‘It was his duty,’ said Louis. ‘Had he been my subject he would have worked so for me.’

There was nothing Henry could do now to prevent the case of Thomas Becket being put before the Pope, and he made sure that his side of the case should be well represented; that old enemy of Thomas’s, Roger, Archbishop of York, was among his emissaries.

The friends Thomas could send, headed by Herbert, were humble in comparison; they had no rich gifts to bring to the Pope. The Pope in his Papal Court at Sens received them with affection however and was deeply moved when he heard of the suffering of Thomas Becket.

‘He is alive still,’ he said. ‘Then I rejoice. He can still, while in the flesh, claim the privilege of martyrdom.’

The next day the Pope called a meeting and the King’s embassy and those who came from Thomas were present.

Carefully the Pope listened to both sides of the story and later sent for Thomas.

When he was received by the Pope and his cardinals, Thomas showed them the constitutions he had brought from Clarendon. The Pope read them with horror and Thomas confessed his sin in that he had promised to obey the King and that only when he had been called to make the promise in public had he realised that the King had no intention of keeping his word. After that he had determined to stand out against Henry no matter what happened.

‘Your fault was great,’ said the Pope, ‘but you have done your best to atone for it. You have fallen from grace, but my son, you have risen stronger than you were before. I will not give you a penance. You have already expiated your sin in all that you have suffered.’

Thomas was determined that they should know the complete truth.

‘Much evil has fallen on the Church on my account,’ he said. ‘I was thrust into my post by the King’s favour, by the design of men, not God. I give into your hands, Holy Father, the burden which I no longer have the strength to bear.’

He tried to put the archiepiscopal ring into the Pope’s hands, but the Pope would not take it.

‘Your work for the Holy Church has atoned for all that has happened to you,’ he said. ‘You will receive the See of Canterbury fresh from my hands. Rest assured that we here shall maintain you in your cause because it is the Church’s cause. You should retire, my son, to some refuge where you can meditate and regain your strength. I will send you to a monastery where you must learn to subdue the flesh. You have lived in great comfort and luxury and I wish you to learn to live with privation and poverty.’

Thomas declared his burning desire to do so and it was arranged that he should for a while live at the Cistercian monastery of Pontigny which was in Burgundy.

Eleanor was once more pregnant and a few days after Christmas in the year 1166 another son was born to her. They called him John.

Soon after the birth of this son Eleanor began to wonder why the King’s visits to Woodstock always raised his spirits. There was a lilt in his voice when he mentioned the place.

What, she asked herself, was so special about Woodstock? A pleasant enough place it was true, but the King had many pleasant castles and palaces. She determined to find out.

When Henry was at Woodstock she joined him there and she noticed that he disappeared for long spells at a time, and that when she asked any of her servants where he might be, she could get no satisfactory answer.

She decided she would watch him very closely herself and all the time they were at Woodstock she did this. One afternoon she was rewarded for her diligence. Looking from her window she saw the King emerging from the palace, and hastening from her room she left by a door other than the one which he had used, and so before he had gone very far she came face to face with him.

‘A pleasant day,’ she said, ‘on which to take a walk.’

‘Oh yes, indeed,’ he answered somewhat shiftily she thought, and was about to say that she would accompany him when she noticed attached to his spur a ball of silk.

She was about to ask him how he had come by this when she changed her mind.

She said that she was going into the palace and would see him later. He seemed relieved and kissed her hand and as she passed him facing towards the palace she contrived to bend swiftly and pick up the ball of silk.

He passed on and she saw to her amazement that a piece of the silk was still caught in his spur and that the ball unravelled as he went.

She was very amused because if she could follow the King at some distance she would know exactly which turn he had taken in the maze of trees by following the thread.

It was an amusing incident and if he discovered her they would laugh about her shadowing him through the maze of trees.

Then it suddenly occurred to her. He had been visiting someone earlier. It must be a woman. From whom else should he have picked up a ball of silk.

A sudden anger filled her. Another light of love. He should not have them so near the royal palaces. She would tell him so if she discovered who his new mistress was.

He was deep in the thicket, and still he was going purposefully on. She realised suddenly that the end attached to his spur had come off and he was no longer leading her. Carefully she let the end of her silk fall to the ground and followed the trail it had left. There was no sign of Henry.

