When the King knew what Thomas had done he was furious. He strode into the Chancellor’s apartments, his eyes wild, his face scarlet, his tawny hair on end so that he looked more like a raging lion than ever.

‘So, Master Becket, you have decided to take the crown! It is you who rule England and Normandy then?’

Thomas looked at him calmly.

‘It is this matter of the Abbess which grieves you, my lord.’

‘Grieves me! I tell you I am so wild with fury that I myself would hold the burning iron that shall put out those haughty eyes.’

‘So you have sentenced me without hearing my case.’

‘I am your King, Becket.’

‘I know it well, my lord.’

‘And you fear not to anger me ?’

‘I fear only to do what I know to be wrong.’

‘So you are judging us, are you? You, Thomas Becket, clerk of the counting-house, would judge your King!’

‘It is only God who will do that, my lord.’

‘You and your piety! You make me sick, Thomas. You are a man and posing always as a saint. One of these days I shall catch you out. How I look forward to that! And if you value your life you will withdraw your request to the Pope on account of Stephen’s daughter.’

‘I have sent her case to the Pope with her consent, my lord.’

‘Know this. There is no one who gives consent here but the King.’

‘There is a higher power.’

‘You would serve the Pope then … rather than your King?’

‘I would serve the right, my lord.’

The King’s fury abated a little. It was strange how he found it difficult to keep up a quarrel with Thomas.

‘Don’t be a fool, Thomas. Would you have me lose Boulogne?’

‘If God wills it.’

‘Have done with this talk of God. I have never known Him go into battle with my grandfather or my great-grandfather.’

‘They asked help many a time I doubt not.’

‘His help maybe but they did not sit and wait for Him to make their conquests. If they had, they would have waited a long time. I am not going to lose Boulogne. If I did, what would happen? What if it fell into the hands of some evil lord who knew not how to govern? Nay, Thomas, you’re a chancellor not a priest. Forget your cleric’s robes. I can take Boulogne with the utmost ease through this marriage. It will save war and conflict. And all because a nun is asked to relinquish her vows and take a husband.’

‘It is wrong.’

‘Have done.’

‘Nay, my lord, I cannot.’

‘Send another messenger to the Pope. Tell him that the lady has consented to the marriage. Let it be known that you ask for no barriers to be put in the way of this match.’

‘I cannot do it, my lord.’

The King’s face was suffused with blood. He took a step towards Thomas, his hand raised to strike him. Thomas stood impassive. For a few seconds Henry seemed as though he would fall on the Chancellor and tear him apart or at least call to his guards to arrest the Chancellor. His eyes, wild with rage, looked into Thomas’s cool ones, and suddenly he turned and picking up a stool threw it against the wall.

‘I am defied,’ he cried. ‘Defied by those whom I have befriended. They work against me in secret. By God, I’ll be revenged.’

Thomas said nothing. He stood there, then with a cry of rage the King threw himself on the floor and seizing a handful of rushes gnawed them in his rage.

Thomas went out and left him.

He had seen Henry in such a rage that he could not control his temper on one or two occasions, but that anger had never been directed against him before.

He waited for what would happen next.

There was a message from the Pope. He had received news from both the King and the Chancellor concerning the Abbess of Romsey. Pope Alexander was in a very uneasy position. He had been elected at the conclave a very short time before and there had been certain opposition to his taking the papal crown. As that opposition was backed by the Emperor Barbarossa, he did not feel that the papal crown was very secure.

He dared not offend Henry Plantagenet who was not only King of England but fast becoming the most powerful man in France. The fact that the King’s Chancellor differed from his master and was in the right was a very special reason for giving the King what he wanted, for the fact that one of his servants was against him and he himself was in the wrong would make the King doubly angry if the Pope sided against him. Therefore Alexander granted the dispensation. When he received it the King roared with gratified laughter. The first thing he did was to send for Thomas Becket.

‘Ha!’ he cried, when his Chancellor stood before him. ‘Have you heard from your friend the Pope, Thomas?’

‘No, my lord. Perchance it is early yet.’

‘Not too early for me to have received a reply. He’s a wise fellow, Thomas. Wiser than you, my godly Chancellor. I have the dispensation here.’

Henry was gratified to see Thomas turn a shade paler.

‘It cannot be.’

‘See for yourself.’

‘But …’

Henry gave his Chancellor an affectionate push.

