‘He suffered towards the end, my lady, but never wavered from his purpose. We carried him right to the shrine and that made him happy. He died there in his litter but not before he had received the blessing. It was his wish that he be buried before the main altar in the Church of Saint James.’

‘And this was done?’

‘It was done, my lady.’

‘Praise be to God that he died in peace.’

‘His one concern was for your welfare.’

‘Then he will be happy in Heaven for when he looks down on me he will know I can take care of myself.’

‘Before he died he received an assurance from the King of France, my lady.’

Eleonore lowered her eyes.

There would be a wedding. Her own. And to the son of the King of France. Louis the Fat would not have been so eager to ally his son with her had she not been the heiress of Aquitaine.

How could she grieve? How could she mourn? Her father, who had planned to get an heir who would displace her, was no more. His plans were as nothing.

There was one heir to Aquitaine. It was Duchess Eleonore.

Young Louis was very apprehensive. He was to travel to Aquitaine, there to present himself to his bride and ask her hand in marriage. That was a formality. His father and hers had already decided that there should be a match between them.

What would she be like - this girl they had chosen for him? At least she was a year younger than he was. Many royal princes were married to women older than themselves. That would have terrified him.

How he wished that he had remained in Notre-Dame. He longed for the ceremonies in which he had taken part, the sonorous chanting of priests, the smell of incense, the hypnotic murmur of voices in prayer. And instead there must be feasting and celebration and he must be initiated into the mysteries of marriage.

He wished that he were like so many youths; they lived for their dalliance with women; he had heard them boasting of their adventures, laughing together, comparing their brave deeds. He could never be like that. He was too serious; he longed for a life of meditation and prayer. He wanted to be good. It was not easy for rulers to shut themselves away from life; they had to be at the heart of it. They were said to govern, but often they were governed by ministers. They had to go to war. The thought of war terrified him even more than that of love.

The King lay at Bethizy and thither had come the most influential of his ministers, among them the Abbe Suger. The marriage between young Louis and Eleonore of Aquitaine had won their immediate approval. It could only be to the good of the country that the rich lands of the south should come to the crown of France. The King could be assured that his ministers would do all in their power to expedite the marriage.

The Abbe Suger would himself arrange the journey and remain beside the Prince as his chief adviser.

The King, who knew that death could not be far off, was anxious that the progress from Bethizy to Aquitaine should be absolutely peaceful. There must be no pillaging of towns and villages as the cavalcade passed through. The people of the kingdom of France and the dukedom of Aquitaine must know that this was a peaceful mission which could bring nothing but good to all concerned.

He could rest assured that his wishes would be carried out, the Abbe told him.

He sent for his son. Poor Louis! So obviously destined for the Church. And he had heard accounts of Eleonore. A voluptuous girl ripe for marriage, young as she was. She would know how to win Louis, he was sure of that. Perhaps, when he saw this girl who by all accounts was one of the most desirable in the country - and not only for her possessions - he would realise his good fortune.

He told him this when he came to his bedside. ‘Good fortune,’ he said, ‘not only for you, my son, but for your country, and a king’s first duty is to his country.’

‘I am not a king yet,’ said Louis in a trembling voice.

‘Nay, but the signs are, my son, that you will be ere long. Govern well. Make wise laws. Remember that you came to the crown through God’s will and serve him well. Oh, my dear son, may all-powerful God protect you. If I had the misfortune to lose you and those I send with you, I should care nothing whatever either for my person or my kingdom.’

Young Louis knelt by his father’s bed and received his blessing.

Then he left with his party and took the road to Bordeaux.

The town of Bordeaux glittered in the sunshine; the river Garonne was like a silver snake and the towers of the Chateau de l’Ombriere stretched up to a cloudless sky.

The Prince stood on the banks of the river gazing across. The moment when he was brought face to face with his bride could not long be delayed.

He was afraid. What should he say to her? She would despise him. If only he could turn and go back to Paris. Oh, the peace of Notre-Dame! The Abbe Suger had little sympathy for him. As a churchman, he might have been expected to, but all he could think of - all anyone could think of - was how good this marriage was for France.

