‘Nay, my lady,’ he replied to his mother. ‘I could not have made a better choice. Becket and I understand each other. He has been a good Chancellor and when the Chancellor and the Archbishop of Canterbury are one and the same you will see how easy it is for us to carry out our plans.’

‘I shall pray that it is so,’ said Matilda. ‘But there has always been trouble between the Kings and the Church. The Church wants to take power from the State and it is for the Kings to see that they do not. In appointing this man as head of your Church you have put unlimited power into his hands.’

‘Becket wielded great power as Chancellor,’ said the King. ‘I found him easy to handle then.’

‘The King and his Chancellor, were inseparable,’ said Eleanor.

‘I could never understand this friendship with such a man,’ put in Matilda. ‘A merchant’s son! It puzzles me.’

‘Believe me,’ said Henry, ‘there is no man in England more cultured.’

‘It is impossible,’ snapped Matilda. ‘You deceive yourself.’

‘I do not. He is a man of great learning, and has a natural nobility.’

‘The King loves him as though he were a woman,’ put in Eleanor scornfully.

Henry threw a venomous glance in her direction. Why did she take sides with his mother against him? Ever since he had put young Geoffrey in the nursery she had manifested this dislike of him.

‘I esteem him as a friend,’ corrected Henry angrily. ‘There was never any other of my servants who could amuse me as that man did.’

‘And not content with making him your Chancellor you must give him the chief archbishopric in the kingdom as well.’

‘My mother, my wife! This is politics. This is statecraft. My Chancellor is my Archbishop. My Chancellor must be loyal to the State and since my Archbishop is also my Chancellor how can he go against that which is beneficial to the State?’

‘So this is your idea of bringing the Church into submission to the State,’ said Matilda. ‘I hope it works.’

‘Fear not, Mother. It will work.’

‘Your Archbishop is indeed a worldly man.’ Eleanor turned to Matilda. ‘You will know that this man lives in unsurpassed splendour. He maintains seven hundred knights and the trappings of his horses are covered in gold and silver. I heard that he receives the highest in the land.’

‘And as Chancellor so he should,’ retorted the King.

‘An upstart,’ said Matilda. ‘Having been born humble he must continually let people know how noble he has become.’

‘You, my dear Mother, were born royal but I believe you never allowed any to forget your nobility.’

‘Oh, but this fellow was quite ostentatious,’ said Eleanor. ‘I have heard it said that he lived more splendidly than you ever did.’

Henry laughed indulgently. ‘He has a taste for such luxury. As you say he was not born to it but acquired it. Therefore he prized it.’

‘He has bewitched you,’ Eleanor told him.

He gave her a glance of distaste. Why did she bait him? She was jealous he knew. So she still had some feeling for him. She had disliked his friendship with Becket almost as much as she hated his love affairs.

She went on to discuss the extravagances of Becket.

‘At his banquets there must be every rarity. I heard that he paid seventy-five pounds for a dish of eels.’

‘One hears this gossip,’ said the King. ‘If Thomas was extravagant it was to do me honour. He is my Chancellor and I remember when he went to France in great state it was said that I must indeed be a wealthy man since my Chancellor travelled as he did.’

‘Clever he may be,’ said Matilda, ‘but I warn you. Make sure he is not too clever.’

‘You will see what a brilliant move this is on my part. This will be an end to the strife between Church and State.’

It was only a day or so after that conversation that Henry fell into one of the greatest rages that ever had overtaken him.

A messenger had arrived from Canterbury, bringing with him the Great Seal of Office. Henry looked at it in dismay for he began to understand what it meant. There was a letter from Thomas and as the King read it a mist swam before his eyes.

‘By God’s eyes, Thomas,’ he muttered between his teeth. ‘I could kill you for this.’

Thomas had written that he must resign his Chancellorship for he could not reconcile his two posts. The Archbishop must be quite apart from the Chancellor. Thomas had a new master. The Church.

Henry’s rage almost choked him. This was the very thing his mother had prophesied. This was the implication behind Eleanor’s sneers. He had believed in Thomas’s love for him; he had thought their friendship more important than anything else. So it had seemed to him. But not to Thomas.

