“A Slav-Asiatic move, Major.” Magda arches under his weight. Flipping her over, he takes her from behind, scraping his cannibal teeth along her back.

“I can’t hold out much longer.” The major is obeying blindly, absolute and obedient, slewing hard and cutting all communications. There’s no lack in determination as he repeats his thrusts again and again, his soul indifferent to what’s beneath him. More formidable at the rear, he takes a series of very deliberate short pulls, putting his chest down heavily each time as Magda becomes a blur of teeth and hair. Then he blow-bursts through her highest command while they both yell as if poleaxed.

“Get to the front, Major,” Magda orders.

Turning over, she pulls him down so that he straddles the back of her hilly thighs. This is Magda’s end of the telescope. This is Magda’s offensive. Moving her rear up and down with incredible force, she lets the Major respond in only nominal ways. She forbids withdrawal and hammers a ruthless energy invading his reserves. The deeper they go, the deeper they lose rank, Magda becoming the infantry oberst. His incendiary unloads, squirting into her stronghold. Roaring together, they fall into ruin with a heaving rest.

They finish in fifteen minutes. Right on time. This is one more German victory.

The romp made her hairpiece and shoulder pads work loose and fall on the floor. Gallantly, the major picks one up, kissing it and tucking the glorious booty of a blissful skirmish in his pocket. Then he pats down his uniform tucking his genitals into the left pant leg telling her that he likes to “dress left.”

Finally, the major and I go up the iron stairs. He lingers behind to watch my slim legs. I ask him how the war is going. He answers, “Glanzend aber hoffnungslos.” Splendid but hopeless. We hurry through the emergency exit toward the garden of the Reich Chancellery. My shadow follows me out of the Bunker falling on the ruins of Berlin like a ghost in the brackish air. He tells me all about himself, how his mother regrets the loss of the monarchy no matter what he says to her. His wife wears silly braids that wind into huge earmuffs; she can’t be convinced to get a modern hair cut so he often thinks he’s better off having her as a sister. Maybe he’s going bald with all the hair that comes out in his comb. When he dines occasionally with the Führer, he goes hungry eating only awful raw carrots and tomatoes and has to dash home to devour his wife’s goulash. His father forgets to wear his party badge in his lapel.

“I have a law degree. So I’m outraged, Fräulein, to hear that General Fegelein was shot. Not because he was shot, of course. That was necessary. For we must not forget how Clemenceau dealt with internal traitors… rounding them up, having them shot to save France. General Fegelein was terminated without court of law first. Being an attorney, you must know what that means to me.”

All this rambling as we idle and curve in a Kubelwägen through the crumbled streets of Berlin that smell of chlorinated lime powder the soldiers use to cleanse the dead.

The major sees a Russian scout and fires, sending Ivan running behind a leaning wall. From a concealed pit, a gun rattles.

“Damn. They’re firing wild.” The major turns his head from side to side. “They’re using our knocked out tanks for shooting posts.” He pats the hand grenade stuck in his belt and then removes his Knight’s Cross hiding it in his pocket… wearing it makes him a desirable target. Twisting off the grenade’s porcelain knob, he throws it and the explosion silences the wild firing.

“You would do well to stop that scribbling, Fräulein. What can you be writing at a time like this?”

“All that I hear and see. In the world on these pages, I can be alone with the Führer.” I take a little theatrical pause to look around at the ruins. “Is it possible what they are saying… that the Leipzig Fair is still going on? Can that be true, Major?”

“Jawohl,” he replies proudly.

Smoking tracer rounds streak ahead. The flaming tail of a rocket salvo bursts over the truck in front of us, and it rears up taking a direct hit. Exhaust gases blow in my face.

“Get down,” the major yells. “They’ve got observation slots on the roofs. We have to keep moving. I can’t stop and get involved. I’m on an order that has to be obeyed.” He takes his helmet off and puts it on my head, pushing the strap still warm from his skin firmly under my chin.

Cinders fly into my mouth and my nose is running. The ground lurches under us. Two black crows perch on the warm plates of a tank. A soldier aims his weapon and fires a long burst at the birds and they fall to the ground beside a brown-uniformed Ivan with his head half gone.

“Yesterday I shot two Russians who were dressed in German uniforms. It was awful, Fräulein. How I hate these Ivans for their trickery. Firing into our own uniforms was so… so… monstrously upsetting.” The major is shaken in this memory, his voice strained, his eyes twitching.

