Taking a handkerchief from my sleeve, I put it on Blondi’s head to mark a creature that truly loved him.

As I look in the mirror, I wonder how my face will change when I’m Frau Hitler? How will this wedding make my eyes look different? Though it will be a simple ceremony, I’m as excited as any bride.

Since the enemy’s advance guard is close, Adi leads me promptly to our wedding room. I take his arm above the elbow as I’ve seen so many women do when they walk with their husbands. When introduced to Walter Wagner, the city councilor greets me as “Mein Precious Eva.” Josef, Bormann and Magda are at our side. Götz Rupp stands in back of us wearing with devotion an army pompadour that makes him look like a sawed-off Hindenburg.

After Walter Wagner hears us declare that we’re third-generation Aryan, we’re united with a correctness and efficiency Adi loves. I start to sign the official paper “Eva Braun”—then laughingly correct myself to write “Eva Hitler” with pride. Bormann and Goebbels sign as witnesses before we walk to the dining area for the reception.

Magda whispers in my ear, “Thank you. Thank you,” as she displays the gold party badge the Führer took from his lapel to pin on her dress.

She doesn’t tell me what was said in her sacred five minutes with the Führer.

Bunker soldiers move in and out of the room, drinking syrupy champagne, congratulating us with gifts such as a statuette of Frederick the Great in white porcelain. Two captains practice their fencing techniques while chewing wedding cake.

Götz Rupp touches my arm, his hands engraved in dirt that comes from a scarcity of soap. “Mein Bride, I have most exciting news to deliver today at your wedding party.”

“What good news?” Adi asks hopefully.

“The pigeon was found in Prenzlauerberg.”

“Jupp?” I ask.

“Jupp delivered the Easter message to your mother, and I’ve sent him off with your wedding announcement. The Oberfeldwebel soared to the sky even though his wings are starting to rot.”

Adi was hoping for word of an Endsieg, a final victory however small.

Pushing herself between us, Magda tells Adi the children are asleep and now ready for us to view them.

On the way to the children’s room, Adi tells me what Magda requested in her five minutes alone with him.

“Something for her children?” I’m sarcastic, but since I’m now Frau Hitler, I have certain concessions.

“Helga.” Her name is said without emotion, as if she were someone he had never known.

“What about Helga?”

“She wants Helga to experience being a woman. Before she dies.”

So that was it. Adi should bed the girl in a glorious last living moment. I’m elated. My husband confides in me.

“I told Magda I’m no longer the husband of Germany,” Adi states.

“Though she bore Helga for you, that girl is no longer your concern.”

“Ein kind für den Führer! A child for the Führer! They all bore their children for me. Every German woman considered me her husband.”

“Helga should remain intact.”

“I told Magda you’d want it that way.”

Walking quickly ahead of me, Adi reaches the family room and stands beside Magda calmly. The six children are dressed in white nightgowns, a golden fan of hair on each pillow.

“Heidi has a bit of tonsillitis.” Magda takes a scarf from the drawer of an ink painted table by the bed, a table that was carefully transported from her country estate, a table that once cost three million Reichsmarks. As she tucks the elongated material around her child’s thin white neck, Heidi doesn’t move, so trusting in her sleep… not knowing she has to be watchful even in her bed.

“And Helga?” Adi moves to her side and stares down without emotion.

“As you can see, Mein Führer, I have loosened her hair. If you would only braid it this last time.”

“Magda, he has no time for that,” I say.

Adi stares silently at the sleeping Helga.

“They are so deeply under,” I whisper, looking at the children in one sweeping glance.

“This is a dress rehearsal. This is how it will look tomorrow. I’ve consulted Dr. Morell, Dr. Stumpfegger and Dr. Helmut Gustav Kunz agonizing over the final procedure for hours. The children were given a chocolate with Finodin. They’ll eagerly look forward to their more potent sweets tomorrow night, nicht? When they’re well into their merciful dreams, I’ll crush a cyanide capsule into each sweet little mouth.” Looking carefully at them one by one, she suddenly turns away. “Josef and I will follow. Father and mother will follow. Der Krieg ist aus. The war is over.” Scratches line her face where the children have fought against this dress rehearsal. “Josef and I keep our own cynide in a clean Upmann Havana cigar aluminum tube. We don’t trust a hollow tooth,” Magna says.

“Do not smoke or drink,” I order, my voice firm. “Leave in a tidy manner, as the Führer would wish it.”

“I’ll play one pure game of solitaire. Cards settle me.” Magda clutches at her blouse picking nervously at the sleeves. From my Bavarian lore, I realize this reflex action is known as “plucking”—the sign of a near and certain end.