She would leave the silk where it lay and retrace her steps to the Palace. When the opportunity arose she would explore the maze and see if she could discover where Henry had gone.

She was very thoughtful when he returned to the palace for there was about him a look of contentment which she had noticed before.

The next day Henry was called away to Westminster and she declared her intention of staying behind at Woodstock for a while. Immediately she decided to explore the maze. This she did and found that the thread of silk was still there. She followed it through the paths so that she knew she was going the way the King had gone. Then the silk stopped but she could see that the trees were thinning.

It did not take her long to find the dwelling-house.

It was beautiful - a miniature palace. In the garden sat a woman; she was embroidering and in a little basket beside her lay balls of silk of the same size and colour as that which had attached itself to the King’s spur.

Two young boys were playing a ball game on the grass and every now and then the woman would look at them.

There was something about the appearance of those boys which made Eleanor tremble with anger.

The woman suddenly seemed to be aware that she was watched for she looked up and encountered the intent eyes of the Queen fixed on her. She rose to her feet. Her embroidery fell to the floor. The two boys stopped playing and watched.

Eleanor went to the woman and said:

‘Who are you?’

The woman answered: ‘Should I not ask that of you who come to my house?’

‘Ask if you will. I am the Queen.’

The woman turned pale. She stepped back a pace or two and glanced furtively to right and left as if looking for a way of escape.

Eleanor took her by the arm. ‘You had better tell me,’ she said.

‘I am Rosamund Clifford.’

The elder of the boys came up and said in a high-pitched voice: ‘Don’t hurt my mother, please.’

‘You are the King’s mistress,’ said Eleanor.

Rosamund answered, ‘Please … not before the children.’ Then she turned to the boys and said: ‘Go into the house.’

‘Mother, we cannot leave you with this woman.’

Eleanor burst out laughing. ‘I am your Queen. You must obey me. Go into the house. I have something to say to your mother.’

‘Yes, go,’ said Rosamund.

They went and the two women faced each other.

‘How long has it been going on?’ demanded Eleanor.

‘For … for some time.’

‘And both of those boys are his?’

Rosamund nodded.

‘I will kill him,’ said Eleanor. ‘I will kill you both. So it was to see you … and it has been going on for years, and that is why he comes so much to Woodstock.’ She took Rosamund by the shoulders and shook her. ‘You insignificant creature. What does he see in you? Is it simply that you do his bidding? You would never say no to him, never disagree, never be anything but what he wanted!’ She continued to shake Rosamund. ‘You little fool. How long do you think it will last …’

She stopped. It had lasted for years. There might be other women but he kept Rosamund. He would not have kept Eleanor if it had not been necessary for him to do so. She was jealous; she was furiously jealous of this pink and white beauty, mild as milk and sweet as honey.

‘Do not think that I shall allow this to go on,’ she said.

‘The King wills it,’ answered Rosamund with a show of spirit.

‘And I will that it should end.’

‘I have told him that it should never have been …’

‘And yet when he comes here you receive him warmly. You cannot wait to take him to your bed. I know your kind. Do not think you deceive me. And he has got two boys on you has he not! And promised you all kinds of honours for them I’ll swear! You shall say goodbye to him for you will not see him more, I promise you.’

‘You have spoken to the King?’

‘Not yet. He knows not that I have discovered you. He is careful to hide you here, is he not? Why? Because he is afraid his wife will discover you.’

‘He thought it wiser for me to remain in seclusion …’

‘I’ll warrant he did. But I found you. One of your silly little balls of silk led me here. But I have found you now … and this will be the end, I tell you. I’ll not allow it. And what will become, of you, think you, when the King has tired of you? ‘Twere better then that you had never been born. Why did you lose your virtue to such a man? You should have married as good women do and brought children to your lawful husband. Now what will become of you? The best thing you can do is throw yourself down from the tower of your house. Why don’t you do that?’

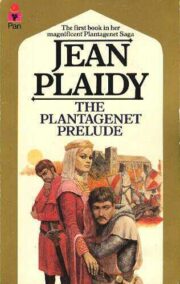

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.