Henry liked to plague him while he admired him.

‘A churchman,’ he would say, ‘yet you live like a king.’

‘Rather say a king lives like a churchman.’

Every day fresh rushes were strewn on his floors; he used green boughs in summer and hay in winter; but it must always be fresh.

‘Your cleanliness is greater than your godliness,’ pointed out the King.

‘Why should not the two go hand in hand, Sire?’ asked Becket.

‘Is it meet for a man of God to display fine gold and silver plate on his table?’

‘If he puts them there for love of his friends,’ answered Becket.

The King would put an arm about the Chancellor’s shoulders. ‘One of these days I will show you for the coxcomb you are,’ he mocked. ‘Look at your table; look at your home! Should you not go out into the world with rod and scrip and preach religion?’

‘I go out with the rod of my office and preach of justice,’ replied Thomas.

‘Good Thomas, you amuse me and for that I would forgive you all your sins.’

‘Let us hope, sire, that that other King who alone can pardon our sins is as lenient with you.’

And so they grew closer together and hardly a day passed when Becket was not in the company of the King.

Chapter IX

THE ABBESS BRIDE

While Eleanor was awaiting the birth of her child in the palace and Rosamund was at Woodstock also awaiting the King’s child, Henry sent for Becket as he wished to discuss the proposed marriage between his son Henry and the little Princess of France.

He was as usual delighted to see the Chancellor.

‘I know not how you will find the French King,’ said Henry. ‘As you know the Queen was his wife and she rid herself of him to marry me.’

‘I know it well,’ said Becket.

‘He was somewhat jealous I believe, and loath to let the Queen go, but the Queen was determined. She’s a determined woman as you know also, Chancellor.’

‘I had gathered so,’ answered Thomas.

‘Now this methinks is a situation which will appeal to your humour as it appeals to mine. My son and the Queen’s son Henry shall be the bridegroom of Louis’s daughter by his second marriage. Do you think that is not an amusing situation?’

‘I think it a very suitable one, my lord, since it will secure alliance with the King of France and little could be more beneficial to you at this time.’

‘So thought I,’ said the King. ‘It is years before the marriage can take place. My son is three years old. The Princess Marguerite is one. But that will be no impediment to the ceremony as it would be to the consummation. We shall not put the babies to bed together … yet.’

‘I should think not.’

‘Poor innocents! Still it is the lot of royal children. You should be thankful, Chancellor, that you were not a royal boy or they might have married you when you were in your cradle and that would not have been to your liking, would it?’

‘I have never had any fancy for the marriage bond.’

‘Nay, you’re a strange man, Becket. You care nothing for women which seems strange to a man like myself who cares very much for them. You know not what you miss. It is a taste which never wearies. It is only that one wishes now and then to change one’s partner in the game.’

‘The Queen would not wish to hear such sentiments expressed.’

‘You are right, Becket. My Queen is a woman of strong opinions. You will have to mind your step with her … as even I do.’

‘The Queen is one who is accustomed to being obeyed.’

‘Indeed you speak the truth. I have managed very well during our life together. I always contrive to see that she is either going to have a child or having one. It is a very good way of curbing her desire to rule.’

‘It is not one which can continue for ever.’

‘As the Queen tells me. She says when this one is born there must be a respite.’

‘It is better for her health that this should be so.’

‘I am expecting a child in another quarter, Becket.’

‘I grieve to hear it, Sire.’

The King burst into loud laughter and slapped Becket on the back.

‘You know full well that a king who cannot get heirs is a curse to the nation.’

‘I know it is well for a king to get legitimate heirs.’

‘My grandfather used to say that it is well for a king to have children - inside and outside wedlock, for those who are of royal blood will be loyal to it.’

‘It is not an infallible recipe for loyalty, sire.’

‘Oh come, Becket, you are determined to reproach me. I won’t have it. Do you hear me?’

‘I hear very well, my lord.’

‘Then take heed for if you offend me I could turn you from your office.’

‘My lord must turn me from it if he will and I shall pray that he finds another to serve him as well as I should.’

