‘There is not a more powerful man in England,’ cried Henry, his eyes gleaming. ‘Victory is assured.’

But he was too clever to let that change his preparations which were going to be as thorough as though he were facing the most formidable army in the world.

It was a January day when he sailed for England with his fleet of thirty-six ships and landed at Bristol. There he found men of the West Country ready to rally to his cause.

Sadly Eleonore missed him. He had absorbed her life to such an extent that she asked for no other lover. She threw herself into the task of looking after his affairs and her friendship with her mother-in-law the Empress ripened. The two women admired each other and although their strong temperaments often clashed, for neither would give way in the slightest degree in her opinions to please the other, they never forgot that discord between them would be detrimental to Henry, and for both of them he was the centre of their lives.

Eleonore had her little court about her. Gallant men sang her songs and composed verses of their own. Many of them were addressed to her, and because of her reputation, which would always be with her, many of them were hopeful. But Eleonore was devoted to her Duke. They all knew that, but could such a woman be expected to keep her sensuality smouldering, not allowing it to burst into fire before the return of her lord which might be who knew when?

But Eleonore was so enamoured of her husband that none of those about her pleased her. Moreover he had not been gone for more than a month when she knew for certain that she was pregnant and she began to think exclusively of the child.

Matilda was delighted. ‘You’ll have sons,’ she declared. ‘You are like me. All my children were sons and there were three of them. I might have had twenty sons if I’d had a fancy for my husband, but I never did, though many women found him attractive …’

She looked obliquely at Eleonore who nodded gravely, remembering the charm of him who had earned for himself the name of Geoffrey the Fair.

‘Yes,’ went on Matilda, ‘he had many a mistress. It never bothered me. He was my husband when he was but fifteen. I thought him a foolish boy and I never took to him. I bore a grudge against him because they’d given him to me. First they gave me an old man and then a young boy. It wasn’t fair. You know they might have married me to Stephen.’

‘English history would have been different if they had.’

‘All those wretched civil wars would never have taken place.’ Matilda’s eyes grew dreamy. ‘Yes, if my father had known his only legitimate son was going to be drowned at sea, he would have married me to Stephen. I’m certain of it. I would have been better for him than that meek wife of his and he would have been better for me. He was one of the handsomest men you ever saw. I think the biggest blow in my life was when I heard that he had taken the crown. I’d always believed he would stand by me. Crowns, my daughter, what blood has been shed because of them - and more will most certainly be!’

‘Not Henry’s,’ said Eleonore firmly.

‘Nay, not Henry’s. But what if it should be Stephen’s?’

She was silent for a while. Then she went on: ‘Stephen must know that that wild boy of his cannot inherit the crown. The people would never accept Eustace. And then he has William. That woman’s children. It always infuriated me that she had the same name as mine. If only Stephen could be made to see reason.’

‘Would he call it reason to give up the crown to Henry?’

‘He cannot live long. What if there was a truce? What if they made an agreement? Stephen to rule as long as he lives and then Henry to be the King of England.’

‘Would a man pass over his own son for another?’ ‘If it were justice perhaps.

If it would stop war. If it would give England what she always needs, what she had in the times of my father Henry I and my grandfather William the Conqueror. Those are the strong men England needs and my son, your husband, is one of them.’

‘Stephen would never agree,’ said Eleonore. ‘I cannot believe any man would pass over his own son.’

Matilda narrowed her eyes.

‘You do not know Stephen,’ she said. ‘There is much that is not known of Stephen.’

News came of Henry’s progress. It was good news. All over England people were rallying to his banner. Eustace had made himself unpopular and people were weary of continual civil war. They recalled the good old days under King Henry, whose stern laws had brought order and prosperity to the land. He had not been called the Lion of Justice for nothing. There was something about young Henry Plantagenet that inspired their confidence. He was of the same calibre as his grandfather and great-grandfather.

There was no doubt in Eleonore’s mind that he would succeed. The question was when, and how long would it be before they were united?

