‘Never!’ cried Geoffrey vehemently.

‘Have you forgotten that she would bring us Aquitaine?’

‘You cannot marry that woman.’

‘And why indeed not?’

‘She … she is married to the King.’

‘But Father, there is to be a divorce.’

‘There never will be.’

‘There will be. And if there is and she is free, you and my mother will rejoice. You must. Think of Aquitaine.’

‘You cannot marry Eleonore,’ cried Geoffrey.

‘I can when she is free.’

Geoffrey was silent for a few moments. ‘Nay,’ he said. ‘You could not … not if she were free and even though she brought you Aquitaine. I would never give my consent.’

Henry’s temper, which could be terrible, was beginning to rise.

‘Should I need your consent?’

‘You would need it if you would be my heir.’ Geoffrey looked steadily at his son. ‘In view of what happened between myself and the Queen of France I would never consent to the marriage.’

‘What mean you by that?’

‘I have known her well … intimately. You understand?’

Henry stared at his father.

Geoffrey had risen to his feet. He strode to the door.

He looked back at his son. ‘For that reason,’ he said, ‘I would never give my consent to the marriage, never … never …’

They were on their way to Paris. Henry had raged and fumed. He had cursed his father, the old Abbe Suger and everyone who was putting an obstacle between him and his marriage with Eleonore.

So she was a woman of strong passions. He had known that. So she had adventured during the crusade she had made to the Holy Land. There were rumours about her relationship with her uncle and a Saracen, and his own father had admitted to committing adultery with her. Well, she was Eleonore and unique. The fact that she had passed through these adventures made her all the more desirable to him. Drama encircled her. Many a prince had his bride found for him and he was given a simpering virgin for whom he could have little fancy. He was not like other princes. He had always known he was unique. A great future lay before him and that future was going to be shared with Eleonore. The obstacles which people were putting in his way were going to be thrust aside. He would arrange that.

And now to Paris. He would see her there. She would watch the ceremony when he swore fealty to her erstwhile husband, and at night he would creep into her bedchamber where they would make love and plans.

So although he had raged against his father and all those who stood in his way, he was now content. He was certain of success. In the end and when it came it would be all the more enjoyable because it had not been easy to attain.

What a joy it was to embrace her, to indulge in that violent and compulsive love-making. There was no one like her. Eleonore was different - a tigress compared with whom all other women were tame lambs. Moreover she could bring him Aquitaine. His father was being foolish to stand out against a marriage which could bring so much to Anjou and Normandy - and in due course England, and all because Eleonore had shared his bed. Poor Eleonore! A passionate woman married to a monk. What could be expected but that she should try out men now and then? It made her all the more appreciative of him, Henry, just as his amorous adventures made him certain that there was no woman in the world to compare with her.

She was equally delighted with him. His love-making lacked the grace of that of Raymond of Antioch, but Henry’s was as much to her taste. His youth was so appealing. She was sure that Henry was the man she wished to be her husband.

On the day of the ceremony she sat beside Louis on the dais and with glowing eyes watched the approach of her lover.

Henry knelt before the King of France and asked that his title of Duke of Normandy might be confirmed by him. If the King would grant his permission he would swear fealty to him and remember as long as he held that title that he was the vassal of the King of France.

He unbuckled his sword and took off his spurs. He laid them at the feet of the King of France and in return the King took a handful of earth which had been brought to him for this purpose as a symbol that he accepted Henry Plantagenet as Duke of Normandy.

Then there was feasting and celebration with Geoffrey seated on one side of the King and Henry on the other, and the comforting knowledge that the powerful Count of Anjou and the King of France were allies.

The lovers found opportunities to be together. They made love and talked of the future.

His father was against a marriage; the Abbe Suger was against it; but they would find a way.

‘My father must be won over,’ said Henry. ‘As for the old Abbe he can’t last for ever. He looks more feeble every day.’

‘It must be soon,’ said Eleonore, ‘for I have sworn to be your wife and Louis is not and never has been what I want in a husband.’