‘I never would, Thomas. I know it and for this I will stomach a little of your preaching. But not too much, man. Remember it.’

‘I will remember, my lord.’

‘You have seen my fair Rosamund, Becket. Is she not beautiful? More so in her present state than when I first saw her. It surprises me that my feeling for her does not pall. I love the girl, Becket. You are silent. Why do you stand there with that smug expression on your face? How dare you judge me, Thomas Becket! Are you my keeper?’

‘I am your Chancellor, my lord.’

‘Not for long … if I wish it. Remember that, Becket. And if you are going to tell me that I should give up Rosamund I am going to fall into a temper, and you know my tempers, Thomas.’

‘I know them well, Sire.’

‘They are not pleasant to behold, I believe.’

‘There you speak truth, my lord.’

‘Then it would be well for those around me not to provoke them. I have settled her at Woodstock and I am having a bower built there. A house in the forest … surrounded by a maze of which only I shall know the secret. What think you of that?’

‘That it is a plan worthy of you, my lord.’

The King narrowed his eyes and laughed again.

‘You amuse me, Thomas,’ he said. ‘You stand in judgement. You reproach me. You disapprove of me, but you amuse me. For some reason I have chosen to make you my friend.’

‘I am also your Chancellor, Sire,’ said Becket. ‘Shall we discuss the mission to France?’

For such a mission Thomas could display great magnificence without any feeling of shame. All the scarlet and gold trappings which he so much enjoyed could be brought into play without any feeling of guilt on his part because what he was doing now was for the glory of England. He could not go into France like a pauper. During his journey he must impress all who beheld him with the might and splendour of England.

A troop of soldiers accompanied the procession, besides butlers and stewards and other servants of the household; there were members of the nobility who were to form part of the embassy, and of his own household he took two hundred horsemen. He had brought dogs and birds as well as twelve pack-horses with their grooms, and on the back of each horse sat a long-tailed ape. The procession was followed by wagons which carried Thomas’s clothes and others in which were stored the garments of the rest of the party with gifts which would be judicially distributed at the court of France. And after these were larger wagons one of which was furnished as a chapel for Thomas’s use, and another for his bedchamber. In yet another were utensils for cooking so that the party could stop wherever was deemed desirable.

As this magnificent cavalcade - the like of which had never been seen before - passed through France, people came out of their houses to watch it.

‘What manner of man can the King of England be?’ they asked each other. ‘He must be the richest man in the world since this man, who is only his Chancellor and servant, travels in such state.’

News was brought to Louis that the Chancellor was on his way and that the magnificence of his retinue had startled everyone who had seen it. Determined not to be outdone he gave orders that when the party arrived in Paris no merchant was to sell his goods to any member of the English party. France was to be host to the English and they must have what they would and there should be no question of their paying.

Thomas guessed that this might be the King’s wish and in order not to put himself under any obligation - which might be detrimental to his mission - he sent his servants out secretly to buy any provisions they would need. He did however accept lodgings at the Temple. There he kept a sumptuous table of which all who came to see him were invited to partake.

In the face of such extravagance the French could only retaliate in kind. They must not be made to look less hospitable, less elegant, less generous than the English.

Louis received Thomas with every honour. How could he refuse the hand of his daughter to the son of a king who came to him in such a manner?

He had at first been uneasy. His little daughter Marguerite was but a year old. Poor child, how innocent she was, unaware as yet as to what this mission meant! She would in time go to the English court there to be brought up as the bride of Henry who would, if all went well, become the King of England with little Marguerite that country’s Queen.

Louis still thought of Eleanor and that state of passion to which she had introduced him. He feared he would never forget her and even now he was reminded of how she had left him, and almost immediately her divorce was secured had married Henry Plantagenet whose mistress she had already been.

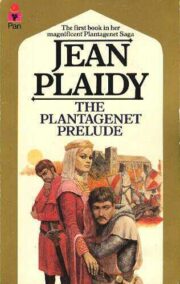

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.