‘My lord, we should take to the boats and cross to Bordeaux. The Lady Eleonore will have heard that we are here. She will not expect delay.’

He braced himself. It was no use hanging back. What was not done today must be done tomorrow.

‘Let us go now,’ he said.

He was riding to the castle at the head of the small party he had taken with him. His standard bearer held proudly the banner of the golden lilies. He looked up at the turret and wondered whether she watched him.

She was there, exultantly gazing at the golden lilies, the emblem of power. Aquitaine might be rich but a king was necessarily of higher rank than a duke or duchess and even if the acknowledgement of suzerainty was merely a form yet it was there, and Aquitaine was in truth a vassal of France.

And I shall be Queen of France, Eleonore told herself.

She came to the courtyard. She had taken even greater care than usual with her appearance. Her natural elegance was enhanced by the light blue gown she was wearing; this was caught in at her tiny waist with a belt glittering with jewels. She was not wearing the fashionable wimple as she wanted to show off her luxuriant hair which she wore hanging over her shoulders with a jewelled band on her forehead.

She looked up at the boy on his horse as she held the cup of welcome to him.

Young, she thought, malleable. And her heart leaped in triumph.

He was looking at her as though bemused. He had never imagined such a beautiful creature; her serene eyes smiled into his calmly; the diadem on her broad high brow gave her dignity. He thought she was exquisite.

He leaped from his horse and, bowing, kissed her hand.

‘Welcome to Aquitaine,’ she said. ‘Pray come into the castle.’

Side by side they entered.

She told Petronelle when her sister came to her chamber that night: ‘My French Prince is not without charm. They have grace, these Franks. They make some of our knights seem gauche. His manners are perfect. At first though I sensed a reluctance.’

‘That passed when he saw you,’ said the ever-adoring Petronelle.

‘I think it did,’ replied Eleonore judiciously. ‘There is something gentle about him. They brought him up as a priest.’

‘I can’t imagine you with a priest for a husband.’

‘Nay, we shall soon leave the priest behind. I wish we need not wait for the ceremony. I would like to take him for my lover right away.’

‘You always wanted a lover, Eleonore. Father knew it and feared it.’

‘It is natural enough. You too, Petronelle.’

Petronelle sighed and raised her eyes to the ceiling. ‘Alas, I have longer to wait.’

Then they talked intimately about the men of the court, their virtues and their potentialities as lovers.

Eleonore remembered some of the exploits of their grandfather.

‘He was the greatest lover of his age.’

‘You will excel even him,’ Petronelle suggested.

‘That would be most shocking in a woman,’ laughed Eleonore.

‘But you will be equal to men in all things.’

‘I look forward to starting,’ said Eleonore with a laugh.

The Prince loved to listen to her singing and watch her long white fingers plucking the lute and the harp; she said, ‘I will sing you one of my own songs.’

And she sang of longing for love and that the only true happiness in love was through the satisfaction this could bring.

‘How can you know?’ he asked.

‘Some instinct tells me.’ Her brilliant eyes were full of promise; even he found a certain desire stirring in him. He no longer thought so constantly of the solemn atmosphere of the Church; he began to wonder what mysteries he and his bride would discover together.

She played chess with him and beat him. Perhaps she had had more practice. When he was learning to be a priest she had been brought up in court accomplishments. It was a lighthearted battle between them. When she had check-mated him she laughed and was delighted; it was like a symbol to her.

They walked in the gardens of the castle together. She showed him the flowers and the herbs which grew in the South. She told him how it was possible to make cures and ointments, lotions to beautify the skin and make the eyes shine, a draught to stir a reluctant lover.

‘Dost think that I shall need to make one for you -‘

He caught her hand and looked into her face.

‘No,’ he said, vehemently. ‘That will not be necessary.’

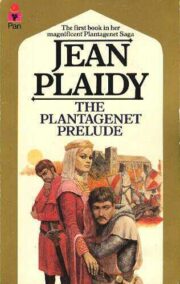

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.