‘If there were peace I should be able to ask God to grant your request.’

‘I will speak to the King,’ she said.

She did and the result was that there was peace between Theobald and Louis.

To Eleonore’s great joy she was pregnant. She was sure that Bernard had worked the miracle. All these years and no sign of a child, and now the union would be fruitful.

She had softened a little. She was planning for the child as a humble mother might have done. The songs she sang were of a different nature.

The members of the court marvelled.

In due course the child was born. A girl.

She was not disappointed. Like all rulers Louis had hoped for a son; yet, she demanded of her ladies, why should there be this overwhelming adoration of the male? ‘I was my father’s heiress although I was a woman,’ she reminded them. ‘Why should the King and I be sad because we have a daughter?’

The Salic law prevailed in France. This meant that no woman could rule. The crown would go to the next male heir. This law was all against Eleonore’s principles and she promised herself that she would not allow it to persist. Her daughter was but a baby yet and there was time enough to think of her future.

She was christened Marie and for more than a year after her birth Eleonore was content to play the devoted mother.

Life had become monotonous. Little Marie was past two years old. Eleonore was devoted to her but naturally the child was often in the company of her nurses. Eleonore continued to hold court. The songs had become more voluptuous again; they stressed the sorrows of unrequited passion and the joys of shared love.

Petronelle was her constant companion; Eleonore watched with smouldering eyes her sister and her husband together. What a passionate affair that had been! Something, sighed Eleonore, which was denied me.

She had at first been fond of Louis. He had been so overcome at the sight of her and was so devoted to her that she had developed quite an affection for him. It was not in her passionate nature to be contented with that. Louis might be her slave and it pleased her that he should be, but his piety bored her, and what was hardest of all to endure was his remorse.

He took a great interest in the Church and was constantly taking part in some ritual. He would return from such occasions glowing with satisfaction but it would not be long before he was sunk in melancholy.

He could not forget the sound of crackling flames and the screams of the aged and innocent as they had burned to death. The town itself had now become known as Vitry-the-Burned.

He would pace up and down their bedchamber while Eleonore watched him from their bed.

She knew that he would not be seeing her, seductively inviting with her long hair loose about her naked shoulders as she might be. He would be seeing the pitiless faces of men intent on murder; and when she spoke to him he would hear instead those cries for mercy.

How many times had she told him: ‘It was an act of war and best forgotten.’

And he declared: ‘To my dying day I shall never forget. Remember, Eleonore, all that was done was done in my name.’

‘You did your best to stop it. They heeded you not.’ Her lips curled. What a weakling he was! His men intent on murder did not obey him! And he permitted this.

He should have been a monk.

She was weary of him. She wished they had married her to a man.

Yet he was the King of France and marriage to him made her a queen. But she was also Eleonore of Aquitaine. She was never going to forget that.

So she listened to him wandering on in his maudlin way and she knew that she would not go on for ever living as she was at this time. Her adventurous spirits were in revolt.

She had made a brilliant marriage; she was a mother. But for her that was not enough. She was reaching for adventure.

The opportunity came from an unexpected quarter.

For many years men had sought to expiate their sins by making pilgrimages to Jerusalem. They had believed that by undertaking an arduous journey, which often resulted in death, they showed their complete acceptance of the Christian faith and their desire for repentance. They believed that in this way they could be forgiven a life of wickedness. There had been many examples of men who had undertaken this pilgrimage. Robert the Magnificent, father of William the Conqueror, had been one. He had died during the journey leaving his son but a child, unprotected from his enemies, but it was believed that he had expiated a lifetime’s sins by this gesture.

But while it was considered a Christian act to make a pilgrimage, how much greater grace could be won by taking part in a Holy War to drive the infidel from Jerusalem.

Ever since the seventh century Jerusalem had been in the possession of the Mussulmans, khalifs of Egypt or Persia. There was conflict between Christianity and Islamism, and at the beginning of the eleventh century the persecution of Christians in the Holy Land was at its most intense. All Christians living in Jerusalem were commanded to wear a wooden cross about their necks. As these weighed five pounds they were a considerable encumbrance. Christians were not allowed to ride on horses; they might only travel on mules and asses. For the smallest disobedience they were put to death often in the cruellest manner. Their leader had suffered crucifixion; therefore that seemed a suitable punishment for those who followed him.