He remembered Thomas’s words. It would be the end of their friendship.

Only if the Chancellor and the Archbishop were as one could Henry’s battle with the Church be won. If Thomas was going to set himself up on one side while he was on the other there would be conflict between them.

His grandfather had fought with the Church. Was he to do the same … with Thomas?

And he had thought himself so clever. He was going to avoid that. He was going to put his friend into the Church so that the Church would be subservient to the State - so that the King would rule and none gainsay him. Henry Plantagenet had planned to have no Pope over him.

And this man … who called himself his friend, to whom he had given so much … had betrayed him. He had accepted the Archbishopric and resigned from the Chancellorship.

‘By God, Thomas,’ he said, ‘if you wish there to be war between us, then war there shall be. And I shall be the victor. Make no mistake about that.’

Then the violence of his rage overcame him. He beat his fist against the wall and it was Thomas’s face he saw there. He kicked the stool around the chamber and it was Thomas he kicked.

None dared approach him until his rage abated. They all knew how violent the King’s temper could be.

Eleanor and Henry took their farewell of Matilda and travelled to Barfleur. The King had declared he would spend Christmas at Westminster.

His anger against Thomas had had time to cool. He reasoned with himself. Thomas had reluctantly taken the Archbishopric and he had in some measure forced it upon him. Therefore he must not complain if Thomas resigned the Chancellorship. It was disappointing but he might have known that Thomas would do exactly as he had done. He was after all a cleric.

There will be battles between us, thought Henry. Well, there have always been battles of a kind. It will be stimulating, amusing. I long to see Thomas again.

Eleanor said: ‘I’ll dare swear your Archbishop is trembling in his shoes as he awaits your arrival.’

‘That is something Thomas would never do.’

‘If he has heard what a mighty rage you were in when you heard he had resigned the Chancellorship, he will surely not expect you to greet him lovingly.’

‘He is a man of great integrity. He would always do what he believed to be right.’

‘So he is forgiven? How you love that man! I’ll warrant you can scarcely wait to enjoy his sparkling discourse. And only a short while ago you were cursing him. What a fickle man you are, Henry!’

‘Nay,’ answered Henry, ‘rather say I am constant, although I may be enraged for a time that passes.’

‘Your servants know it. All they must do is anger you, keep out of your way and then return to be forgiven.’

‘You know that is not true,’ he said and closed the conversation.

Do not think, she mused, that I may be thrust aside for a while and then taken back. You may be in a position to subjugate others but not Eleanor of Aquitaine. I shall never forget that you placed your bastard into my nurseries to be brought up with my sons. Richard was now six. She had watched his manner with his father. He was all for his mother, and would be more so. And Richard was the most beautiful and most promising of their children. Henry the eldest had already gone to Becket and clearly doted on the man. Little Geoffrey was too young to show a preference. Henry could have the adulation of his little bastard and be content with that, but when the time came it was his legitimate children who would inherit their parents’ possessions. Richard should be Duke of Aquitaine; on that she had decided. He could already sing charmingly and loved to play the lute.

At Barfleur they waited for the wind to abate. It would be folly to set to sea in such weather. But day after day it raged and it became apparent that they could not be in Westminster for Christmas.

There were festivities at Cherbourg, but it was not the same. Eleanor would have liked to be with her children on Christmas Day. She had planned an entertainment for them with minstrels and dancers and she knew that young Richard would have enjoyed that and shone too above the rest of them. He would have made bastard Geoffrey seem an oaf.

It was not until nearing the end of January that they set sail.

When they reached Southampton Thomas Becket and their son Henry were waiting there to greet them. Henry, eight years old, had grown since they last saw him. He knelt before them and his father laid his hand on his head. He was pleased with his son’s progress. There was nothing gauche about the boy. That was due to Thomas.

And Thomas? He and the King looked at each other steadily. Thomas was clearly uncertain what to expect. Then the King burst out laughing.

‘Well, my Chancellor that was and my Archbishop that is, how fare you?’

And all was well between them.

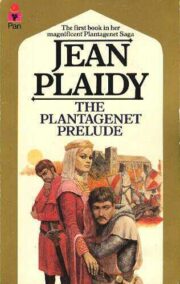

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.