“The inferiors. Those being studied while resettled.” I was thinking of my mother’s Jewish cook who made cakes from a hand-printed recipe book when I came home from school as a child.

“Discomfort is subjective and cancels out a definition.” Karl’s ring began to rotate slowly in the moist hollow under my right arm. Then he giggled. “They say Freud has a phobia about riding trains; he calls it Reisefieber. He should stay in Germany. Our trains for his kind are short in duration. One way.”

“What do you mean?” My voice was weak. I was feeling slow radiating pleasure from my armpit.

“Jews have no political concerns. Our major objective is order. The Führer is the world authority. He knows what’s best for us, even what is best for the Jews and gypsies without any help from diplomats and their shabby compromises. He’s our mathematician.”

Grinding his ring in my underarm moss, Karl suddenly yanked his hand away pulling out hairs so that my skin smarted and a jolt of warmth traveled to the tips of my fingers. I was abruptly moved along by the crowd, and Karl was lost. As I stared at the volumes being torched, his words made me proud.

A student pointed to Erich Kastner who was watching his books burn. Nobody was attempting to harm a hair on his body, so why was Kastner so stricken? Was it because that silly Heinrich Heine once said that a country that burns books will burn people? How ridiculous.

Holding out a flask, a buxom girl with a pustular rash on her face offered it to me. I held it over my mouth and sipped dripping Scotch without touching my lips to the rim, then handed the flask to the young man next to me as I felt a searing warmth reach my stomach.

Goebbels lit the pyre. “Proust,” he yelled, and tossed him in.

“Proust,” screamed students who threw one Proust after another into the fire, the pages losing detail in the wrinkles and shrivels of darkening soot. Goebbels held up a bag of madeleines. “Filthy French pastry,” he yelled, opening the bag and tossing the soft cookies into the fire.

A schoolboy wearing leggings, a brown shirt and red armband with swastika grabbed a madeleine and stuffed the cake between his legs. “Let Proust taste this.”

Everyone cheered. A sickening sweet scent suddenly floated up. (I remembered those burning madeleines when I later smelled the strange scorched sweetness of decaying bodies in bombed streets.)

Leather and oilskin covers were burning in red gold smoke, the many authors Goebbels always bragged about knowing. I no longer had to be intimidated by any titles.

Opinions and arguments withered in flames smooth and silk as liquid. Where did words go? This splendid fire was on our side as it writhed with a strange life of eddies and swirls. Fire, that symbol of the sun, was now billowing and glowing in the spines of so many unhealthy writers. Streaks of raging blue-red grew higher. Pages began to stir—alert and twisting as though in glowing agony. Inferior sentences stood out—bulging from the page and resisting their fate with a miracle of sparks glinting from below. Blistering heat burst the ink bellies turning what was left of so many idiot thoughts into shiny white ash, the sturdy bindings left behind like flat hot skulls.

A housewife reached beside the flames to salvage thick half-burned covers for her cooking fire. Stokers punched the fire with long black poles adding fuel and holding up book-skeletons before slamming them down.

With his Kriegsverdienstkreuz Medal at his neck, Bormann looked on calmly. He already existed in a world without books and liked to quote Adi who said surviving these awful authors forever was a great deliverance.

“Zola,” someone shouted, and many Zolas flew into the flames.

“Thomas Mann, H. G. Wells, Dos Passos, Einstein, Margaret Sanger,” called a girl behind me.

“Gide, Helen Keller, Freud,” chanted a tall thin boy with a pockmarked nose. He angled the books like boomerangs, sailing them into the fire.

“Brecht,” a young professor announced shoving the books forward with careful dignity. I saw Goebbels wince. He would have let Brecht remain in Berlin unharmed as he wasn’t a Jew (but his musical partner was). The Nazis could have used Brecht as some needed proof of literary renown, but Brecht had already fled to Zurich.

Students began to sing,

“Proust. Ach, Proust

We’ll burn you as we please

We’re in Berlin after all

Where things are done with ease

We’re in Berlin

We’re in Berlin

Where things are done with ease.”

As this was an important historic moment, I didn’t want to be left out. Finding Hemingway, I tossed him into the fire. Goebbels has a soft spot for Hemingway because of the author’s manly adventures and courageous fighting spirit, and I like some of his short stories that Goebbels gave me. Nevertheless, Hemingway was on the list. Certainly Adi did not approve of Hemingway hunting animals.