War reins you in, yet it brings such nobility, I scribble in my memoir.

“First the Communists set our Reichstag on fire. Then the Allies set fire to Berlin. And to think I have an American stove in my house. My wife has grown attached to it and won’t let me haul it away.” Gripping the wheel of the car firmly, his large mouth moves vigorously as he chews gum with dedication. At each chew he puts his jaw to one side with the air of a gourmet.

“Major, please, I request you spit out the gum for patriotic purposes.” Everyone in Germany considers gum chewing an example of America’s degradation.

“Yes, you’re quite right. I forget as it keeps me steady, an awful habit I picked up when taking a course at Harvard. In the U.S.”

“You went to school in America?”

“Made the crossing on the steamer S.S. Hamburg. Took ten days. A beautiful trip. And before I left, I got such sound advice from Goebbels—expert advice that I carefully followed.”

“What did Josef tell you?”

“Go out for rowing. Row your guts out. Harvard loves that. And though my grades weren’t the best, I was a great success.”

The major becomes visibly pained by all the smoldering beams in our path. There’s no thought of Harvard anymore. “I have family that goes back many years. Under the Duke of Brunswick. Gunners—all of them.”

I tell the major I’ll be united to the Führer in just a few hours. “We’ll be married as a war couple.”

“I have the good fortune of helping retrieve your wedding dress.”

My wedding dress is itself patriotic since Renate wore it when her brother was decorated for bravery.

“And what will you wear in your wedding bed?” The major loosens his grip on the wheel and I think, So, even an officer whose cousin is a count wants to know what the Führer is like in bed.

“Major, don’t you find that rather classified?”

“I deal with the classified as a Golden pheasant.”

I don’t answer, for I’m stifled by the stench of death. The streets are stacked with bodies. What looks like heads and skulls are covered with silver and red powder drifting from the collapsing buildings.

Two heavy draft horses struggle to get up on bleeding legs. The major swerves to avoid hitting them.

“Don’t we treat wounded animals, Major? The Führer would not like leaving them like this.”

“Let me give you my scarf to use as a mask,” he says to change the subject.

“It’s necessary to see and smell what’s left. I won’t be turned away as a squeamish woman. Not when our badly wounded continue to fire back.”

“Good. You follow our no withdrawal policy.”

“Wouldn’t you expect that from the Führer’s future wife?” As I push my face as far as I can outside the window, smoke from a recently exploded artillery shell burns my nostrils. SS troops dug in beside an office building pop their heads up to salute.

“Look at that,” he says with irritation. “We’re forced to use old trucks with wood-burning gas generators.”

A little girl comes toward us holding a flower. Shells explode, and she makes what looks like a curtsey as blood oozes down her legs and covers her bulky pink socks. I want to stop and help her, but the major insists we keep going.

“My battalion adjutant has informed me that the Russians have our Lichtenstein bridge.”

“I’m quite aware of that, Major. I’m as informed as you are.”

“Look at these kids dressed like soldiers, closing their eyes when they shoot with old World War I rifles.” He yells: “Shoot low!”

“I think they’re rather endearing,” I say.

A baby lies in the street. We don’t see it in time and our vehicle runs over it without the slightest jolt.

“It was probably already dead,” the major says to calm me as I shut my eyes in anguish. “War is war. Schnapps is schnapps.” He sings: “O Susanna, oh weine nicht um mich, denn ich komm von Alabama…”

“Don’t sing that. It’s defeatist.” I cover my ears, fearful that the song will bring bad luck.

“Beneath an old lamplight… waiting… waiting… for my sweetheart…”

“Now that’s romantic,” I say.

“And are you waiting, Fräulein?”

“I’m Eva of the lamplight. But I won’t be waiting long.”

The ground trembles as pavement bricks bounce against the tires. Litter bearers draped in tent squares run to help a bleeding soldier in a drainage ditch.

A body flattened by a tank is enlarged nine or ten times its size, the gun enlarged, too, and it’s like the cartoon movies Goebbels likes so much.

“The Red Army is shooting every German officer they capture.”

“I don’t have to tell you what they do to German women, Major?” If he thinks he’s taking chances as an officer, I’m taking more chances as a woman.

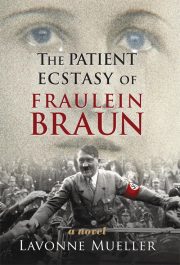

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.