‘How could he do otherwise? His state is not too happy. Why, Thomas, you should study his ways. If you do not, you could mortally offend those who could do you harm. Sometimes it is better to serve them than what you call the right. Oh, you do not believe me? Strange as it may seem I like you for it. But I have the dispensation and our bashful Abbess will soon find herself in the marriage bed and I shall still have control over Boulogne.’

Thomas was silent and the King went on: ‘Come, Thomas, applaud my skill. Was it not a good move, eh?’

Thomas was still silent.

‘And what shall I do with my Chancellor who dared to go against my wishes? I could send him to a dungeon. I could put out his eyes. I fancy that would hurt you most. It does most men. To be shut away from the light of the sun, never to see again the green fields. Ah, Thomas, what a fool you were to offend your King.’

‘You will do with me as you will.’

‘I am a soft man at times. Are you not my friend? I could have had you killed, and looked on and seen it done with pleasure. But methinks had I done so I should never have known a moment’s peace after. It is good to have friends. I know that you are mine and that you do in truth serve only one with greater zeal and that is God or Truth, or Righteousness … call it what you will. I like you, Thomas. Know this. If you are my friend, I am yours.’

Then the King put his arm through that of Thomas Becket and together they went out of the chamber.

The friendship between them was greater than ever.

When Henry returned to England the two were constantly together and it was noted that Henry found the society of his Chancellor more rewarding than that of any other person. The rift between himself and Eleanor had widened. She had never forgiven him for bringing the bastard Geoffrey into the royal nurseries and he taunted her by making much of the boy. He liked to escape to the domestic peace of Woodstock. His love for Rosamund did not diminish. Perhaps this was due to the fact that she made no demands. She was always gentle and loving, always beautiful. They had their little son, too, and she was pregnant once more. She gave to him the cosy domesticity which kings can so rarely enjoy, and he delighted in keeping her existence a secret; and none but her servants knew that he visited her and they realised that it would go ill with them if through them the secret was divulged.

The King was happy. His kingdom was comparatively peaceful. He was watchful, of course, but then he would always have to be that. For a time he could stay peacefully in England, and he could enjoy the company of his best friend, Thomas Becket.

Sometimes he asked himself why he loved this man. There could not have been one more different. Even in appearance they presented a contrast. Tall and elegant Thomas, the stocky, carelessly dressed King. Thomas’s love of fine clothes amused Henry. He teased him about it constantly. Why should he, the all-powerful King who could have chosen the most nobly born in his kingdom to be his companions, care only for the society of this man? Thomas was fifteen years older than he was. An old man! So much that Thomas believed in the King disagreed with; and Thomas would never give way in discussion. The King’s temper could wax hot, but Thomas would remain calm and stick to his point. Henry was amused that in spite of Thomas’s aesthetic appearance and concern with spiritual matters, at heart he loved luxury. There was no doubt that he did. His clothes betrayed him. He could also be merry at times. Henry liked to play practical jokes on his friend and Thomas responded. The King would sometimes howl with laughter at some of these, even those against himself. There was no one at his court who could divert him as Thomas Becket could.

They were together constantly. When the King made his frequent peregrinations about the countryside, his Chancellor rode beside him. Sometimes they went off together incognito and sat in taverns and talked with the people. No one recognised the tall dark man with elegant long white hands and his younger freckle-faced, sturdy companion, whose hands were square, and chapped with the weather. An incongruous pair those who met them might have thought, and few were aware that they were the King of England and his Chancellor.

Henry liked nothing better than to score over his Chancellor. He had never forgotten the affair of the Boulogne marriage.

One winter’s day when he and the Chancellor were riding through London, with the cold east wind howling through the streets, Henry looked slyly at his friend. Thomas hated the cold. He would wear twice as many clothes as other men, and although he ate sparingly his servant had to prepare beef steaks and chicken for him. His blood was thin, said the King; he was not hardy like the sprig from the Plantagenet tree. Thomas’s beautiful white hands were protected by elegant but warm gloves, and even in such a bitter wind which was now buffeting the streets of London the King’s hands were free. Gloves, he always declared, hampered him.

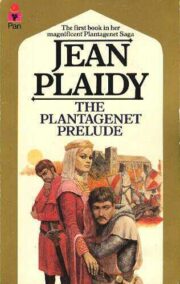

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.