Bunker soldiers—what’s left of them—are leaping over ammunition boxes in a frenzied game of stuffing a camera down their pants to take pictures of their genitals.

Lieutenant Kulker weeps in front of me. He will miss polishing all our furniture, the simple remains of a great Berlin. He’s an old soldier and when I first gave him instructions to polish Adi’s map table, he took off his jacket and threw it against the table legs. When a soldier does that, the furniture is his. “I’ll be of great help to you,” he told me that day, “as polish is always up to little tricks.”

“Lieutenant Kulker, we need another sentry at the top. We all perform our duties to the end. That’s an order.”

With a respectful salute, Lieutenant Kulker slowly climbs the iron stairs. When he’s out of sight, I take another lingering look at my home, this Bunker that will remain after us.

But there has to be a final inspection. I quickly run up the green slime steps, slipping and sliding. Kulker and two men sit lazily on the ground, their army kits beside them. Maybe they plan to flee. I have to let them know they’re still under orders. “You men must wash your feet and wear clean socks each day, bitte.”

They don’t answer. I know they plan to desert. Mess kits and spare clothing are tied in a bundle beside them.

Anger builds within me. I give it rein, letting it carry me into a wild uncontrollable rage. “You can’t desert your country. You must fight to the end. Your Führer went months eating only rice, He with his mountain climbing chest swelling in the uniform of an artist, avoiding ham sparkling in red blood, no companion but hunger. He ate dry bread on a bench in the Schonbrunn, digesting the sunshine into His empty stomach. For three Kronen a week, He had a bed and cabbage soup gaining cabbage logic. He painted broth into reality, sketched bread letting it escape from its own imagination. Holding His paintbrush like a torch, He marched proudly with factory workers, shoemakers, and bricklayers. The Führer understands conflict because He’s the center of life. By virtue of providence, He was thrown into a world struggle. There are rats that creep out in the last days of war. Das Volk steht auf, der Sturm bricht los!”

As the men stare at me silently, their faces show no emotion, and I go back down into the Bunker.

What is it like to die? Egyptian noblewomen, Goebbels said, were allowed to soften for days so that the embalmers would not find them beautiful. That will not be my worry. After Adi and I are truly joined in our marriage bed, after I take the capsule, my ovaries will ascend to the stars in a triumph of smoke. My death will be wanton before the flames, my bones stiffening in a blaze of elation—drunk on darkness. Will Adi’s supreme cadaver cooperate with the fire?

How lucky I am. There has never been a noble death in my family. Most relatives have died of gout and drooling senility, a few from uninspiring accidents. Everything I have is within Him now as we dream new dreams together. Afterward, we’ll have an enduring destiny.

The enemy, Adi assures me, have their terrible losses.

My Adi lies in bed, undressed and no longer timid about appearing naked, his mind still vivid and bright, that hidden masterpiece behind his forehead. Finally at rest, he’s Wagner lying on a sofa as Tristan, waiting beyond words or gestures or musical instruments in the helpless love for Isolde. I look down on Adi in the dark. As His body curls in a question mark, I place my hand on His head. For love of this man, I accept my fate. This is my gift, Vorsehung, providence. A little pillbox by the bed.

Yes, yes. I accept everything. I believe in His heart that includes all the bombs above and all the death and brokenness. I hold to His vision as those wildflowers at the Berghof hold to the earth. Without Him, I would die stupid.

“Louis IV said on the day he died, ‘Quand j’étais roi. When I was king.’”

“That was a silly Frenchman. You’re still the Führer. Now… say… I love you,” I urge.

“You know how I feel, my little soup-soul.”

“I want you to tell me.” I have a conjugal firmness in my voice.

“I married you didn’t I, sweet Evchen?”

He reaches for my arm, but I pull away. He lifts up on his side and looks down at me, surprised. Slowly he smiles. “I’m going to put you in for a decoration.”

But I don’t smile back.

Silence. Then he puts his fingers to his lips and moves them as he did Blondi’s lips when he wanted her to talk. “I… love… you.”

HE LOVES ME!

I do everything Magda says. Placing the worker’s cap over my hair, I sweat and rub the smell of Magda’s men between my legs, here in my Bierstuben, this smoky little cave just for him. I yodel, loud and clear, my mountain farmer’s voice of lushness and wildness that will define me.

