Born in England in 1785, Mary moved to Meadville, Pennsylvania, when she was four years of age. Reportedly, she came from a strongly religious family, and she was often described as melancholy and shy. No incidents occurred until Mary turned nineteen. Then, for six weeks, she became deaf and blind. Three months later, she awoke from an extended overnight sleep (some eighteen to twenty hours) to know nothing of her surroundings or her previous life. However, within a few weeks, she could again read, do calculations, and write, although it was said that her penmanship had changed dramatically. This “new Mary” was described as “boisterous” and “fond of company,” as well as being a “nature lover.” After five weeks of this alter, she took another long sleep, awakening to her former self and possessing no knowledge of the person she had been. This altering back and forth between the melancholy Mary and the mirthful Mary continued until Reynolds was in her mid thirties. Then, the alterations stopped, and Reynolds became the “alter” personality until her death at age sixty-one.

Did is sometimes referred to as “a child’s post-traumatic stress syndrome.” Severe discipline, sexual abuse, or traumatic confrontations with death or the unexplained can manifest itself into individuals who retreat into an “alter personality,” one who can either absorb or deal with the trauma.

Hopefully, with better screening and diagnostic instruments, the future will bring continued growth and understanding to the treatment of this disorder. DSM-III’s creation of a separate category for the dissociative disorders gave legitimacy for the condition. A number of landmark publications in the 1980s devoted special issues to a discussion of multiple personalities. In 1994, DSM-IV set a primary criterion, which a patient must meet to be diagnosed with DID. Increased interest in the field remains strong, and distinguishing DID from other psychological illnesses remains the goal.

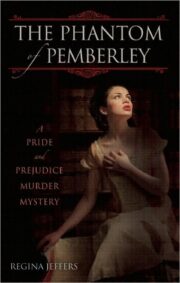

"The Phantom of Pemberley: A Pride and Prejudice Murder Mystery" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Phantom of Pemberley: A Pride and Prejudice Murder Mystery". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Phantom of Pemberley: A Pride and Prejudice Murder Mystery" друзьям в соцсетях.