She had left Matilda and travelled to Rouen as she wished the birth to take place in that city and there she prepared for her confinement.

She was exultant on that hot August day to learn that she had borne a son. How delighted Henry would be. She immediately despatched messengers to him. The news would cheer him wherever he was.

She decided that his name should be William. He was after all the son of the Duchess of Aquitaine and William was the name so many of the Dukes of that country had borne. Moreover Henry’s renowed great-grandfather, the mighty Conqueror, had been so called.

As she lay with her child in her arms her women marvelled at the manner in which childbirth had softened her. They had not seen her with her daughters. Now and then she thought of them - little Marie and Alix - and wondered whether they ever missed their mother. She had loved them dearly for a while after their birth. There had been occasions when she would have liked to devote herself to them. She thought of the infants in her arms, tightly bound in their swaddling clothes that their limbs might grow straight. The poor little things had offended her fastidiousness. Bound thus how could it be otherwise for they were not allowed to emerge from their cocoons for days on end, disregarding the fact that the poor little things must perform their natural functions.

It should be different with her son. She would watch over him, assure herself that his limbs would grow straight without the swaddling clothes.

She loved him dearly - a living reminder of her passion for Henry - and she knew that the best news she could send him was the birth of a boy. Perhaps she should have called him Henry. Nay, she was implying that she had brought him Aquitaine and until he could offer her the crown of England she was bringing more to the marriage than he was. It was well to remind him that they stood equal.

‘The next son must be Henry,’ she wrote to him. ‘But our firstborn is named after my father and grandfather and the most illustrious member of your family, your great-grandfather whom it is said few men rivalled in his day or ever will after.’

While she was lying-in the most amazing news was brought to her. She wished to rise from her bed and make a great feast not only of roast meats but of song and story to celebrate the event, for nothing could have more clearly showed that God was on the side of the Duke of Normandy.

Stephen and Henry had faced each other at Wallingford and were about to do battle when Stephen decided that instead of fighting he would like to talk to Henry. It had been difficult to persuade Henry to do this for he was certain of victory and believed that the battle might well decide the issue. However, he finally agreed and as the result of their meeting, to the astonishment of all, the battle did not take place.

Eustace, who was burning with the desire to cut off the head of the man he called the upstart Henry and send it to his wife, was so angry at what he thought was the cowardice of his father that he gave way to violent rage. He had never been very stable but even his most intimate followers had never seen his control desert him to such an extent.

He would raise money, he declared, and he would fight the battles which his father was afraid to face. Did Stephen not understand that it was his heritage which Henry was trying to take from him? He, Eustace, was the heir to the throne of England and he was not going to allow his father’s weakness to bestow it on Henry.

In vain did his friends try to restrain him; he reminded them that he was the commander of his armies and marched to Bury St Edmunds, where he rested at the Abbey, and when he had refreshed himself he demanded that the Abbot supply him with money that he might go into battle without his father’s help against Henry of Normandy. The Abbot declared that he had nothing to give him whereupon Eustace demanded to know why the treasures of the Abbey should not be sold to provide him with what he needed.

The Abbot took the opportunity, while he pretended to consider, of locking away the treasure. Then he refused.

Calling curses on the Abbot and his Abbey, Eustace rode away, but not far. He ordered his men to take what they wanted from the countryside and every granary was plundered, every dwelling robbed, but the main object of his pillage was to be the Abbey. His soldiers returned to it and forced the monks to tell them where the treasure was hidden. When they had plundered the place, Eustace led them back to the nearest castle to make merry.

He sat at table to eat of the roasting meats which his servants had prepared, his anger still within him. He was going to make war on Henry of Normandy, he declared; he was going to drive him from the shores of England and very soon they would see him, Eustace; crowned king.

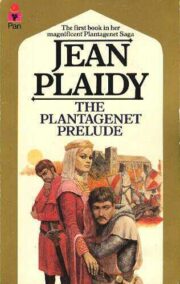

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.