Pilgrims who made the journey to and from Jerusalem came back with stories of the terrible degradation that Christians were being made to suffer. Indignation came to a head when a certain French monk returned from a visit to Jerusalem. He became known as Peter the Hermit. Of small stature and almost fragile frame, his glowing spirit of determination was apparent to all who beheld him. It was his mission, he believed, to bring the Holy City into Christian hands. He travelled all over Europe, barefooted, clad in an old woollen tunic and serge cloak; living on what he could find by the wayside and what was given him; and he roused the indignation of the whole of Europe over the need to free Jerusalem from the infidel.

It happened that in the year 1095 Pope Urban II was at Clermont in Auvergne presiding over a gathering of archbishops, bishops, abbots and other members of the clergy. People from all over Europe had come to hear him speak; Urban had been very impressed by the mission which Peter the Hermit had been carrying out and asked him to come to him. On the steps of the church, in the presence of the Pope, Peter told the assembly of the fate meted out to Christians in the Holy Land by the ruthless infidels who were eager to eliminate Christianity.

Peter, his dedication burning fiercely for now he saw the fulfilment of his dream, talked of the insults heaped on Christians, of the hideous deaths they were made to suffer and that he believed God had inspired him with a mission which was to bring back Jerusalem to Christianity.

The crowd was silent for a few seconds after he had finished speaking and then broke into loud cries of ‘Save Jerusalem. Save the Holy Land.’

Then Pope Urban raised his hand to ask for silence.

‘That royal city,’ he said, ‘which the Redeemer of the human race honoured and made illustrious by his coming and hallowed by his passion, demands deliverance. It looks to you, men of France, men from beyond the mountains, nations chosen and beloved by God, you the heirs of Charlemagne, from you, above all, Jerusalem asks for help. God will give glory to your arms. Take then the road to Jerusalem for the remission of your sins, and depart assured of the imperishable glory which awaits you in the Kingdom of Heaven.’

Again that hushed silence; then from a thousand throats there had risen the cry: ‘God wills it.’

‘Aye,’ the Pope had cried, ‘God wills it. If God was not in your souls you would not have answered as one man thus. Let this be your battle cry as you go forth against the Infidel. “God wills it.”’

The air had been filled with people’s shouting as with one voice: ‘God wills it.’

The Pope had held up his hands for silence.

‘Whosoever has a wish to enter in this pilgrimage, must wear upon his crown or on his chest the cross of the Lord.’

Peter the Hermit watched with glowing eyes. His mission was accomplished. The crusades had begun.

Since that memorable occasion there had been many a battle between Christians and Mussulmans; and it was at this time, when Louis was so troubled by his conscience and could not get the cries from Vitry-the-Burned out of his mind, and the Queen had realised that her vitality was being frustrated, that there was a great revival of anger against the Mussulmans and a desire to win back Jerusalem to Christianity.

Bernard of Clairvaux was deeply concerned by what was happening in Jerusalem. He came to the King and talked with him.

‘Here is a sorry state of affairs,’ he said. ‘God will be both sorrowful and angry. It is many years since the first crusade and we are no nearer to our purpose. Atrocities are being committed on our pilgrims. It is time the Christian world revolted against its enemies.’

Louis was immediately interested. He was burdened with sin; he longed to expiate those sins and to have an opportunity to show his repentance.

Bernard nodded. ‘Vitry-the-Burned hangs heavy on your conscience, my lord. It should never have happened. There should never have been a campaign against Theobald of Champagne.’

‘I know it now.’

‘In the first place,’ said Bernard, who was determined not to let the King escape lightly, ‘you should not have opposed Pierre de la Chatre. You should have recognised the authority of the Pope.’

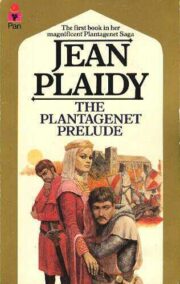

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.