How clever she is. I can never have his children. Never. If cards settle her, she’s played six aces. But I know that her little “aces” were helpful props Adi used for his health posters and family scenes. Like all good props after the run of a play, they’re discarded.

I see the children’s small inert faces as no more human than the concrete wall. “Remember what Frederick the Great said,” I announce, knowing this will please my husband. “‘No matter how important we may think such lives are in the events of the world, in the whole scheme of things, they are not significant.’”

Magda’s eyes bulge like pinches of clay sticking out from her pale face. “Frederick wasn’t a mother.”

“Death. That dark noun is masculine in the Teutonic languages but feminine in French,” Goebbels says softly as he reaches down and touches Helga’s head. “The French are right. Death is a girl.”

“The Earth will shake when we depart.” Goebbels adds.

Magda bends over the children crooning,

“Sleep, baby sleep

Die Sternlein sind die Lammerlein

Der Mond, der ist das Shäferlein

Away thou black dog fierce and wild

And do not harm my little child

Sleep, baby sleep

Schlaf, Kindlein, schlaf.”

Adi listens for only a moment, then abruptly leaves.

I return to my room and sit on the bed knowing he’s waiting for me. He is waiting for me.

Wearing one cyanide capsule each on leather strings around their necks, Magda and Josef are sleeping beside their children, Magda, no doubt, snoring softly with her bronze and silver Mother’s Cross at her throat. Bormann is restless on a cot in his office, prepared for the final duty to burn our bodies after death. The last of the guards protect the top bunker while sniffing powder made of dried syphilis scabs to make them immune to syphilis after the war. And I take a final look around this, my home, where I’m the official Hausfrau.

As I walk by the trunk that serves as a table, I wonder who had it before me. Maybe a woman who lives in Riedlingen with her grocer husband. Maybe actress Zara Leander kept costumes inside. Zara, the actress with beautiful Aryan thighs in silk stockings.

I feel a quickening in my breathing. Fear? No. I mustn’t fear death. Goebbels told me about the philosopher Kierkegaard and his ideas on anxiety. Fear is just the dizziness of freedom. Because I’m now free, I can resist looking down into an unknown abyss. And if I do look down, my spirit supports itself, that glorious spirit that is Adi.

So this is how it ends?

On a table in the dining area is a large brown mushroom once moist but now dry and brittle. Ribbentrop on a hiking expedition brought a bag of them to cure Adi’s piles. Giant mushrooms didn’t work. Adi sat on them for months.

Outside are the enemy planes that come night after night, so fast there’s little time for warning sirens.

My house. Sneezes and coughs hang invisibly in the Bunker for days along with stretches of dead air so close and stifling I can feel the earth inside my skin.

The guard at the foot of the stairs is gone. At one time, I could gauge to the second his mailed boot paces. It’s strange how many feelings one can have in between the steps from one wall to the other.

So this is how it looks at the end? No bored officers sitting at the table beating out tunes on their water glasses, no constant sound of the clicking of cartridge clips in pistols. Listless sentries sit topside by the entrance, restless on sturdy wooden classroom chairs with nothing to do but catch ants and creepers with sticky raisins and gossip about the Bunker people. On the floor: mess kits, dossiers, Red Cross toilet paper, broken cups, footlockers, balloon whisk, rusty nails, moldy boots, twisted canteens, python bones, a flare pistol, steel Düsseldorf pincers, flashlights, bits of wire, an empty tin for Zyclon B, half opened jar of stewed fruit with chunks of glass mixed in, a baby shoe, toilet brush propped up against the wall, rat droppings. Little Helmut Goebbels’ scooter from a toy store in Nuremberg is now upside-down. Twisted around an empty bottle of Hennessy cognac is a banner from an ambulance train. Button polish, Blondi’s water dish filled with cigarette butts, a pair of Zeiss field glasses, a gas mask, an open tin of Heinz tomato soup, and Magda’s reading pillow of stitched bluebirds with moveable beaks. Draped across an empty chair is a flag with lightning SS. My once beautiful wedding canapés, drooping and half eaten, are scattered on the white tablecloth stained with Rhine wine. Mattresses are stacked on the floor where once SS units slept and defended the Bunker. The cheese box that always frustrated Fräulein Manzialy when its top would cave in still stands dented inward as ever.

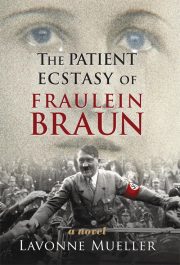

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.