The fact that they were so often together was noticed of course. Courtiers smiled behind their hands. ‘First she tried out the father and now the son. No one can say that our Queen wastes time.’

Geoffrey was powerless to prevent their meetings and in due course the King’s advisers told him that the Queen and the young Duke of Normandy were causing scandal at court.

Louis sent for Geoffrey.

‘I think,’ he said, ‘that it would be advisable for you and your son to leave my court.’

Geoffrey was of the same opinion. He was angry that Eleonore and Henry should be lovers. He would have liked to resume that role with her himself. But when they met she behaved as though they had never been anything but acquaintances, and she certainly found the son preferable to his father.

‘They shall never marry while I live to prevent them,’ he vowed.

It would have been pleasant riding through the countryside if he had not had to leave Eleonore behind. There were however other matters to occupy Henry’s mind.

He was now undisputed Duke of Normandy and that was pleasant to contemplate. If only Eleonore could have forced Louis to divorce her he would be quite content … at the moment.

Geoffrey was determined not to discuss the matter of the proposed divorce. He had said it would never be granted and that put an end to the affair. He would attempt to arrange a suitable match for his son and that should not be difficult for the Duke of Normandy and his prospects would make young Henry a very desirable parti.

The day had grown very hot and they were travel-stained and weary. They were approaching Chateau du Loir when Geoffrey said, ‘Here is a pleasant spot to rest awhile. Let us stay here. Look, there is the river. I should like to bathe in it. That would be most refreshing.’

Henry was willing. They called a halt and the party settled down under the trees while Geoffrey and his son and a few of their attendants took off their clothes and went for a swim in the river.

They shivered delightedly in the cold water which was so refreshing after the heat of the day. They were loath to come out and when they did they lay on the bank talking.

‘Now that you are Duke of Normandy you will be ready to claim your other inheritance,’ said Geoffrey.

‘You mean … England.’

‘I do. The people would welcome you. They rejected your mother it is true and accepted Stephen, but they only did this because she made herself objectionable to them and Stephen was there and, weak as he is, he lacked your mother’s arrogance. They will be ready for you, Henry.’

‘Yes, soon I must go to England.’

‘You must make Stephen understand that you are the heir. He will try of course to give everything to his son Eustace.’

‘Never fear, Father. He shall not do that.’

‘You understand what a campaign like this means?’

‘There have been other campaigns, Father. You may trust me.’

As they talked of England and how Eustace was a weakling, heavy clouds arose and obscured the sun. Before they could dress there was a downpour. Wet through they returned to their camp.

That night Geoffrey rambled in his sleep. He was in a high fever.

When the news was brought to Henry he went at once to his father.

‘What ails you?’ he asked but Geoffrey looked at him with hopeless eyes.

‘It has come, Henry,’ he said. ‘As he said it would.’

‘You’re thinking of that man’s prophecy. He should be hanged for treason. ‘Tis nothing, Father. A chill, that’s all. You stayed overlong by the river.’

‘I am shivering with fever,’ said Geoffrey, ‘and more than that there is knowledge within me that this is the last time you shall see me in the flesh.’

‘I refuse to listen to such talk.’

‘Your concern does you credit, my son. If I am not to depart with my sins on me, you had better send me a priest.’

‘Stop talking so. Have you not had enough of priests?’

‘Methinks I need one to help me to heaven, son.’

Henry sent for a priest. The certainty that he was going to die was strong with Geoffrey. He wanted to talk to his son, explain to him the pitfalls which could entrap a young man. He himself had not enjoyed a happy married life. He did not want the same thing to befall Henry.

‘It should be a blessing, Henry, and it is often a curse. You should marry a good docile woman, one who will bear you many sons. At least Matilda gave me three. But my life with her, Henry, has been one continual battle. There was never love between us. I was ten years her junior. Never marry a woman older than yourself. She will dominate you.’

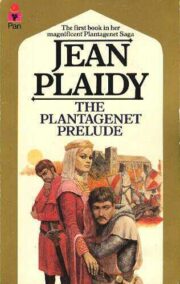

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.