows a penny pins,

Short whites and middilings.’

She would sing the songs to herself – quietly because singing was frivolous – as she dressed in the warm sun of summer or the cold of winter, for it was bitterly cold in winter. It was not that Uncle Henry could not have afforded a fire; but he believed in the Spartan life. In spite of prosperity they must live simply.

In the bad dreams – which grew less as the years passed – she would hear the scrape of a boat against the stairs; she would smell the slimy, tarry smell of the river; she would hear men whistling tunes or singing river songs, shouts of abuse, the voices of men and women raised in anger as they fought each other. She would remember the vague empty feeling which was hunger; the numbness which was cold – not the healthy cold of Uncle Henry’s house but the cold which came of insufficient covering, insufficient food. They had stepped over a bridge it seemed to Hannah from hunger and poverty and want to the well-being which came from righteous living – thrift and piety. Uncle Henry was like a beneficent god – a knight of old who had rescued them from dragons, and carried them away from the dungeons of despair into the castle of comfort.

Her mother shared her pleasure, she knew. Mary Lightfoot could not do enough for her brother.

Uncle Henry had been a bachelor of thirty-one when Mary and her daughter came to live with him. Mary therefore could be of use to him, for she was an excellent housekeeper and she began to transform his house into a home as no servant could do. Henry was fond of his niece, for she was a charming girl and indeed grew prettier every day. Not that as a Quaker he believed in stressing those charms. The dark curls should be severely strained back from the oval face and neatly braided. The child should be attired in a simple gown of grey cloth.

‘Clothes are meant to keep the child warm, sister,’ said Uncle Henry, ‘not to adorn her.’

‘Oh yes, brother,’ Mary agreed fervently.

But as Hannah grew a little older she found a great pleasure in beautiful things and when one of the flower-sellers in the market gave her a rose she carried it up to her room and pinned it on her dress. Her great dark eyes seemed to glow more brightly; the pink of the flower toned perfectly with the grey cloth and seemed to bring out the delicate pink in Hannah’s own clear skin.

Uncle Henry cried out in dismay when she came down to dinner wearing the rose.

‘What is that thou art wearing, Hannah?’ he asked, and she thought that the devil must have changed the beautiful flower into a toad or something horrible since that was the only way she could account for Uncle Henry’s horror.

She looked down at it. ‘It… it is a rose… Uncle.’

‘A rose. And what is it doing there?’

‘It is just there… Uncle.’

‘How didst thou come by such a thing?’

She was bewildered. She had been so pleased to be given the rose; she enjoyed its scent; and the contrast of colour it made on her dress; she had felt happy wearing it. And now it seemed she had done a dreadful thing.

‘Old Sally the flower-seller gave it to me.’

‘Thou shouldst not have taken it.’

‘She wished it, Uncle.’

‘The place for flowers is in gardens. God put them there. He did not mean them to be worn for vanity.’

She had flushed and although she was unaware of this, her beauty was startling. It alarmed Uncle Henry as well as her mother. They would have preferred to see her insignificant.

‘Thou art guilty of vanity, niece,’ said Uncle Henry. ‘I think thy mother will agree with me.’

‘Indeed yes, Henry,’ whispered Mary Lightfoot.

‘This is a sin in the eyes of the Lord. Thou wilt go to thy room. Take off that flower. Give it to me… now…’

She felt the tears in her eyes. For a few seconds she hesitated, almost ready to defy him. Then she was aware of her mother’s terror; and she pictured them being turned out of this comfortable house… back to Wapping… the cold, cold room, the smell of boots and shoes… the smell of the river and the vague lightness of hunger. Then with trembling fingers she handed him the rose.

He took it and said to her in a voice that thundered with indignation so that she was reminded of Moses returning from the mountain to find his people worshipping the golden calf: ‘Go to thy room. Pray… pray long and sincerely for God’s help. Thou hast need of it.’

She walked slowly up the stairs. The feeling of sin weighing heavily on her.

In the cold room she knelt and prayed until her knees were sore. Then her mother came in and they prayed together.

When they rose from their knees and Hannah’s mother appeared to think she had gained God’s forgiveness for her wickedness, she ventured to say as though excusing herself: ‘But it was such a pretty rose.’

That gave Mary an opening for one of those lectures which were so much a part of Hannah’s upbringing.

‘Sin often comes in the guise of beauty. That is why it is so easy to fall into temptation.’

When she was alone Hannah would stand at the window and watch the ladies and gentlemen pass through the market on the way to the theatre. They were so beautiful but so sinful, for they wore more adornments than a single rose. Hannah feared it was probably sinful to watch such people. There was so much sin in the world that it seemed one must constantly be on the alert for it. There they were, the ladies in their Sedan chairs, and surely their complexions could not have been naturally so brilliant as they appeared; ornaments flashing in their hair; feathers, diamonds… What a load of sin they must carry on their persons if a simple rose could be so full of iniquity.

But how Hannah loved to watch them! Gentlemen with brocade coats and elegant wigs; footmen running ahead of their chairs to clear the way and while some in the crowd gaped at their magnificence others were too accustomed to the sight to pay much attention, unless it was a person of some note. Then the crowd would cheer or boo, however the mood took them; but they would almost always laugh. There seemed to be such a lot that was gay, amusing, interesting and such fun going on down there. Fun? It was sin. But Hannah was conscious of a quiet rebellion within her. If one sinned in ignorance could one be blamed? She thought not – at least it could not be quite so wicked to sin in ignorance. Therefore how much better it was to remain in ignorance.

She would tell no one of the pleasure she derived from looking down on the noisy excitement of St James’s Market.

Hannah was ten years old when Uncle Henry decided to marry. What consternation there was in the room she shared with her mother. Mary Lightfoot feared the cosy existence might be at an end. Henry was good to them; but what of Henry’s wife?

Five years of living comfortably – at least as comfortably as one could live in such close proximity with sin – had softened them. Mary was disturbed – not that she believed her brother would see her go hungry, he was too good a man for that; but a strange woman in the house would be sure to change something and Mary trembled for the future.

She need not have feared. Aunt Lydia proved a meek and docile wife – a true Quaker, a virtuous woman who would no more have thought of turning out her sister-in-law and her fatherless child than she would of taking a lover.

After the first mild difficulties of settling down Mary and Hannah adjusted themselves to the new régime. Uncle Henry was the head of the house – good but stern, anxious to care for those under his roof – his sister and her child, no less than his wife and his own children. The children began to arrive in due course; George three years after the wedding, Rebecca two years later, Henry two years after that and Hannah two years after Henry. Mary and her daughter Hannah soon found new ways of being useful in the house and Mary realized that their position was yearly becoming more secure. Hannah was nurse to the children; Mary helped her sister-in-law in the house. It proved to be a very satisfactory arrangement.

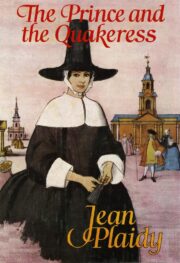

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.