Next I picked up Magic Mountain and walked close to the flames. The professor next to me proudly stated: “Paper burns at 451 degrees Fahrenheit.” Feeling the blaze warm my cheeks, I pulled out pages, one by one saying: “Eins, zwei, drei… he loves me… loves me not… loves me… loves me not” I kept on, chapter by chapter, until “he loves me” was the final reward and the cover of the book curled in a radiant red glare. (Little did I know then that I’d see Berlin curling in ashes, street by street, like so many of these awful pages.)

I talk to Adi’s secretaries about those 20,000 books burning and how exciting it was, but they’re more interested in sharpening pencils on the Bunker’s concrete floor, eating gummy vanilla crescents that slur their speech, and drinking coffee made from acorns. They used to drink tea, but that’s now considered Anglo. These are Adi’s devoted women who adore and praise him and wear cut-down army field coats to show a military support in their workplace. They sit calmly at their desks alongside bicycle pumps and ration cards for bike tires. Their typewriters have extra large keys so the Führer can read the pages.

Women find him so attractive, so handsome. It surprises me that Adi thinks his face is too chubby. When he’s alone, he does these little exercises puffing out his skin as he thinks this will thin out his cheeks. With all his Austrian stature, he still believes he has a hunched profile. I assure him that his profile is very commanding. When speaking in public, he feels self-conscious though no one would ever guess that. He hunted endlessly for just the right back brace that would not be obvious under his suit. And he found a man who expertly designed a perfect one in a shop that was subsequently destroyed in the famous Reichkristallnacht. Having to be totally measured again by an Aryan who botched everything, Adi went back to wearing a tight belt under his shirt that was moderately helpful.

When the heavy tapping of their Remington keys stops, the conversation of the secretaries turns to love. These ordinary workingwomen want to ask me that one big question. You can see it in their eyes, how they study my face and scrutinize my clothes. What’s it like to make love to a genius?

Everyone wants a part of him and not just the women. At political rallies, most of the men in the audience have little black mustaches on their upper lips.

I have made love before Adi. I come from Bavaria. There are glorious men in Das Bayern. You have only to sit in the cafés to see that. But when I met Adi, other men were quickly forgotten. Adi is unique. He surprises not only his followers but also his lovers. Oh, he’s had lovers before me. One was that niece, Geli. I don’t know what the attraction was. You could hardly call her stylish. But Goebbels told me that Cleopatra married one of her brothers, and it’s thought by some she might have married another. Maybe a niece is going along those historic lines.

I don’t begrudge him former amours that are over… though I still fear the memory of Geli.

Adi was fond of Marlene Dietrich. She was often seen with theatrical Jews, but he believed she’d get over that. And her legs! They were luminous, smooth and perfect. In all the parades he reviewed, the legs of his young soldiers strutting and goose-stepping were her legs. He begged her to stay in Berlin, but she went to Hollywood and became an American citizen. When that happened, he was finally cured. The parade legs of his soldiers returned to him, wholesome and hairy.

Every morning I hope for good news about the war so Adi will once again enjoy those “hairy” parades. Looking for Fräulein Manzialy before she puts out the breakfast dumplings stuffed with cottage cheese, I ask her for a reading. She’s much more reliable than crude gypsies with bushy hair and uneducated ways. My mother always said that a person who cooks your food is close to a saint. Adi’s predictions are the most important, of course, but Fräulein Manzialy has sturdy common sense. She spreads cards on the table and pours us both what coffee she can make from walnuts and herbs. As she turns over the first card, I ask: “Will the Führer win his war?”

“No wonder we’re losing,” Fräulein Manzialy snaps at me. “Civilians talk about his war. It’s our war.”

“You’re quite right,” I say. “Will he win our war?”

Fräulein Manzialy answers, no matter what card is face up: “You live or you die.”

I want her to tell me that the cards say he was born at 6:22 in the morning by all the clocks in the house. A lucky time with lucky numbers. When he entered this life, his mother planted a tree and squeezed her breast milk on the roots. I want the cards to say he had a marvelous time in Klara’s womb and now will have a victorious time in this life, a last minute miracle like Frederick the Great. But Fräulein Manzialy only replies: “You live or you die.”

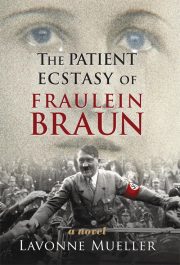

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.