All the following I have written so it lives forever on these pages:

My V-Volk is tossed against the wall now useless. He sniffs smelling Magda’s men and my worker’s sweat. His rutted beak, ruby red, striated, is bulging. With my factory hat still hiding my hair, I lean slowly over Him. Spending time with His fingers—he uses ALL of them (no longer needing to save his right ones for shaking hands)—he moistens his palms from the concrete walls to prepare my cleft, that tail of my heart, slithering in, sloughing. My blood increases by His probing. He expands, a slow steady slog, loamy, muzzy. He’s opening another map, this new road I have for Him, thrusting into a town, a field, a bridge. Swelling larger and larger, I think I’ll break. It’s dissection, being flayed, my earth frothing, abraiding. He’s my husband, guided by the heave of blood. Mein Gott. Ja! Ja! Everything begins to work inside, one strut after another in sickle movements, smooth ramparts of his hind part. His tip is Venice white, Munich cabbage pies slogging. Geli’s skin soaks me in formaldehyde. The smell of his mother’s illness. Blondi’s long canine uterus stretches me longer. Holding my organ in his hand, He divides skin flaps, frees up my ribs, strokes me, His giddy fingers deep, nicking away at my insulation, at my perfume of urine and stomach juices. I didn’t expect to feel so heavy, soaked with glorious connective tissues. He goes deeper into blood vessels more elegant than brocade, nerves and ducts like chiffon. I’m held within by the gravity of him as he loses his hands in my skin. Let it go, forget tender, forget. Ja… ja… ja… ja! Everywhere the back of His flinty tongue. Sehr beautiful. Ja. Sehr beautiful… ja… ja… osterblocken flowers roiled from His glans. Danka, danka… I love you, I love you I scream to my Adi who now lets me fill His eyes. My bulging under lips, faster… faster… shooting down stars in my satin purge. Me, opening his strength, racing to a gorge so glowing, phosphorous. I will shatter. Please shatter. I… am… splintering, light as spiders, breaching white peacocks, weedy, this Volkstrum agony. Nein, let me… nein, let me, let… me. Stilts of ecstasy as I bang, chug into myself, tearing apart the dark warmth of my brain.

We rise from the bed slowly, my body filled with soft ripples coming down from such exaltation. If we had time, I would press against him briefly. Being so charged, I could ignite us again. But this is selfish thinking. We have a stronger purpose, and he’s already begun to put on the common soldier’s uniform to place the Iron Cross on the left side of his tunic. He holds a picture of his mother tightly in his hand.

I put on the black dress with pink roses stitched near the neck, smooth the material down against my firm swimmer’s hips. I press a yellow tulip between my breasts.

He’s silent. It’s what Goebbels calls “Teutonic solemnity.” And I can only say Rilke’s words to comfort him:

Und wenn dich das Irdische vergass,

Zu dem stillen Erde sag: ich rinne.

Zu dem raschen Wasser sprich: Ich bin.

“And if the earth forgets us

tell the silent earth: I flow.

And to the rushing water say: I am.”

We arrange ourselves on Adi’s blue and white sofa where dots of blood linger from his piles. Soon more of his blood will crest the velvet. It’s early morning, but we only know that because of the small ticking clock on the table next to us. All the concrete blocks surrounding us seem closer than ever.

He’s brushing his hair with my “E.H.” brush, stroking so hard the bristles bend. When he holds the brush out to me, I drop it on the floor and calm down his hair with my hands.

Cyanide vials are held by his fingers so much shorter now. He’s withered wonderfully, thinned, relaxed. Wrinkles are gone from his face and he’s lost the unseen presence of conquest. Only his genius remains. He’s not what one will expect of a dead man. How beautiful will be the corpse of a man who doesn’t drink or smoke.

St. Perpetua, the strange saint we studied in school, was killed by a Roman pagan by guiding his sword to her throat. I put my hand on His and guide the capsule in his fingers to my lips.

We will die never knowing we are dead, side by side, a capsule soon on our tongues. We have only to bite down.

My notebook is on my lap, the pencil still in my hand. Adi is proud of me, proud that I’m happy to record each and every glorious moment till the end.

All I ever thought about down here, wished about, dreamed about was that I’d never be left behind. I hear the shells above. The Bunker shudders. The naked lights sway and flicker. Adi is beside me. When Bormann finally burns us, that trail of smoke we leave behind will be the “one long truth.”

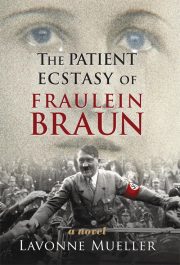

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.